How WWII hero Josefina Guerrero struggled with deportation

She was known by several names not because she had to hide behind several layers of identity as a spy. Her life just spun that way.

She was born Josefina Veluya in Lucban, Quezon in 1917, got married at age 16 and became Josefina Guerrero. As a spy for the U.S. during World War II, she assumed the name Billy Ferrer. In 1945 as the war was winding down, she wrote an American nun in California about leper conditions in the Philippines and signed it Joey Guerrero, a name that became familiar to her American friends when she lived in the U.S. from 1948.

In the U.S. she married a Vietnamese immigrant and became Josefina Guerrero Lau. When their marriage ended, she changed her name to Joey Leaumax. She died on June 18, 1996 in Washington D.C., known only as an usher of 17 years at the Kennedy Center. Many were unaware of her selfless act of heroism during World War II.

As a young mother, Joey was afflicted with leprosy. The disease forced a separation between her and her husband who took their daughter with him. At the time, leprosy was incurable and highly contagious, and lepers were treated as outcasts.

When war broke out, she volunteered to join the resistance movement. Although she was resigned to the idea of facing slow death, she wanted to do something with the remaining years in her life.

The guerrillas were skeptical because she looked young, but gave her her first assignment to test her resolve: she was to report all movements in the Japanese garrison. To their surprise, Joey managed to get an invitation to a Japanese camp where she asked a lot of innocent-sounding questions. When she got home, she provided the Americans information about a secret tunnel, complete with a drawing of a map.

While leprosy took its toll on her body it worked in her favor as she engaged in espionage. She became an ideal asset for U.S. troops because Japanese forces, repelled by her skin infection, did not inspect her thoroughly. She was free to cross enemy lines, no questions asked.

Soon, she was given tougher assignments, working as a courier and carrying messages from one unit to another;

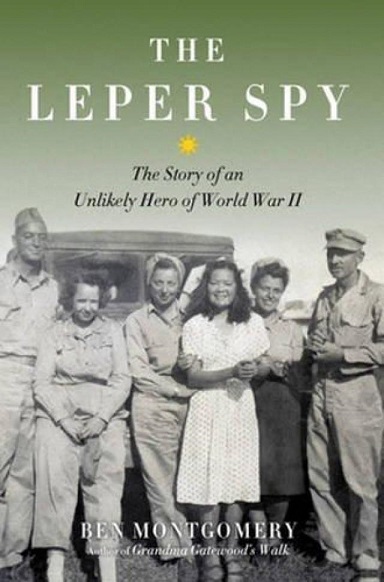

“At first, Joey carried the messages inside her hair, which she twisted and curled and bunched up in a chignon…The guerrillas told her that if she was

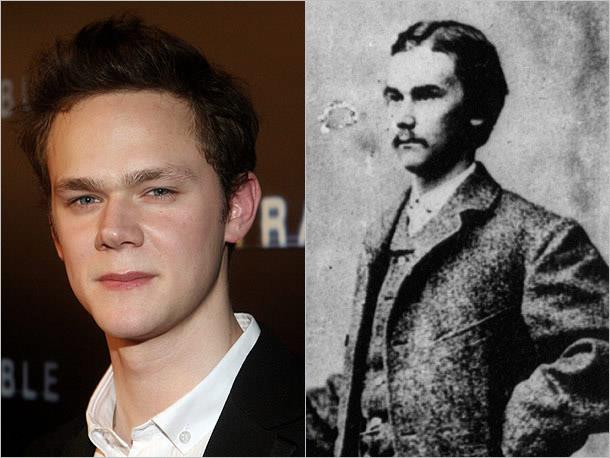

caught, they’d never heard of her,” writes award-winning Tampa Bay Times journalist Ben Montgomery in “The Leper Spy: The Story of an Unlikely Hero of World War II.”

Her missions would become more challenging: hiding military diaries, mapping artillery locations, smuggling medicine and food to POWs, hiding spare tires that contained bombs. As a spy, she was invaluable and smart; as a leper spy, she was feared.

As noted in the book, “The Japanese were culturally horrified of a disease they misunderstood…They feared being anywhere near someone afflicted.”

After the war, Joey received a Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm from the U.S. government, citing her work during the wear as showing “more courage than that of a soldier on the field of battle.” She was credited for saving the lives of many American soldiers.

She came to the U.S. heralded as a hero. The U.S. gave her temporary visitor’s permit to live in a leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana for treatment. For the first time, says the book, the U.S. government did something it had never done: welcome a foreigner with leprosy.

Over the years, there would be questions about her temporary visitor’s permit. She faced the prospect of deportation, but always the public would rally behind her and lawmakers would file bills seeking to bestow citizenship on her. While at Carville, she married Vietnamese immigrant Alec Lau, who was also undergoing treatment for leprosy. He is a permanent resident of the U.S. She and Alec would move to San Francisco, her leprosy contained by this time. After filing for divorce from her Filipino husband, Joey would be granted U.S. citizenship.

She moved to Washington D.C. single once again after her marriage to Alec ended. She died at age 68, as Joey Guerrero Leaumax, a woman who had “chosen to be alone…chosen to be forgotten.”

I was named for Joey. My mom met Joey when she was at the hospital in Carville and mom was at LSU. Joey was very much a loner, but stayed in touch with my family for all her years. She was such a brave woman and I’m honored that I carry her name.