Bed-ridden speculations on national character: Filipinos as caregivers of the world

By Marian Pastor RocesI did not presume that you all would be interested, as a matter of course, in the emergency surgery I needed 11 days ago; after which I was confined to a pleasant enough room at Capitol Med in QC. Back home yesterday.

Still have the sutures, the discomfort in the belly, and the sagging skin from precipitous weight loss.

But I’m not my story this morning. Today I am gathering striking recollections of hospital hum through the haze of anaesthesia, pain killers, and magical antibiotics. Something important, uhm, coagulated in that blur. It is to do with national character.

Often spuriously invoked—invariably by the prism of pop psychology — this idea of a national character should alert our capacity for skepticism.

Then again.

Where I was, the nurses, medtechs, physical therapists, orderlies, doctors young and gnarled, why the janitors too, are all possessed of stunning dignity and polished skills. And a compassionate spirit that requires no narcissistic projection.

I’m regaining health quickly because of their calm expertise and sheer kindness.

Through my confinement, I had room in my head for recollections of Filipino medical practitioners with rare heart. I’ll tell you of just two, because I am certain that if you are Filipino, you would know many others.

My lolo, Dr. Juan Arceo Pastor, whom my lola said would come home near dawn, asleep on his horse, from curing the sick in the isolated barrios of the Batangas mountains. Penny Josephine Bundoc of Physicians for Peace – Philippines moving around places like Tawi-Tawi to literally give peace a chance. (It hence comes as no surprise that Penny is Jesse Robredo’s sister.)

This is a species of competence and heart that is unimaginable outside a larger community involved in the same cluster of disciplines, practiced in a culture-bound, consistent way. And, indeed, Filipino physicians and health workers are legendary, globally, for that rare fusion of expertise and a nearly unfathomable capacity for tending to the world’s sick and infirm.

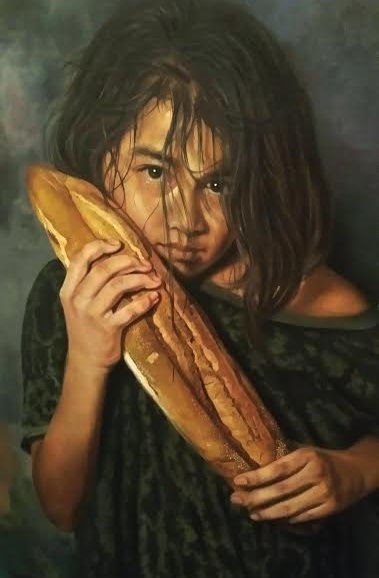

Too, beyond our empathetic and well-trained medical practitioners is the bigger demographic field of yayas deploying themselves universally — and with an impact we will begin to see clearly in the next decades.

It has been remarked that the youth of Hong Kong who waged a seemingly impossible contest with China’s authoritarian government, were raised by Filipino yayas.

This is observed often enough: Filipinos are the care-givers of the world.

And it is not so much the statistics of the matter as it is the quality of care that inspires confidence, in ourselves and among those we care for: that that care is unusually reliable and unusually kind.

This is ubiquity, consistency, and stability that ought to give us pause. Filipinos, who also figure prominently in international seafaring, seem to be bound together as a community of, well, healers. To use the appropriate word.

For all our cantankerousness and capacity for mischief and crime, Filipinos do have a shared culture of extraordinary care-giving, based on highly elaborated traditional and contemporary knowledge, on one hand, and on the other, an empathetic collective soul.

We belong to a community of adepts at the restoration of well-being. I hate it that this sounds New-Agey, but I daresay the claim will pass muster if challenged for intellectual rigor.

In any case, I write this because we do not see this Filipino-ness on Facebook, in the traditional media, and indeed in art. This compelling Filipino-ness is not palpable in the calculations of pundits; nor significantly evoked and recognized in the work of artists, politicians, social scientists.

But this is a Philippines that lives quietly through, and under, the din of our political life.

Were that our politicians and other analysts are more cognizant of Filipinos — more than as dots in a survey nor inept vox populi soundings in the media nor projections upon the majority of both Left and rightwing ambition — rather as creatures bound by a shared and well-expressed aptitude for curing and caring.

Deeper understanding of this Filipino-ness can only bode well in the struggle to build healthy institutions.

One more fleeting thought, post-surgery. An American ambassador once said to me. “Filipinos do not yet form well-configured political fronts in the US. But when, after surgery, Americans come out of anaesthesis, a Filipino face is what we want to see.”

Marian Pastor Roces is a Cultural Studies scholar, an institutional critic, and a curator. She founded and runs TAO INC, which is the Philippines’ only corporation that specializes in museum development. This essay originally appeared on Facebook and is being republished with permission.