Culinary pride, not prejudice (Part 2)

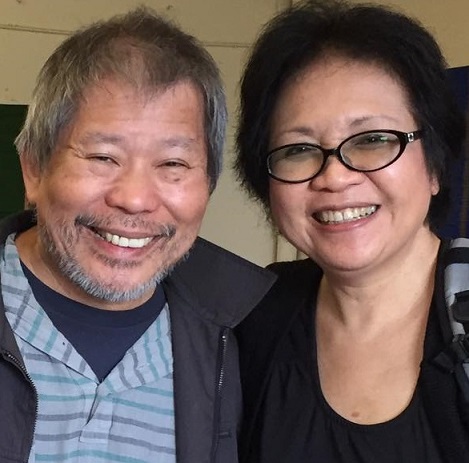

By Carina EvangelistaOn the subway ride to the restaurant, while I was coaxing Romy Dorotan to talk about childhood memories, I said I was curious about what memories he might have had around food as a child–say, if something had sated him so wonderfully after hunger. As we stuffed our faces with our sandwiches, he pondered the phenomenon of hunger–something he never felt growing up in the Philippines. He marveled at the fact that there were really ever only three meals a day [merienda was for the occasional weekend] but he does not remember ever feeling hungry. Growing up in the province, meals very rarely incorporated processed food. He notes that there was no such thing as fast food and he doesn’t recall ever snacking as an Accounting major at the University of the Philippines in Diliman. He was not acquainted with hunger until he migrated to the U.S. and it was not so much out of penury. He chalks it to being too busy that the habit of eating each meal on time was no longer daily.

On hunger, Romy points out that according to the late Doreen Fernandez, our street barbecue of chicken hearts, liver, feet, chicken or pork intestines, and coagulated chicken or pork blood–smoky from the charring from coal and the city smog, is a culinary byproduct of the Marcos years. There is nothing either literally or historically delicate about these delicacies. A nation plunged in debt with economic opportunity reserved only for the Marcoses and their cronies led to a wave of Philippine diaspora, seconding that of Carlos Bulosan’s generation. And street food vending became a viable source of income for those who could not find jobs either at home or elsewhere. Offal also became the affordable source of protein for many who could no longer buy the better portions of meat or poultry. And typical of Pinoys, nothing is fully cooked without humor. These parts that others would not ever think to eat are named IUD (intestines), Adidas (feet), or Betamax (bricks of blood).

The conversation we had while sampling his ‘Fish Pilidine’ [Fish Almondine served with chopped pili nuts instead of almonds] served with the roast potatoes and sunchokes circled around random topics such as his shift toward more Asian cooking when he was recruited to cook for a hotel in Key West. The availability of more tropical food produce signaled a return to dishes from home.

His epic fail in culinary adventurism was a quiche. At the height of the popularity of the Quiche Lorraine in the late 1970s, he decided to offer on the menu avocado quiche. This was decades before the triumph of the avocado gracing just about everything from toast to cocktail drinks. Not a single order for the quiche was made. And his temper as a chef was tempered by a bird. Throwing a hissy fit in the kitchen one day, he decided to up and leave in the middle of the day. As soon as he stepped out the door never to return, a bird releases from its cloaca a generous helping of crap that landed squarely on Romy who promptly looked up to acknowledge the cosmos calling him on his diva behavior as he pivoted back to his station of art and heart in the kitchen.

Philippine food is enjoying the limelight right now. We revisited a debate sparked by a theory for why it has taken this long for mainstream America to embrace Philippine food. Using a colonial trope, the notion of ‘hiya’ or culturally inflected shame was an explanation once offered.

Cooking is alchemy: the blending of ingredients, spices, oils; the melding of time, water, sun, earth, and memory. Sharing meals is also alchemy: the meeting of minds, hearts, and appetites. Food is a culmination: of sowing, cultivating, breeding, harvesting, bundling, fishing, butchering, weighing, selling, buying, washing, chopping, stirring, curing, searing, roasting, steaming, baking, plating, and savoring. It’s about hunger, nourishment, and delectation. It is flavor, aroma, and texture with varying levels of simple and complex, rich and pure, subtle and intense. Food is time. Knowledge of, and attitudes toward, eating and cooking are passed down through generations like DNA and heirloom. It is mystery. Knowledge of, and attitudes toward, eating and cooking are discovered through travel (whether of people or of food); shaped by other cultures; serendipitously produced because birds are razing coffee plantations; even borne of strife fashioned as the self-possessed vestiges of survival such as IUD, Adidas, and Betamax. We mine our memories and treasure our traditions; stoke our imagination and pleasure what is possible.

The Ilocanos feed their babies honey and ampalaya so that the child’s palate and mind would be awakened to the sweet and the bitter in food and in life. Food is instructive. Food is comfort. More than any of the action words associated with food, think of these two verbs: serve and share. Breaking bread with others creates kinship. Filipinos greet each other not with “How are you?” but with “Have you eaten?” We instinctively enjoin others—even strangers—to partake of our food no matter how humble the fare or the absence of silverware: “Kain tayo. [Let’s eat.]” So the idea that we are ashamed of our food from internalized colonial mentality is un-Filipino baloney.

Filipinos who live abroad wonder why Filipino restaurants in their adopted countries do not proliferate as much as Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, or Thai restaurants. Another theory posited the lack of distinction of a cuisine perceived to be mere copies of Spanish or Chinese dishes. I prefer this theory: Our cultural attitude toward food is from the fiesta—all the dishes are laid out on the table and everyone goes around anytime s/he wants, as often as s/he wants. No seating arrangements. No fussy place settings with knives and forks or fancy linens. People gather around the food to eat of course but more definitely to commune. And they stay forever because they don’t run out of stories to share, jokes to crack, songs to belt out on the karaoke, people both present and absent to tease, politics to debate, gossip to spread, sorrows to share, and the next salu-salo to plan. Diasporic Filipinos work extremely hard so that next gathering that comes around only when folks are not working long hours is one to stretch day into night. Going to a restaurant precludes staying forever.

Tell me what you eat, and I’ll tell you who you are.

–Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Well, rice–for which some 200 words have been identified among Philippine languages and dialects–and laughter are the basic ingredients in Pinoy meals. And no, you can’t quite order laughter from the toniest restaurants in the world. Sa mga karinderya, kahit na anong ulam sa maliit na mangkok, sampung piso ang kanin at libre ang tawanan. [In the cheapest eateries, whatever viand is in the small bowl, rice is ten pesos ($0.20) and laughter is free.]

What I thought would be an hour interview with Romy morphed into a day of memories and of memorable food. I only regret not having found my way back shortly after that visit to taste the kesong puti ice cream he was going to make with the water buffalo milk we bought at the Union Square Farmers’ Market but it will just be something to look forward to on a future visit. All told, my perpetual hunger for enlightenment was sated and I left Purple Yam in a condition that can only be adequately described with the Filipino expressions busog ang diwa [spirit is full] and mataba ang puso [with fattened heart].

Part 1: A day in the kitchen of Romy Dorotan

Carina Evangelista is currently Editor at Artifex Press in New York. She has also worked on numerous exhibitions and catalogues at the Museum of Modern Art. She is contributing author to a number of publications on Philippine contemporary art. She wrote the libretto for the musical Manhid, staged by Ballet Philippines; served as actor and lyricist for the film Pisay; and early this year participated as visual artist in Open City, the first Manila Biennale held in Intramuros.