A day in the kitchen of Romy Dorotan (Part 1)

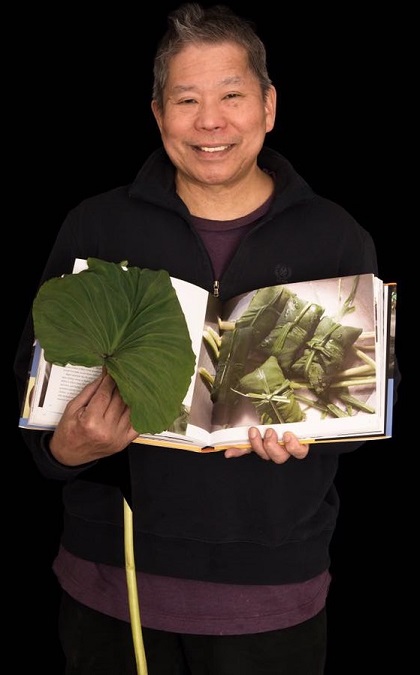

Dorotan’s portrait at the ongoing exhibition, ‘New Immigrants: What Gifts We Bring.’ He is shown beaming with a taro leaf in his hand. Laing, taro leaves cooked with garlic, onion, and chili in coconut milk, is the quintessential Bicolano dish. Photo by Tom Pich

On a beautiful Spring morning, I met Chef Romy Dorotan at the Union Square farmers’ market to do some food shopping before heading to Purple Yam Brooklyn for what he called a session of ‘satsatan lang.’ My husband James and I have known Romy and his wife Amy Besa, the duo behind Cendrillon in Soho then and Purple Yam for more than a decade now.

“When did food first lodge itself in your consciousness?” I asked in the spirit of their book, Memories of Philippine Kitchens, in which Amy captures the moment of her “first inkling of the power of food” when roosters crowed before daybreak as pan de sal was brought into the kitchen. Although he initially seemed to prefer avoiding a philosophical or a romanticized discussion of food that is perchance best left to speak for itself, Romy indulged my question. We went down the steps to the kitchen in the basement of Purple Yam Brooklyn and down his memory lane while he moved from sink to counter to walk-in cooler to stove to oven.

Like Amy, Romy’s first memory of food was pan de sal. He remembers early mornings in Irosin, Sorsogon. Pan de sal is set for breakfast; coffee for adults and for the children, “kape de arroz”–a caffeine-free drink made with uncooked rice roasted first then steeped in hot water. So, for the couple–as for many Filipinos, the Proustian madeleine is the small crusty ‘bread of salt’; it’s no surprise that among the first recipes in their cookbook is Ube Pan de Sal.

Romy was born to a father who migrated to the Philippines from mainland China, marrying a local lass and raising his family to grow into the fabric of Bicolano culture, and a mother who was a merchant, selling staples like rice, sardines, and cooking oil in the market. The figure memorable to him in the kitchen was a Chinese cook hired during special occasions. Standing before coal-fired stoves in her loose white sando, swigging from a bottle of sioktong, she prepared fiesta meals. Romy cited arroz valenciana, fish escabeche, and camaron rebosado among the dishes that our Chinese immigrant ascendants improvised. Incorporating Spanish elements in traditionally Chinese dishes popularized their cooking. Hybridization is after all Philippinization. Dorotan is itself a Filipinized Chinese name.

Romy started his duck adobo upon our arrival at Purple Yam. Mulberry vinegar, fresh bay leaves and bird chilies, and garlic go into the pot. I taste the vinegar as he reveals its provenance. Besieged by birds that raided the coffee trees in a plantation in Bukidnon, the owner decided to plant mulberry among the coffee. Problem solved. Mulberry aplenty for birds and for fermentation into vinegar that’s so good I imagine macerating figs in it.

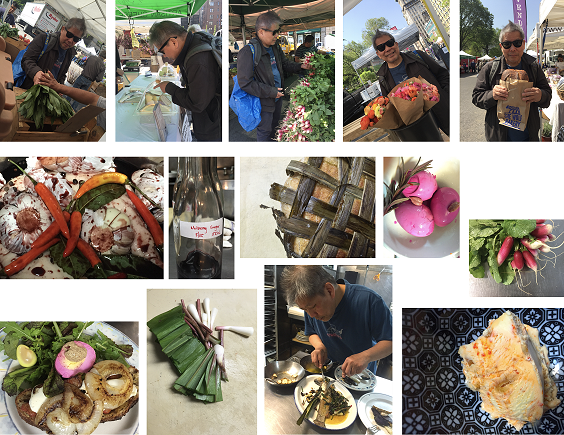

A conversation that began at the Union Square farmers’ market and continued all the way to the kitchen basement of Purple Yam Brooklyn. Photos by Carina Evangelista

As the adobo simmered, he prepares our brunch, fishing boiled duck eggs from their sumptuous magenta bath of beet juice, rosemary, and cardamom, then quail eggs from their earthy bath of mulberry vinegar, chili flakes, and turmeric oil. He unwraps the sourdough boule that he and Perry Mamaril had baked the night before. Perry, an artist who also cooks at Purple Yam, created a pandan leaf lattice for the bread. Romy holds up the cross-sections of their bread and of the polenta boule we bought at the farmers’ market, showing the difference in distribution of air pockets. “Ours is not there yet. It takes years and years to achieve this level of perfection,” states the seasoned cook who sees his craft as one of perpetual discovery, learning, and honing.

We try both breads with the cheeses and radishes we bought. Then, he cuts thicker slices of bread, fries up some tocino, rings of cipollini onions, and builds open faced sandwiches topped with fresh mozzarella.

After finishing the tosoulog–tocino, sourdough bread, duck and quail eggs, Romy throws purple fingerling potatoes and Jerusalem artichokes doused with extra virgin olive oil into the oven. What brought him to the U.S.? A scholarship to pursue a doctorate in Economics at Temple University where he would later meet Amy. A sister prodded him to study abroad. He was not seeking greener pastures but had he not left, he would have followed an older brother in his footsteps as a cadre leader killed during the Marcos dictatorship. “I’d probably be dead, too, now.”

Personal and national histories intertwine. How could Romy’s journey from a family grieving a brother’s early death alloyed with anger at an abusive regime lead to the kitchen? The activist left but did not leave his activism behind. Amy who wrote in her introduction to their cookbook, “I said my farewell to a country that had shaped my soul and to a people that had wounded my heart,” was also at Temple pursuing a master’s in mass communication. They met in the KDP (Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino), protesting discrimination against Filipinos in the U.S. and calling for an end to U.S. intervention that empowered Philippine Martial Law.

They survived with odd jobs. Amy worked in a restaurant cooking pastry and Romy started out as a dishwasher at The Frog, a French bistro in Philadelphia. One day, the chef suddenly left for another restaurant, taking with him all the cooks. Romy was suddenly promoted to cooking staff meals. Later, Amy was already teaching at Temple but a KDP call prompted a move to New York. Romy expanded his culinary repertoire as lunch chef at Hubert’s. The artist in the activist was woke in the city that is the world’s food mecca; and the rest is history.

Romy pairs the potatoes and sunchokes with his version of Fish Almondine, fried brook trout with a sauce made with butter, garlic, ramps, and chopped pili nuts. We had just had two lunches in a row but he offers three flavors of ice cream: Malagos chocolate with rhubarb and strawberry, mulberry with pomelo rind, and goji berry with longan.

Purple Yam is more than a restaurant. Amy has been hailed the “universally acknowledged den mother of Asian chefs in America” for her inclusivity, inviting innovative Asian chefs to guest at their restaurants. Their restaurants have also been known to provide wall space for art. You plop down in one of their booths and by the time you get up, you had been sitting there for hours being plied with damn good food and banter. You actually want to stay forever. Neither Romy nor I could that day but he did not let me leave without my precious duck adobo.

Romy Dorotan is among the luminaries celebrated in the currently running exhibition, New Immigrants: What Gifts We Bring, at the Lower East Side gallery of City Lore (The New York Center for Urban Culture).

Carina Evangelista is currently Editor at Artifex Press in New York. She has also worked on numerous exhibitions and catalogues at the Museum of Modern Art. She is contributing author to a number of publications on Philippine contemporary art. She wrote the libretto for the musical Manhid, staged by Ballet Philippines; served as actor and lyricist for the film Pisay; and early this year participated as visual artist in Open City, the first Manila Biennale held in Intramuros.

NEXT: Culinary pride not prejudice