Where are the feel-good migration stories?

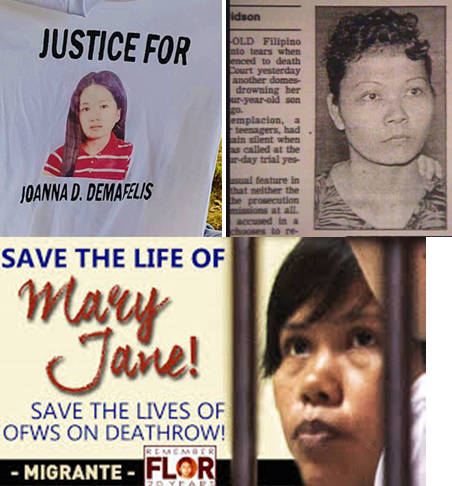

• Joanna Demafelis, Kuwait, 2018 (killed allegedly by employers)

• Flor Contemplacion, Singapore, 1995 (executed)

• Mary Jane Veloso, Indonesia, 2010 (on death row)

By Jeremaiah M. Opiniano

Remittances have been the reason for overseas Filipinos’ symbolic tag as heroes since a formal labor export program began in 1974.

From the 1970s to the mid-2000s, remittances have helped shore up the homeland economy’s fiscal issues, mitigated the impacts of domestic unemployment, and somewhat help buoy the Philippines’ gross national product. That period, spanning just over three decades, saw the Philippines’ macro-economic growth performance as “boom and bust” —like a roller coaster, going up and down. Meanwhile, there is rising overseas migration (including that for overseas permanent residency, depending on the migration pathways countries offer to foreigners) and a concomitant rise of labor, welfare, human rights and criminal / civil cases affecting Filipinos in various host lands. So with rising migration and remittances is a perceived growing number of problems facing Filipinos abroad, and the corollary family-level social costs.

However, there is a change in the plot: since the 2008 global economic crisis, the Philippine economy is now one of the top economic performers in the world. Sustained gross domestic product growth, with an annual average of some 6 percent, these past 10 years is slowly buoying the Philippine economy. Coinciding that is what some demographers perceive to be a demographic transition, where old and young dependents are lesser and the working force is bulging in numbers. That situation gives the Philippines a chance —a 30-year window, says some demographic projections — to drum up as many savings and investments and have these parked at home. Overseas migration and remittances have been contributing their share to this ongoing demographic transition, currently through buoying local consumption.

Yet one wonders why the stories are still the same sordid ones? The diplomatic standoff with Kuwait following the gruesome death of domestic worker Joanna Demafelis has been hogging the news for months.

For decades now, Filipino women are still viewed as seeking dates online, underpaid domestic workers, or abused spouses even after they got permanent residency.

Filipinos are also viewed as workers with a caring attitude who can endure tough conditions just to earn more and please employers; as the behaved foreigners.

Yet what is baffling is that the storylines of the Filipino migration saga are still perceived to be the same even in the age of social media. Filipinos abroad being lured by Philippine real property companies is so 2000s. The sending of balikbayan boxes is already a generation old.

Filipinos’ overseas migration has already brought about socio-cultural, economic and institutional changes in Philippine society, sociologist and historian Filomeno Aguilar, Jr. writes in his anthology “The Migration Revolution” (2014). Class structures have been reconfigured. That is the current scene of the Filipino migration phenomenon.

Given the current era of a Philippine economy that’s in a demographic transition which runs side-by-side with overseas migration, what can be the new Philippine future beside the exodus? Can new stories about Filipinos abroad be told instead of sticking to usual tales?

Will Filipino food, for example, be mainstreamed in host societies and capture the imagination of nostalgic and curious foreign taste buds? With social media easily bridging transnational Filipino families, what kinds of family rearing tales have we not heard from those who endured parental separation and found successes? In some Filipino rural communities, kinship and community embeddedness mitigate the risks of migration’s family-level social costs. With Japan having a long history of Filipinas going there as entertainers, and that migration pathway stopped over a decade ago, have the Japanese of today looked at Filipinos differently?

How many more Filipinos will become elected leaders in countries, like the United States, New Zealand, Korea or Canada?

There can be a myriad of good and bad tales about the overseas Filipino. People aspire for more pleasant stories, especially since Filipinos are known for extending their personal boundaries and fits of empathy. Filipinos also aspire for less of the tear-jerking stories —from abused domestic workers to Filipino permanent residents who are duping compatriots on temporary work visas. With Filipinos abroad now an influential force for their motherland, and them being exposed to better systems abroad, how can gruesome migration tales be changed for the better?

Jeremaiah Opiniano is a doctoral student (geography) at The University of Adelaide in Australia. He also handles a nonprofit research group on migration and development issues in the Philippines: The Institute for Migration and Development Issues (IMDI). He can be reached at ofw_philanthropy@yahoo.com.

(C) The FilAm 2018