IN THE MOTHERLAND: Some notes to folks who’ve encountered my attempts at Tagalog

By Laurel Fantauzzo

To Ate Susan, My First Tagalog Teacher: I’m sorry I said, “Mabaho ang anak mo!” I meant to say your daughter is tall. Instead I said she was stinky. Your daughter is not stinky. Again, I am sorry.

To My Very Confused New Filipino Friend: I’m sorry I said, “Ipis ako!”I meant to say, “I’m thinking!” Not, “I’m cockroach!”

To the Young Curator in Makati Wearing a Bespoke Suit: I’m sorry I responded, “Opo,” when you asked me in English, “Are you a student, madame?” You seemed very displeased when I said “Opo.” Of all the Tagalog I attempt, “Opo” is one phrase I can pronounce correctly, and before I said it to you, I was silently glad my respect for strangers here is so easy and automatic. One two-syllable phrase to encompass “Yes ma’am/sir.”

But when I said “Opo,” I felt your disapproval cloud the air between us. For the next two minutes we spent together, you did not look at my face again. You looked down and tightened your mouth. I remembered what some Filipino academics have murmured to me: that English is the language of business in the Philippines. That Tagalog is sometimes regarded as a lower language, for friends and family only, not for formal occasions. That some Filipinos of a certain class will refuse to use Tagalog entirely, especially during a transaction with an obvious American.

I could feel your unspoken indignance, young curator. But I didn’t mean to insult you. I meant to respect you. When I sensed your disapproval, I tucked my Tagalog away, and my English, too, and that’s why I bought my ticket in silence.

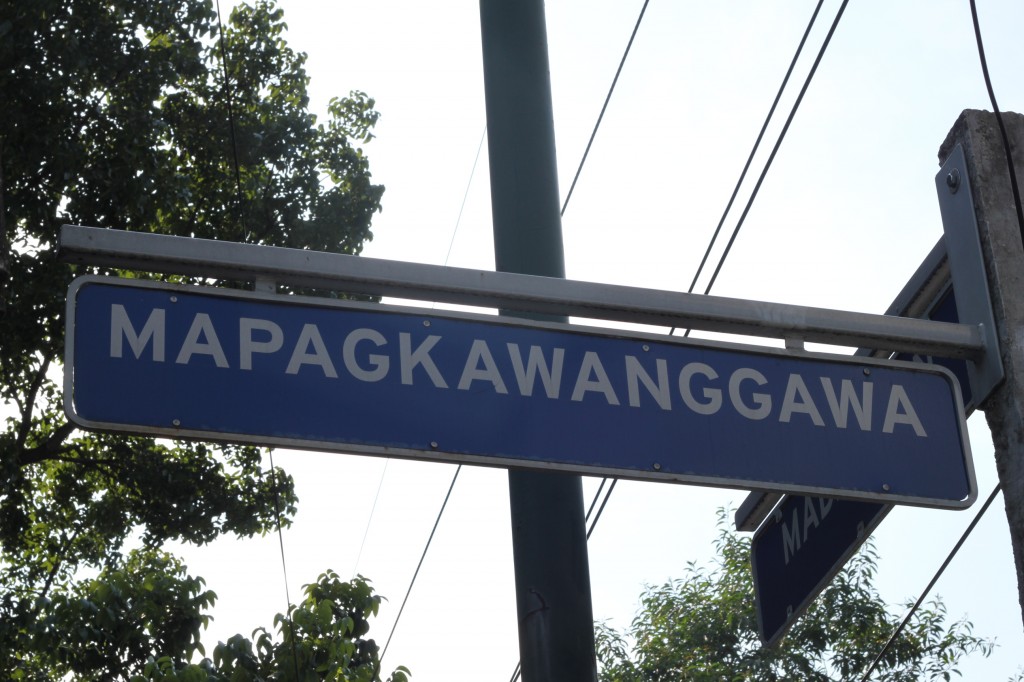

To This Particular Street Sign: I did my best to read you out loud on my own. But it took four separate native Tagalog speakers for me to complete your name out loud even once. I’m sorry.

To the Older Acquaintance Who Demanded to Know Why My Mother Never Taught Me Tagalog, and Why Couldn’t I Speak Tagalog As Well as the Adorable Little Australian Girl on Youtube Singing the Bahay Kubo Song?: I replied to you in the simplest way possible; “Ayaw niya.” My mother didn’t like to. This made you laugh. It was probably my pronunciation; my pronunciation is very funny and un-Tagalog of me. This is the answer I couldn’t fit into my literal mother tongue.

I often asked my mother to teach me Tagalog when I was younger. “Ah, you want to learn?” she’d say. She’d simply start speaking Tagalog to me, and when I couldn’t understand, she’d laugh and begin speaking English again. “You don’t need it,” she said, and that would be that.

Eventually she tired of my pleading and bought me two instructional tapes for Tagalog when I was 10. I still remember the white plastic case and the font TAGALOG! in blue. I played them once, and I remember the speaker said one word in English, and then the same word in Tagalog. It seemed to be going very slow. Not at all at the clip of my mother’s voice on the phone, speaking to relatives and friends all over the world.

In a few weeks I’d misplaced the tapes. In my mother’s eyes, my misplacing my belongings was a capital offense, since she grew up in a household in post-war Manila where she did not have any belongings of her own to misplace. From then on, whenever I asked her to teach me Tagalog, she’d say, “You lost the tapes I gave you! Find those tapes and study that.” In English, of course.

All of her refusals to teach me, in retrospect, seemed like elaborate covers for the real reason, which she finally revealed to my youngest brother, who, at 7 years old, took up my complaints as to why she didn’t teach us Tagalog. We were driving, and she sighed and looked at him in the back seat and finally said, “I didn’t want your dad to feel left out.”

My dad is a white Italian-American New Yorker, with no Tagalog other than the occasional “Salamat,” or “Ate.” Ah, I thought. I don’t want my dad to feel left out either. But, I thought, what if we promised not to use Tagalog around him? What if we translated everything honestly? Or what if we taught him Tagalog too?

I did not attempt these negotiations out loud. I worried my mother would bring up the lost tapes again. But that day she relented and taught my youngest brother numbers one through four, which he began to sing constantly. “Isa, dalawa, tatlo, apat.”

My parents divorced soon after, anyway.

So, yes, that’s why it took me until age 27 to learn the “Bahay Kubo” song. I still don’t have it memorized. But I’ll keep watching the little Australian kid for practice.

To the Fil-Am Dude I Met in Quezon City, Who Told Me This Was His Experience: “I’m trying to learn Tagalog too, but my relatives never expected me to know it. They always gossiped around me and kinda forgot I was there. So whenever I hear Tagalog now I go into this weird autopilot. Where the words just kinda flow over me. It’s hard to fight that weird feeling sometimes.”: Yes.

To the Friends Back in NYC Wondering if It’ll Be Hard For Me to Meet Fellow Lesbians in Tagalog: I was in a gift shop two weeks ago, looking for a wood carving or snack to send you, when I saw a lady working the counter of some wooden rice paddles I thought were pretty. I entered into discount negotiations with her about the rice paddles. I stayed engaged with her longer than I needed to, because there was something about her that felt familiar. She wore baggy jeans and chunky sneakers and a tight-fitting t-shirt. Her hair was cropped and shorter than mine. She grinned out of the side of her mouth and seemed to swagger a little.

“This rice paddle is ‘kamagong,’” she said. “The darker the wood, the harder it is, the more likely it is to last. The light wood is nice, but if it were me, I would choose the dark wood for longevity.”

I was in Palawan at this particular stall because a friend was visiting me from DC. My DC friend approached behind me, wearing a dress, because she is a dress-wearer, and the saleslady’s face lit with the same recognition I’d felt. She looked from my friend to me.

“Ah!” she said. “Is this your girlfriend?”

“No way!” I said, and grinned. “She’s not gay, I’m not that lucky.”

“Ah, just your friend,” said the saleslady. “But wait. Are you like me?” She grinned.

“Nah,” I said, “I’m a soft butch. I think you’re a t-bird.”

The lady guffawed. “Right on! I wanted to ask you earlier but I thought you’d be mad. You can get married now in New York, that’s good! I saw it in the papers! It’s hard here, I don’t think that’ll ever happen for us. My girlfriend was here yesterday and we went to church together. Do you have a girlfriend back in the States?”

“Maybe,” I said, and I smiled. She high-fived me. I walked away from the lady’s booth with a new rice paddle.

To Ate Susan Again, in Slightly Better Tagalog This Time: Mahaba ang anak mo. Parang hindi siya mabaho. Pasensya po.

To Anyone Wondering Who My Current Tagalog Teacher Is: She’s 70, exceedingly patient, wears necklaces as elegant and elaborate as her interchangeable fans, and whenever I make a Tagalog error, she folds up her fan very fast and gasps. When I use Tagalog correctly, she smiles and says, “Tama!”

Today, I had this conversation with her.

“Nagsulat . . . ako, isang essay . . .”

“Salaysayin. And if it’s future tense, nagsusulat.”

“Nagsusulat ako ng isang salaysayin . . . nagaaral . . .”

“Pag-aaral.”

“Ah, okay. Nagsusulat ako ng isang salaysayin . . . tungkol sa pag-aaral ko ng Tagalog.”

“Tama! Sana’y gumaling ikaw sa Tagalog.”

“Sana’y gumaling ako sa Tagalog. Opo.”

Laurel Fantauzzo will be in the Philippines until December 2011 on a Fulbright scholarship for her writing project, “Jolli Meals: The Rise of Filipino Fast Food.” Check out filipinofastfood.tumblr.com.

Delightful. To Laurel Fantauzzo: Sana na sa Pilipinas tayo. Or sana kasama tayo sa Pilipinas… Or…something like that. Ay naku.

Very good article.