Wanna Ver’s ‘cathartic’ meeting with torture survivor (Part 2)

By Wanna Ver, Atmi Pertiwi, Leonardo Taddei, Jody Fish, Adolfo Canales

Recognizing the ‘Golden Age’ myth

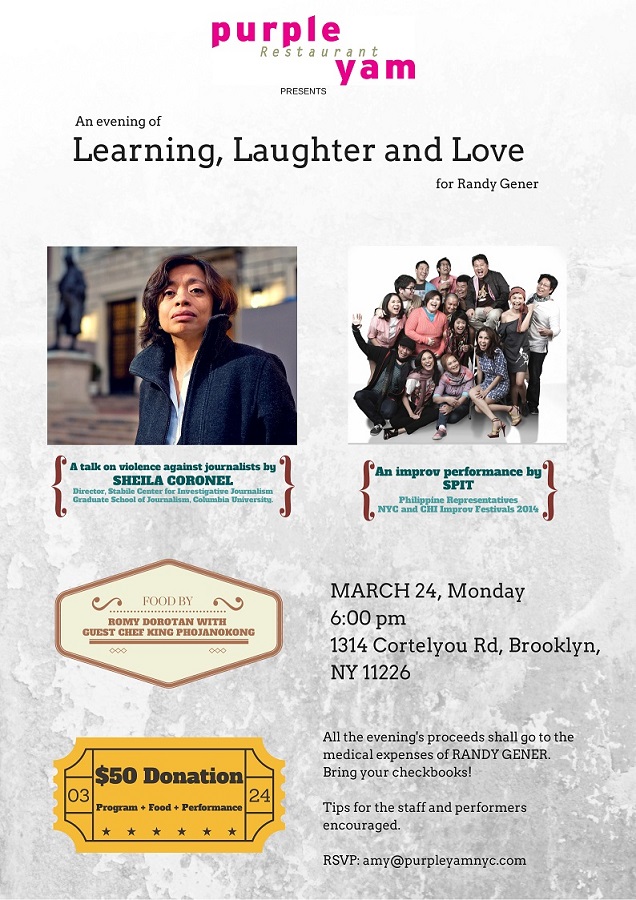

A year after her child’s birth, Wanna Ver reconnected with Michelle so she could come clean about her father. “Michelle almost fell over”, Wanna recalled. “She had to put her hands on the ground to hold herself up and she could barely breathe. She couldn’t believe it, she kept asking if I was the granddaughter, and I kept having to repeat: ‘I’m the daughter of General Ver.’”

Wanna asked to hear Michelle’s story and to be introduced to other survivors who might want to share their own stories. She introduced Wanna to Nolasco ‘“Noli” Buhay, who was wrongfully arrested, detained and tortured by the infamous 5th Philippine Constabulary Security Unit in 1973. “They tortured me a lot, undressed me, kicked me, hit me,” said Buhay. “I collapsed and could not feel anything after that. The second day was the same, and eventually I was bedridden.”

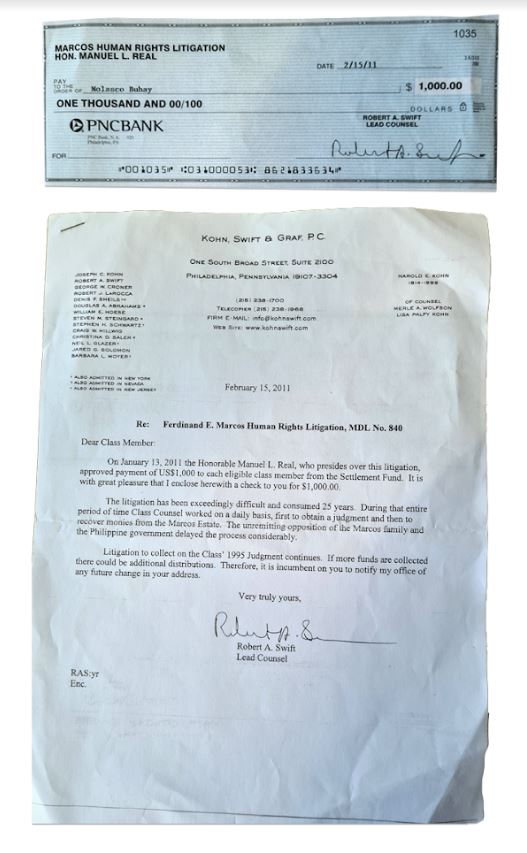

In 2011, 38 years after his release, Buhay received a $1,000-check as compensation from the government, a recognition of what had been done to him. This, he said, “gave me some relief that justice was being served.” To him it was “evidence of the Marcos family´s human rights violations and theft of the Filipino people’s resources.”

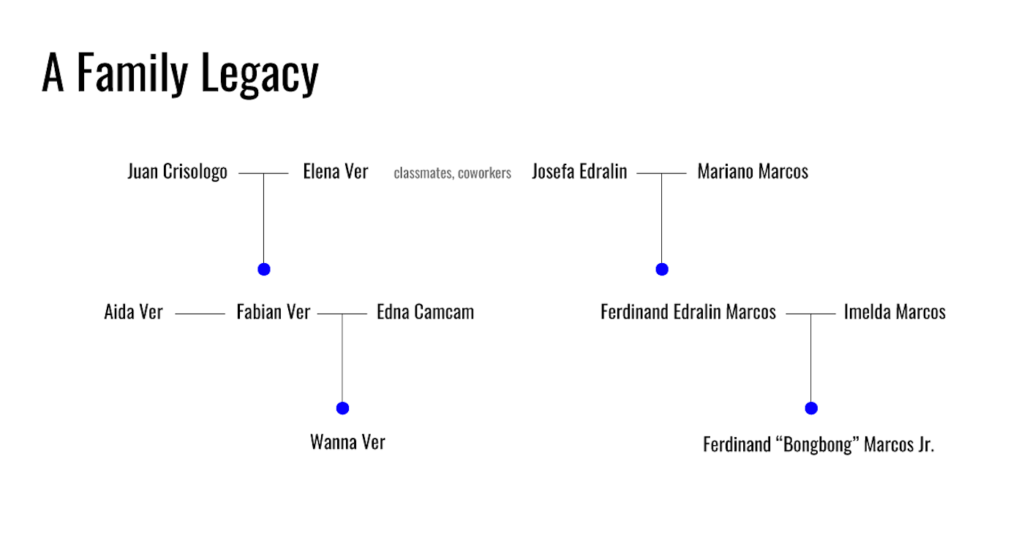

Noli sought asylum in Sweden after his arrest and founded the Swedish-Filipino Association to support democracy in the Philippines. Buhay’s story, among others, helped Wanna recognize that the state, under Marcos and her father, had deliberately concealed the brutality of the Marcos regime from her and the Philippine public. She realized the Golden Age narrative had been propagated to obscure the documented facts and paved the way for the restoration of the Marcoses to power.

“We all noticed the cathartic nature of our meeting”, said Wanna. “I know I am not at fault for my father’s actions, but I believe listening to survivor accounts and offering an apology on his behalf requires relatively little effort on my part, and could potentially alleviate substantial suffering for them.”

This meeting and those that followed eventually resulted in the formation of Kapwa Pilipinas, an organization that promotes empathy and reconciliation for victims and perpetrators of human rights violations. Wanna, along with Michelle, Buhay and his wife were among the founders.

“It would be difficult for Marcos Jr. to revise history and dispute our past while a Ver is trying to record it,” said Buhay.

Seeking elusive justice

The team also interviewed abuse survivors, including writer Aida Fulleros Santos-Maranan, who was arrested in 1976. Maranan said she was physically abused, sexually molested, and psychologically tortured by being forced to play Russian roulette. Many arrests like hers were not recorded, she said, and although more than 11,000 Marcos victims had received compensation, many more were found ineligible. The government’s Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board was not given enough time and resources to conduct a thorough investigation, she said.

The trail of martial-law abuses led to the United States and the cases of Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes, U.S.–born Filipino labor union organizers and U.S. citizens who were murdered in Seattle in 1981. Their deaths were part of a Philippine intelligence operation to suppress anti-Marcos dissidents abroad.

In 1987, Seattle-based public interest lawyer Michael Withey, representing the Domingo and Viernes estates, deposed Ferdinand Marcos in Hawaii for four days. They won a $15 million federal court jury verdict—the only case in history where a head of state of a foreign government has been convicted for murder in the U.S.—and negotiated a$3-million settlement.

The team also reviewed the documents of Trajano vs. Marcos, a court case filed in Hawaii. Wanna saw her father’s name on one of the documents and again realized that, “It is not just a matter of claims or PR campaigns to tarnish the Marcos name. There is documentation, there were court cases, witnesses, a judge, a jury. They committed crimes against humanity. It may have been golden and shiny for us, but for them it was brutal, bloody and poverty stricken.”

In 1995, U.S. human rights litigator Robert Swift won in Hawaii court the first worldwide human rights class action lawsuit, one filed against the Marcoses on behalf of 9,539 martial law survivors and their heirs. The case was settled for $1.964 billion worth of U.S.–based Marcos assets. In 2013, the Philippine government authorized the release of $245 million from the Marcos wealth as compensation for human rights victims.

“I couldn’t understand how Marcos loyalists and Golden Age believers, myself included, could accept that no human rights atrocities occurred if thousands of people—enough to make a class action case—won in court and were financially compensated,” said Wanna. “To me this is crucial: it’s undeniable proof that this really happened.”

“The majority of my family believes that people need to ‘forgive and bury the hatchet for the sake of our nation and the people. But I disagree. I feel this view implies that the Golden Age story and the Never Again story are somehow equal when they are not. Most of the people who suffered under Martial Law, who suffered systemic oppression at the hands of the Marcos regime were student activists, farmers, informal settlers, the masa.”

Still Wanna confessed to being torn about her father, a man known colloquially as Ver-dugo at the height of martial law–wordplay formed by his surname with berdugo, meaning “executioner.”

“This is a long learning process,” she said. “He’s still my dad, and somewhere deep down, I still hope I’ll find something that shows that there had been some kind of mistake, or that somehow his signing a paper is not as bad as him holding a gun to someone’s head, but I haven’t gotten there yet.”

For now, Wanna is offering one apology at a time for the crimes her father helped commit, and stands by the accounts of victims and survivors.

“In our culture we are taught to respect our elders, you know, utang ng loob, we are indebted to them.” she said. “But I think it’s important to do our own research and to forge our own beliefs, look outside of what our family told us to believe. We need to listen to each other and acknowledge wrongs done before our country and people can heal and move forward. When my daughter grows up, I want her to be able to know her history and lineage without avoiding it, like I did. The shame I’ve carried for years can be debilitating. Still, I’ve learned that with work, it can also be transformed into healing.”

This article is the product of a collaboration between Wanna and her classmates at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, who reviewed documents and data related to human rights abuses during the Marcos regime.