The legend of Ferdinand Marcos began a hundred years ago: journalist Sheila Coronel

Investigative journalist Sheila Coronel delivered a cogent and well-chronicled presentation about Ferdinand Marcos, the former Philippine president and rapacious dictator and father of now presidential aspirant Bongbong Marcos Jr.

In Coronel’s lecture — organized by the Adrian E. Cristobal Lecture Series and the Unyon ng Mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas – she reflected on the rise of Ferdinand Marcos and how his acquittal for the 1935 Nalundasan murder may have foreshadowed what was to come. We didn’t call it impunity at the time.

Her narrative was told alongside the story of her own family and how her father ended up becoming Ferdinand’s lawyer. The Coronels (Ilocos Sur) and the Marcoses (Ilocos Norte) are both Ilocano families.

While appealing his murder case, Ferdinand graduated valedictorian of his class, studied for the bar, and topped the exam. The Supreme Court justice who argued his case was in awe, saw a brilliant man who could become an asset to the country. At the tender age of 18, said Coronel, Ferdinand learned lessons on chicanery and political murder.

Excerpts from Coronel’s lecture below:

I was a martial law baby. My generation grew up watching the unending spectacle of Ferdinand and Imelda. Remember this was the 20th century long before YouTube and Netflix. There were only five TV channels and three newspapers, all owned by Marcos cronies. We didn’t call it fake news then but it was vintage 1970s propaganda. Obvious and crude.

I was in first grade when Marcos was first elected president. I studied across the street from Malacañang in a school for girls run by the Sisters of the Holy Ghost. I remember that in the 1960s the streets around the presidential mansion filled with traffic and commerce. On Thursdays hundreds flocked to the church nearby to pray to St. Jude, patron saint of hopeless causes.

I was barely in my teens when martial law was declared. Suddenly, the streets were silent. The palace gates were shuttered. Barbed wire barricades kept people away. The neighborhood, the entire country was hushed.

Marcos was still president when I finished high school. He continued to issue decrees from his barricaded palace when I went up to college, graduated and got my first job. My generation had reached adulthood with no memory of any other president. Most of us didn’t know that while we were growing up thousands of dissenters had been tortured, killed or jailed, that in faraway villages the army had been let loose to pillage, rape and murder. That the Marcoses were stealing our money and squirreling it in Swiss banks and Manhattan real estate. We didn’t read any of that in the news. Instead, we were entertained. Mohamad Ali beat Joe Frazier in the Thrilla in Manila. We had beauty pageants, the Bolshoi ballet, Van Cliburn, international film festivals. We watched the Marcos party with Brooke Shields and Cristina Ford. George Hamilton twirled Imelda to the tune of “I love the nightlife,” while Gina Lollobrigida photographed Ferdinand. Imee was being matched with Prince Charles. The Marcoses behaved like royalty so we were not surprised that in yet when another Marcos inaugural, the choir sang ‘and he shall reign forever and ever.’ Marcos was the messiah.

How did we think we can get rid of him so easily? The truth is that the Marcos mythmaking began long before I was born. Not in my generation not even my parents’ generation. It began with my grandparents’ generation. Today we blame social media disinformation and the textbooks that glorify Marcos and martial law, but the lies, evasions, elisions, exaggerations were sowed almost 100 years ago. If they are difficult to weed out now, it is because they are so deeply rooted.

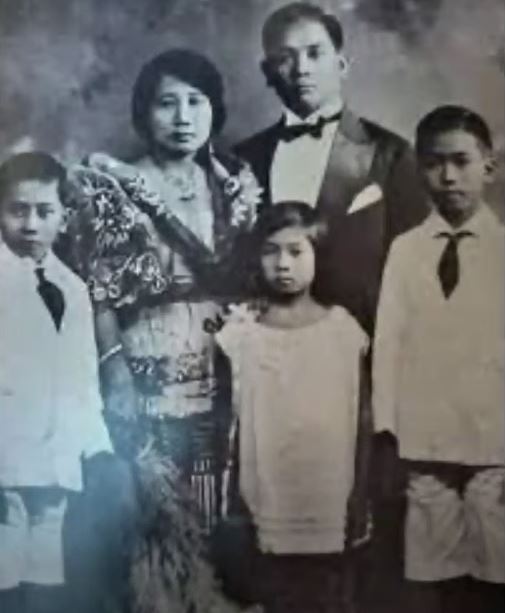

My grandfather Juan B. Coronel was born in 1909. He was a school teacher in Sta. Cruz, Ilocos Sur. So is my grandmother Victorina Pimentel. Marcoses parents’ Mariano and Josefa were more than 10 years older than my lolo and my lola. And they too were school teachers. They were among the first generation of Filipinos to be educated in English in the public school system set up by the American colonial regime. Mariano eventually gave up teaching, took up law and went into politics. In 1935, along with his friend and ally Gregorio Aglipay, he ran in the first-ever election of the Philippine Commonwealth. Aglipay ran for president against Manuel Quezon, Marcos as representative of Ilocos Norte in the National Assembly. Both of them lost, Marcos to his longtime rival Julio Nalundasan.

Not long after the results were announced, Nalundasan’s triumphant followers paraded around town in cars and trucks. One of them carried coffins with Aglipay’s and Marcos’s names on them. The revelers lingered in front of the Marcos home in Batac and shouted “Marcos is dead.” For the Marcoses, this was, in the words of the Supreme Court, both provocative and humiliating. We all know what happened next.

The following night Nalundasan was shot and killed. The principal suspect: Ferdinand Marcos. Champion shooter of the ROTC rifle team. He had then just turned 18. A court in Laoag tried and found him guilty but he made an impassioned plea to be allowed to continue his law studies while in jail.

Ferdinand was bad-ass. Here was the valedictorian of his class acting as his own lawyer and appealing the ruling while studying the bar. He topped the 1939 bar exams, wrote an 830-page brief to the Supreme Court and argued his case in an all-white sharkskin suit. He was acquitted and saved from the death penalty. By 1940, the wide publicity given the case had made him a legend.

If you were Ilocano like my grandparents, from a part of the country that was hardscrabble poor, its people living on land wedged between mountain and sea, famous for their frugality and work ethic and who value family and honor, you would be cheering for him too.

Up to now we don’t know who killed Nalundasan. We do know that Jose P. Laurel, the Supreme Court justice who wrote the decision, was Marcos’s law professor at UP. It was he who convinced the high court to reverse the conviction by arguing NOT that Marcos was innocent but the country needed brilliant people like him. The justice’s son Jose III was Marcos’s classmate since high school and his Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity mate. It was he who drove Ferdinand to Malacañang so President Quezon no less could congratulate him on his acquittal. Jose Jr., Justice’s Jose’s son would tell me all of this when I interviewed him many years later. Like so many other politicians of that era he likes to tell the Marcos-Nalundasan story. It was legend.

(C) The FilAm 2022

Great site.