The Pastillas Scandal and the sneaky ways to corruption

By Cristina DC Pastor

There’s something sweet and savory about corruption in the Philippines.

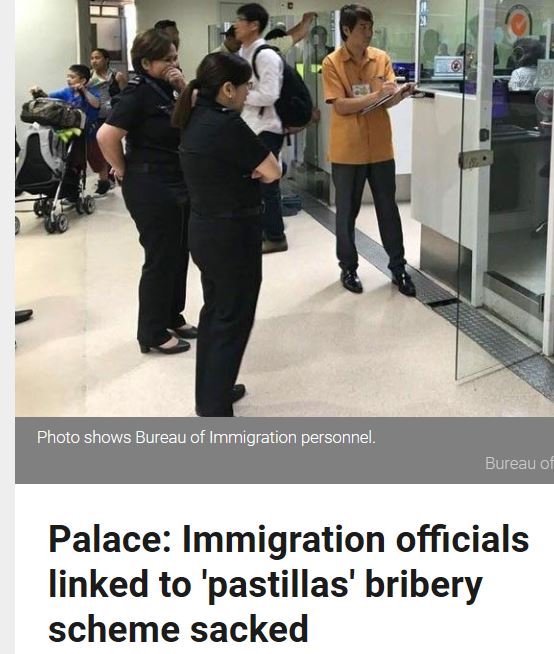

Some Bureau of Immigration (BI) officials and personnel are said to be receiving P10,000 per from Chinese nationals entering the Philippines to illegally work in gaming casinos. The cash is bundled up and hidden in Pastillas wrappers, according to reports.

I am already imagining Pastillas de Leche nicely rolled in dainty Papel de Hapon meticulously hidden in some bureaucrat’s drawers rather than passed around and savored the way you would these delicious soft milk candies drizzled in sugar. If you think that’s way too wild, sorry but that’s what Pastillas (of the Goldilocks variety) means to me: A delicious ‘balikbayan pasalubong’ gift from the Philippines.

The Pastillas bribery scandal is now under investigation in the Philippines Congress after it was revealed that certain Chinese nationals were given “special treatment” in exchange for pretend Pastillas. Five BI officials have been fired and about 20 personnel were suspended. While the Philippines continues to be a low performer in Transparency International’s Corruption Index, the inventiveness, audacity and gall with which it was carried out by low-level bureaucrats seem to exhibit a creative tack around the government’s anti-corruption law.

Back in the day, some drivers who did not want to be bothered by pesky traffic cops would make sure to leave a P20 bill folded underneath the driver’s license. It’s the police officer’s for the taking. The officer teases out the bill from a plastic case and then waves the driver off. No word spoken, except perhaps for a breezy, “Ingat lang, sir.”

The same timeworn practice has been anecdotally documented at some airports around the country. A P20, P50 bill folded and hidden in one of the pages of a passport. In one of my foreign travels as a young reporter, I remember one of my editors’ astute advice: “Ipit ka lang ng bente para dere-derecho ka lang.” I never had to use it having found out that a press card had more of a desired effect.

We’re talking low-level corruption, the ways some bureaucrats make a little money to augment their meager salary. Not the ways of Presidents and congressmen and army generals which involve multiple offshore accounts registered under a shell company. When Imelda Marcos stuffed much of her ill-gotten jewelry inside Pampers diaper boxes when her family fled the country in 1986, it was a behavior not befitting a dictators’ well-heeled wife. But as a decision made in a crunch, no matter how tacky, it got the job done.

To understand corruption in the Philippines is to understand the deep-rooted way we give thanks as a people. We are generous to a fault when someone does something nice for us. There’s the huge tip for a friendly waiter; a prized gamecock for a wealthy compadre who gave your son a job; a government contract for the politician who delivered the votes in his province; a Cabinet position for the business tycoon who opened his chest during the campaign.

Transparency International recognizes that the Philippines “continues to struggle to tackle corruption.” Imagine P700 billion lost yearly to corruption. They end up enriching bureaucrats and politicians instead of being used to improve housing, the criminal justice system, or public education. Tracking down these riches is almost a fools’ errand.

Pastillas is a small-potatoes operation, part of a never-ending cycle of corruption where you have to make ends meet to survive in the Philippines. As is often the case, the bigger fish are never caught.

© The FilAm 2020