Across the Korean Peninsula, unease in the morning calm

By Joel David

News about the latest saber-rattling from the pseudo-socialist feudal monarchy of North Korea still has the capacity to upset folks back home in the Philippines, despite the fact that South Korea happens to be, after Mongolia, the farthest East Asian country from the archipelago. Our connection with the peninsula goes deeper than the appreciation of ‘telenovela’ and K-pop products shared by our neighbors and now, thanks to Psy, the rest of the world.

The Catholic sector claims to having had historical precedence in Philippine-Korean relations (a pre-20th-century martyred missionary was supposedly trained in Asia’s first Christian outpost), but the more vital connection was realized by the Koreans first, prompted by their traumatic initiation in their experience of colonization: When they sought the help of Western powers to support their resistance against Japanese occupation about a century ago, they realized that the first country they expected to help them, the U.S., had effectively agreed (in the Taft-Katsura Memorandum) to allow Japan its “right” to annex Korea as long as Japan in turn recognized the U.S.’s claim to the Philippines.

From that point onward Korea and the Philippines would be bound by America’s Asian interests. Filipinos responded to South Korea’s call for assistance during the Korean War, earning admiration from the beleaguered population for their level of prosperity, second then only to Japan.

The Koreans’ cool attitude toward their former colonizers is key to what has since become a genuine alternative to Western-style development, where an aspirant to First-World status jump-starts (and sometimes maintains) its journey to material progress by forcibly exploiting an “other” population, whether within its borders (as slaves) or in another country, with plunder and extermination constituting extreme but (from the colonizer’s perspective) occasionally necessary measures.

What South Korea (henceforth Korea) had wrought since then, which several other non-East Asian nations managed to replicate, was an attainment of developed status using the formula claimed but never actually deployed by the originary European model: sheer hard work, where in effect the capitalistically exploited group is the native population itself. Such an option could only be available to genuinely decolonized states – and once the U.S. extended its imperial Cold War arrangements beyond Latin America to include the Philippines, that model had less than a snowball’s chance in Manila of surviving on our shores.

Yet within the interstices of covert premises that distinguish marginal relationships (the political as much as the personal), it would be possible to assert that Koreans found their inspiration in the early Philippine example; in much the same way we could aver that Filipinos also persisted in their pursuit of the now-patentable Asian model developed, pun intended, by Korea, in spite of the U.S.’s inescapable neocolonial stranglehold, not by resisting their colonized condition but by embracing it and proffering the only products they can lay claim to – their literal selves – to any master willing to take possession of their services.

This admittedly hasty account helps explain, on the one hand, why among East Asians it is the Koreans rather than the more historically empire-minded (and populous) Japanese and Chinese who found vast and open acceptance in the rest of Asia via their popular cultural products; and on the other hand, why it is the Philippines that has become the Koreans’ favorite single-country destination.

As Filipinos, we shortchange ourselves if we believe that our English-language expertise and our tropical-paradise resorts have sufficed in attracting the hardest working, least self-forgiving nationals in the world, a people who deal with their distinction of having the highest unhappiness indicators (divorce and suicide) among OECD member-countries not by easing up, but by hunkering down and driving themselves even more mercilessly.

The trade-off becomes apparent to the increasing numbers of Filipinos who arrive in Korea as workers and/or spouses and participate in a highly regimented system where historically uninterrupted Confucianist patriarchy has fused with Western orthodoxy so successfully that the observance of hierarchical orders (the young deferring to the old, women deferring to men, and so on) has achieved the semblance of an all-encompassing secular religion: the government can set an audaciously precise goal (recovering from recession, for example, or introducing a microtechnological innovation) and the rest of the nation moves accordingly to ensure it arrives, as announced, on schedule. For this reason, long-time foreigners have learned to respond to unusual events such as North Korea’s latest noise barrage by taking the cue from the local population: their contemptuous dismissal of the stink being raised by the big boy across the DMZ rings louder by being so utterly silent. Try invading again, seems to be the sentiment, and see whether you’ll ever want to return to your old regime after taking in wonders your imagination can’t even begin to comprehend.

They may as well be addressing the Filipinos too, but the Philippines has a ready retort: free from the developmental treadmill that has the other Asians running just to stay in place, and much wiser after realizing how easily the American dream can betray most of its purchasers, the people of the islands can be as free as they wish to be, as cynical of the values that Western (and Westernized) peoples hold dear, and as kind as only those who have nothing to lose can get. Until one of a multitude of masters from foreign shores comes calling, life can be beautiful, as it was always meant to be.

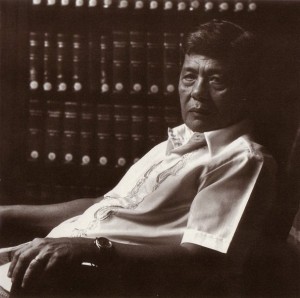

Joel David is professor for Cultural Studies at Inha University in Incheon, Korea. He is the author of a number of books on Philippine cinema and was founding Director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute.

Trust our award-winning law firm with your immigration case.

Trust our award-winning law firm with your immigration case.

Katamisán Cakes: French technique, tropical flavors. Weddings & special events. Click for info.