It’s over when the fat lady sings

By Luis H. Francia

In Ramona Diaz’s 2003 eponymous film, there is a scene where the former first lady—still quite a looker—spends an inordinate amount of time drawing her cosmic views on a pad. But these are comic rather than cosmic, made up of New Age blather. Fond of circles, she fills page after page with diagrams of the human and divine order.

Her words are as revealing as, if not more so than, what her critics have and continue to say about the fantasy world she inhabits, and her role in the human rights abuses and financial thievery committed under martial law, when she and Ferdinand Marcos ruled the country as their personal fiefdom.

Flash forward to the present. Lauren Greenfield’s The Kingmaker has an older and heavier but still impeccably groomed Imelda being driven in her van through the streets of Manila. Doling out cash at a stop light to the impecunious, she remarks with a straight face that during martial law the city had no beggars, that contrary to all the bad press the regime got, it was essentially a paradise.

As telling as that fabrication is, what is even more telling is the money bag always at hand, held by a factotum. At a children’s hospital, Imelda hands out thousand-peso bills to the cancer-stricken kids and their parents—an unintentional but ironic representation of a measly giveback to the very same masses from whom she and her late strongman husband stole a conservatively estimated $10 billion over two decades.

She’s proud of having befriended dictators such as Muamar Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein, and Mao Tse-tung. At one point, in an opulent, albeit tackily furnished living room, she complains of government harassment, and the sequestration of their material goods by the Philippine Commission on Good Government (PCGG), from paintings to jewelry. In an emotional outburst she complains that though she has more than a hundred bank accounts she is unable to access any of them. One wonders at the sheer number and where all that cash is coming from. She’s certainly the richest poor girl I know of.

Then there is Calauit Island. Part of the Palawan archipelago, it was declared by the Marcoses as a game reserve in 1976. Having taken a fancy to wildlife she saw while on a trip to Africa, Imelda had shipped to the island animals such as giraffes, zebras, and gazelles. In the process 250 families were evicted and relocated to another island with hardly any resources. One islander drily remarks that the Marcoses preferred the animals to live humans,

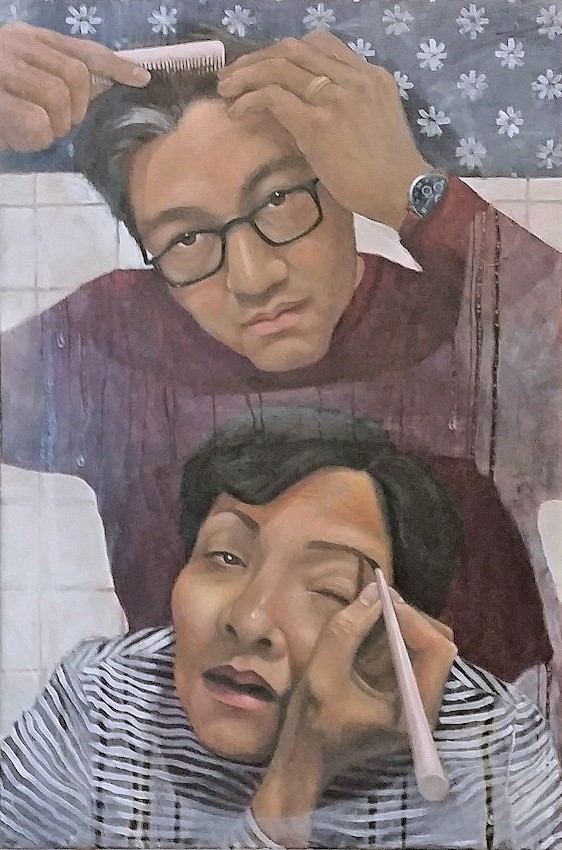

Through such details, rather than any one momentous revelatory scene, does Greenfield portray what lies behind the façade of the Iron Butterfly. With her helmet of hair, punctilious attention to appearance—she frets over the size of her belly—, powdered, perfumed, clad in a red terno and attended to by a retinue of aides, the former first lady views all the world as a stage. Like a veteran thespian, with the perpetual mournful air of a victim, she spouts lines that have been uttered countless times—lines that are for the most part unmoored from reality but that she has come to believe, utterly.

Her hopes for a restoration of la vida loca she pins on her son, Bongbong Marcos, whose aspirations to the presidency constitute a significant part of the film. Were he to succeed in his late father’s footsteps, Imelda would be the power behind the throne, hence the film’s title. But the pampered son seems to lack his father’s political bones, whining on camera about how, wanting to fly back to Manila from wherever he was, all he could afford was economy class. Alas, the contemplation of being with the hoi polloi was simply too much to bear. He cajoled a friend into providing him with a first-class ticket.

To achieve the presidency means an alliance with President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, a professed admirer of the late dictator and bogus war hero, who allowed the burial of his corpse at the Libingan ng Mga Bayani, or National Heroes Cemetery, an insult to a nation that suffered grievously under the conjugal dictatorship.

Greenfield includes footage of the marginalized killed in Duterte’s grim and brutal war on drugs. Earlier, Imelda anoints herself as the caring mother of the people, miming scooping up the masses to gather unto her bosom. It’s a grandiose and empty gesture, with nary a mention of those bereft of their loved ones due to this immoral and misguided war, a visceral link to the extrajudicial killings carried out when she and her husband were in power. It is a connection she can never make, a circle she will never draw.

Footage of protests then and now against martial law; interviews with Vice-President Leni Robredo, a critic of both the Marcoses and Duterte; and activists tortured by the Marcos regime, provide a counternarrative. One of them states, plaintively, that she doesn’t mind the return of the Marcoses from exile, but why give Imelda a platform to speak?

Her question will echo in the minds of many viewers, encapsulating a dilemma facing anyone who attempts a portrait of a justly maligned public figure: Does one then, in Imelda’s case, play into her agenda, or on the other hand provide enough of a nuanced and complex picture to undermine her credibility? Much as I wanted at times for Greenfield to be tougher on her, the film is smart enough to give Imelda enough rope to hang herself, while at the same time allowing a chorus of voices to expose her dark neurotic side, for which a whole country suffered. Copyright L.H. Francia 2019

This article originally appeared in the Philippine Daily Inquirer and is being republished with permission from the author.