On Global Filipinos: Ninotchka Rosca: Writer and activist of influence

By Loida Nicolas Lewis

The Pulse Asia and the SWS January 2022 Polls for the Philippine elections three months away were devastating to the campaigners of Leni Robredo and exhilarating to the followers of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. It showed that Marcos Jr. is almost 30 points ahead of Robredo in the presidential race.

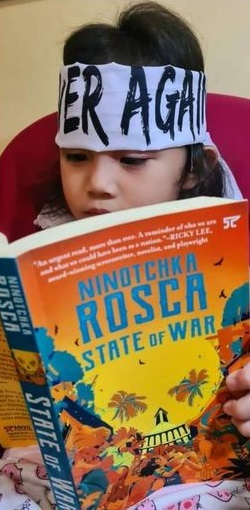

Because Marcos Jr. brings back the dictatorial martial law years of his father former President Ferdinand Marcos, Ninotchka Rosca’s 1988 novel “State of War”has been released by Anvil Press with a blurb from Senator Kiko Pangilinan. The U.S. edition, available at Amazon.com has a different cover without blurbs. For the Philippine edition, Ninotchka had presciently secured Sen. Pangilinan’s comments three years earlier, impressed as she was by the senator’s active and effective leadership for the lowly Filipino farmers and his love for literature.

On September 21, 1972, when President Marcos declared martial law, Ninotchka herself was picked up in her home early in the morning of October 10, 1972 and jailed at Camp Crame. It is her experience and knowledge of what happened in Camp Crame in particular and in the country in general that formed the nucleus of her obra maestra “State of War” which took her six years to complete.

Why did she write “State of War”? In her own words,“I wrote it because I was homesick. I was stuck in Hawai’i on my way home at the end of my writer’s fellowship, but my mother called and said I was on the hold-order list at the Manila airport. The family found out when my younger sister was leaving for Japan and she was mistaken for me; they tried to haul her off for interrogation. Also, I felt the need to tell the stories of people I had known and the oftentimes horrifying experiences they went through. I remain amazed by the longevity of this novel. It must hold certain truths that people find relatable.”

She was fingerprinted (“Naku, ang lambot ng kamay mo,” a solder shouted), placed in a gym with 250 politicians, writers, journalists, suspected leftists, all men and just four women. She and 10 other women were given a small room separated from the men. As the number of women detainees increased, they were transferred to another building, whose windows were covered by burlap sacks. The worst thing was the uncertainty and the utter cruelty of the guards when any one of them was not following their instruction or showing defiance.

She detested the situation of Filipinos doing their dastardly acts towards their fellow Filipinos.

She remained in jail for six months until three soldiers raped and killed a young woman in a holding cell of another building. Because the girl said she would file a complaint against the rapists, the soldiers poured muriatic acid down her throat. They then claimed that she committed suicide. Her parents were also persecuted when they tried to investigate and protest the murder of their daughter. Ninotchka suspects she was released as a kind of damage control because of the ensuing scandal over the girl’s murder, the first but soon would not be the last to occur at Camp Crame.

For five years, Ninotchka gathered donations for the underground resistance while she working in an investment company, at the same time writing as a journalist. When she was tipped off that she was going to be arrested again, and this time, the threat of being executed was more real than before, Ninotchka decided it was time to go into exile. A friend in the U.S. Embassy got her into an international writers’ program in the United States, where she has lived ever since.

Her name, derived from the 1939 Greta Garbo movie, made her a writer with a singular monicker. But in due time, as she became known for her writings, she would learn of several baby girls in the Philippines named after her.

A famous line spoken by Greta Garbo as Ninotchka, “Don’t make an issue of my womanhood” has followed Ninotchka’s career as a champion of women’s rights. She was a founder and first national chair of the largest and only U.S.-Philippines women’s solidarity mass organization GABNet. She represented a U.S. women’s organization at the 1995 United Nation World Conference on Women in Beijing, China and was with Amnesty International at the 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, Austria. There, she drafted the Survivors Statement where the phrase “modern-day slavery” was applied to the trafficking of women.

She was press secretary at the International Women’s Tribunal on Japan’s WWII Sex Slavery which convicted Japan’s wartime era for using Comfort Women as an instrument of war.

Aside from “State of War,” Ninotchka wrote “Bitter Country and other Stories” (1970), “The Monsoon Collection (1983), short story “Epidemic” (1986), “Endgame: The Fall of Marcos” (1987), “Twice Blessed” (1993 American Book Award), “Jose Maria Sison: At Home in the World – Portrait of a Revolutionary” (2004, co-authored with JoMa Sison), short story “Sugar & Salt” (2006), “Gang of Five” (2004), “Stories of a Bitter Country” (2019).

When she got the American Book Award for “Twice Blessed”, she confessed, “The only other person who had received this award before me was Bienvenido Santos — ironically, one of the teachers at my first writing workshop. I was somewhat astonished when I received the plaque. Also, a little embarrassed. The book is about the Philippines and I get an American award. For months, I hid the plaque in a desk drawer. At the time I was writing this novel, there were so many books about the Philippines and the Marcoses already — however, I felt that most missed the experience — the texture, as it were — of being at the center of the Goth politics of the country.”

When asked why she became an activist and a writer, she replied, “I was involved in organizing against the use of UP as a research laboratory for the war in Vietnam. I received a message from an editor that their magazine was interested in doing an article on the topic and would I be willing to share what information we had. To this day, I don’t know what made me reply, “Only if I write the piece myself.” That was how it started. It seemed like another pre-ordained path.”

When Ninotchka learned to read Tagalog at 7 years old, the neighborhood ‘katulong’ (household helps), ‘lavandera’ (washerwoman), and ‘tsuper’ (driver) would ask her to read to them once a week in the afternoon Liwayway magazine and the Tagalog Comics. They would sit in front of her when she read the stories in Liwaywaywhich was an all-text publication. They would stand behind her as she read the comics so they could see the illustrations. It was the equivalent of watching television which was not available at that time in Laguna, Bulacan, Manila – Ninotchka’s maternal clan residences.

It could have been the influence of Ninotchka being the writer and activist of influence that she has become, when she enjoyed entertaining her audience with stories of the imagination at such a young age.

© The FilAm 2022