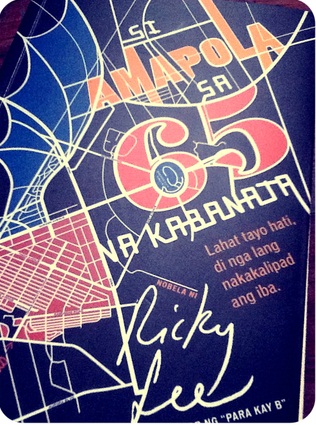

High drama and low humor in Ricky Lee’s new fiction about a cross-dressing ‘manananggal’

By Joel DavidThe results of the recently concluded American presidential elections seemed guaranteed to make everyone happy – except for the Republican Party and its now less-than-majority supporters.

American conservatives could have spared themselves their historic loss if they had taken the trouble to inspect the goings-on in a country their nation had once claimed for itself, the Republic of the Philippines. The admittedly oversimplified lesson that Philippine cultural experience demonstrates is: when conservative values seek to overwhelm a population too dispossessed to have anything to lose, the pushback has the potential to reach radical dimensions.

This is my way of assuring myself that a serendipitous sample, Ricky Lee’s recent novel “Si Amapola sa 65 na Kabanata” (Amapola in 65 Chapters), could only have emerged in a culture that had undergone Old-World colonization followed by successful American experimentations with colonial and neocolonial arrangements, enhanced by the installation of a banana republic-style dictatorship followed by a middle-force uprising, leaving the country utterly vulnerable to the dictates of globalization and unable to recover except by means of exporting its own labor force – which, as it turns out, proved to be an unexpectedly successful way of restoring some developmental sanguinity, some stable growth achieved via the continual trauma of surrendering its best and brightest to foreign masters.

“Si Amapola” is one of those rare works that will fulfill anyone who takes the effort to learn the language in which it is written. A serviceable translation might emerge sooner or later, but the novel’s impressive achievement in commingling a wide variety of so-called Filipino – from formal (Spanish-inflected) Tagalog to urban street slang to class-conscious (and occasionally hilariously broken) Taglish to fast-mutating gay lingo – will more than just provide a sampling of available linguistic options; it will convince the patriotically inclined that the national language in itself is at last capable of staking its claim as a major global literary medium. In practical terms, the message here is: if you know enough of the language to read casually, or enjoy reading aloud with friends or family, run out and get a copy of the book for the holidays.

The novels of Lee, only two of them so far, have revived intensive, even obsessive reading in the Philippines, selling in the tens of thousands (in a country where sales of a few hundreds would mark a title as a bestseller), with people claiming to have read them several times over and classrooms and offices spontaneously breaking into unplanned discussions of his fictions; lives get transformed as people assimilate his characters’ personalities, and Lee himself stated that a few couples have claimed to him that their acquaintance started with a mutual admiration of his work.

This is the type of response that, in the recent past, only movies could generate – and the connection may well have been preordained, since Lee had previously made his mark on the popular imagination as the country’s premier screenwriter. The difference between the written word and the filmed script, per Lee, is in the nature of the reader’s participation: film buffs (usually as fans of specific performers) would strive to approximate the costume, performance, and delivery of their preferred characters, while readers would assimilate a novel’s characters, interpreting them in new (literally novel) ways, sometimes providing background and future developments, and even shifting from one personage to another.

“Si Amapola” affords entire worlds for its readers to inhabit, functioning as the culmination of its author’s attempts to break every perceived boundary in art (and consequently in society) in its pursuit of truth and terror, pain and pleasure. For Lee, the process began with his last few major film scripts (notably for Lino Brocka’s multi-generic “Gumapang Ka sa Lusak” [Dirty Affair]) and first emerged in print with his comeback novellette “Kabilang sa mga Nawawala” (Among the Missing).

“Si Amapola,” more than his previous novel “Para Kay B (O Kung Paano Dinevastate ng Pag-ibig ang 4 out of 5 sa Atin)” (For B [Or How Love Devastated 4 Out of 5 of Us]), is a direct descendant of “Kabilang,” at that point the language’s definitive magic-realist narrative. Despite this stylistic connection “Si Amapola” is sui generis, impossible to track because of its fantastically extreme dimensions that abhor any notion of middle ground.

The contradictions begin with the title character, a queer cross-dressing performer who possesses two “alters”: Isaac, a macho man (complete with an understandably infatuated girlfriend), and Zaldy, a closeted yuppie. His mother, Nanay Angie, took him home after she found him separated from his baby sister and, notwithstanding the absence of blood relations and any familial connections, raised him (and his other personalities) with more love and acceptance than most children are able to receive from their own “normal” relatives. A policeman named Emil, a fan of real-life Philippine superstar Nora Aunor, then introduces Amapola to his Lola Sepa, a woman who had fallen in love with Andres Bonifacio, the true (also real-life) tragic hero of the 19th-century revolution against Spanish colonization. Lola Sepa moved through time, using a then-recent technology – the flush toilet – as her portal, surviving temporal and septic transitions simply because she, like her great-grandchild Amapola, happens to be a ‘manananggal,’ a self-segmenting viscera-sucking mythological creature.

Already these details suggest issues of identity and revolutionary history, high drama and low humor, cinematic immediacy and philosophical discourse, and a melange of popular genres that do not even bother to acknowledge their supposed mutual incompatibilities; if you can imagine, for example, that a pair of ‘manananggal’ lovers could be so abject and lustful as to engage in monstrous intercourse, you can expect that Lee will take you there. The novel’s interlacing with contemporary Philippine politics provides a ludic challenge for those familiar with recent events; those who would rather settle for a rollicking great time, willing to be fascinated, repulsed, amused, and emotionally walloped by an unmitigated passion for language, country, and the least and therefore the greatest among us, will be rewarded by flesh-and-blood (riven or otherwise) characters enacting a social drama too fantastic to be true, yet ultimately too true to be disavowed.

At the end of the wondrously self-contained narrative, you might be able to look up some related literature on the novel and read about Lee announcing a sequel. Pressed about this too-insistent meta-contradiction of how something that had already ended could manage to persist in an unendurable (because unpredictable) future time, he said: “Amapola the character exists in two parts. Why then can’t he have two lives?” Nevertheless my advice remains, this time as a warning: get the present book and do not wait for a two-in-one consumption. The pleasure, and the pain, might prove too much to bear by then.

Joel David is Associate Professor for Cultural Studies at Inha University in Incheon, Korea. He is the author of a number of books on Philippine cinema and was founding Director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute.