Many haunting questions in Nick Joaquin’s ‘Larawan’

By Tricia J. Capistrano

Oh Candida, life is not so simple as it is in Art! We do not choose consciously, we do not choose deliberately—as we like to think we do. Our lives are shaped, our decisions are made by forces outside ourselves—by the world in which we live, by the people we love, by the events that fashion our times—and by many, many other things we are hardly conscious of.

-From “A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino” by Nick Joaquin

My parents wanted to get married in December. They had both come home from studying abroad and my paternal lolo, a probinsiyano who made it in Manila, wanted to invite all his friends and relatives.

In September, however, Marcos declared Martial Law. Large gatherings were suspect. So in early October, my parents’ closest friends and relatives gathered for their wedding at Santuario de San Jose in Greenhills and then a small reception in a restaurant on EDSA. Fortunately for the guests, my parents were good friends with the Ambivalent Crowd, a professional choral group in the ‘60s of which Celeste Legaspi and Leo Rialp were members. The group serenaded the guests; I think they even outnumbered them. As my parents and their friends grew older and had reunions, sometimes they would invite us children and we would be treated to impromptu concerts.

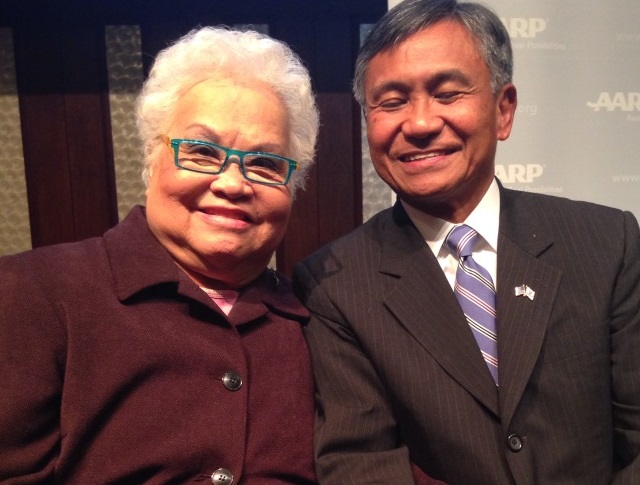

Seeing Celeste Legaspi, Leo Rialp, Robert Arevalo, Jaime Fabregas and Noel Trinidad—actors from my childhood—in the movie musical “Ang Larawan” during a freezing New York City evening last January was a heartwarming surprise.

“Ang Larawan,” based on Nick Joaquin’s play “Portrait of the Artist as Filipino” was translated into Filipino by Rolando Tinio and set to music by Ryan Cayabyab. Celeste Legaspi and Girlie Rodis produced the stage production in 1997 and this movie version, directed by Loy Arcenas. The movie musical premiered last October 2017 in the Tokyo International Film Festival.

In the 2017 Metro Manila Film Festival held last December, “Ang Larawan” took home Best Picture, Best Musical Score, and Best Production Design. In addition, Joanna Ampil who performed in “Miss Saigon,” “Jesus Christ Superstar” and “Les Miserables” in London was awarded Best Actress in a Leading Role. Ampil was amazing. She truly inhabited the role of the elder sister, Candida.

The movie welcomes you to a traditional upper class home in Intramuros, Manila. It is October 1941, shortly before the Japanese occupation. The two sisters, Candida and Paula are busy keeping house for their elderly father—ironing with a charcoal heated iron and mixing hot chocolate with a batirol. The family has fallen into hard times. Their father, a renown painter who stopped producing works, recently created a painting that critics are calling a masterpiece. The sisters wonder if they should keep it or sell. The bills are piling and they worry about how they will be able to continue to care for their father.

Their worrying tells us about the mores of the times, when upper middle class women were not supposed to work and were at the mercy of their husbands and brothers. And for those of us who have chosen to leave the Philippines, we are reminded of the binds of our culture–people’s expectations, what will the neighbors say? If I do this, what does it say about me? How does it reflect on my family? What is my duty to God and to my country?

Like many of Nick Joaquin’s works, “Ang Larawan” haunts you with questions and then leaves you in wonder at the beauty of your shared literary journey.

A rousing musical with prominent singers in the cast, such as Celeste Legaspi, Dulce, Zsa Zsa Padilla and Ogie Alcasid

In 2017, Nick Joaquin’s birth centennial, Penguin Random House released an anthology of Nick Joaquin’s works, “The Woman Who Had Two Navels and Tales of the Tropical Gothic.” Although his works are written in English, it was only last year that his works were published in the United States.

At the book launch at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York City, Filipino American authors Ninotchka Rosca, Gina Apostol, and Alex Gilvarry read excerpts from his short stories, “The Mass of St. Sylvestre,” “Dona Jeromina,” and “May Day Eve,” stories set when the Philippines was still strongly influenced by Spain.

Nick Joaquin, who was born in 1917 and lived through 2004, grew up reading books from his father’s library. His father was a colonel under Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo during the effort to gain independence from Spain. During the US occupation, Joaquin’s father worked as a lawyer. He died when Nick was 15. Nick’s mother, a teacher, taught him Tagalog, Spanish, and English. Nick lived through the American and Japanese occupation and the Marcos years. In 1976, Nick Joaquin was awarded the National Artist Award. He agreed to accept the award from Marcos administration in exchange for the freedom of fellow writer Pete Lacaba. After the Marcos years, he continued to write stories and essays about Philippine culture, politics, and history.

I cannot help but wonder what Nick Joaquin would write for us now, how he will opine about our new alliance with China, the thousands who were killed since the beginning of Oplan Tokhang, and then what he will say about the hundreds and thousands of us who even after our independence from foreign nations have chosen to leave the Philippines behind. How would he portray us?

When I first visited New York City in 1991, I was 17. Coincidentally we stayed with the Rialp family. Mrs. Rialp, was working for UNESCO at that time. I remembered being enamored by the vibrance of the city and the freedom of being able to walk everywhere.

“I want to live here,” said a voice in my head. The thought, for me, was selfish and unpatriotic, I never said it out loud.

Five years later, I was accepted to graduate school at New York University, a full scholarship. I planned on following my parents’ footsteps. I hoped I would meet a fellow Filipino in grad school, finish my degree, go back home, get married and start a business. What I didn’t account for is that I would fall in love with an American graduate student who had all the best qualities of my suitors back home. Shortly after I graduated, we got married in a Catholic church in Brooklyn.

“To whom much is given, much is required in return” a former suitor used to say.

When I read news about the Philippines, I am often reminded about what he said.

I have been fortunate to have been born in an upper middle class family. I was able to get a scholarship and finish graduate school and then find a stable job in the US.

What is required of me, now that I live abroad? I wonder. How do I give back?

My son and I fly to Manila to visit my parents and my sisters every other year. During each visit, I make it a point to contribute financially and volunteer at our neighborhood day care center.

It is not much, but that is what I can give for now. Maybe when my son is older and away at college, I think I can stay longer and contribute more– Do my efforts even make a difference?

I guess it will be an ongoing reckoning: What do my choices say about me? Did I do what was required? Did I sell out?

Tricia J. Capistrano’s articles have appeared in Newsweek, Mr.BellersNeighborhood.com, the Philippine Star, and TheFilam.net. She is the author of “Dingding, Ningning, Singsing and Other Fun Tagalog Words.” Her essay, “Inadequately Asian” published in this magazine, was awarded the Best Personal Essay during the 2017 Plaridel Awards held in San Francisco.