A producer, an actor, and a Rockette: FilAm representation in the entertainment industry

By Mariel PadillaReal life and fiction blur in the meta-theatre show: “KPOP,” which premiered on Sept. 5 at The A.R.T./ New York Theatres in Manhattan.

In the show, five years in the making, a cast of Asian American performers simulate the workings of a fictional K-pop factory that is working to reach the fictional American audience while an actual American audience shuffles between three stages, immersed in the parodied drama.

The show was produced by Ars Nova in association with the Ma-Yi Theatre Company and Woodshed Collective. According to Ralph Pena, producing artistic director of Ma-Yi, Broadway bought the rights for the show in September.

“It’s remarkable we have 17 Asians on stage for this show,” Pena said. “KPOP is unique because I think people are curious about what K-pop is to begin with. It’s a worldwide phenomenon so we are sort of riding on that.”

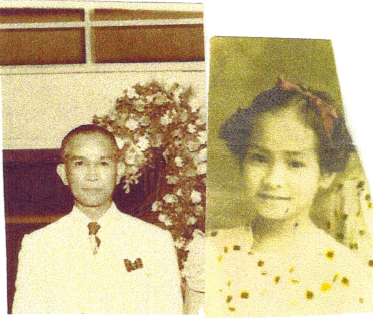

The Ma-Yi Theatre Company has seen drastic growth since its inception in 1989 when seven young Filipinos friends from the University of the Philippines started reading scripts in church basements and putting on simple shows for family and friends. “Ma-Yi” is an ancient term that the Chinese used to refer to a group of islands now known as the Philippines. The name recognizes a pre-colonized Philippines that had a culture of its own.

Twenty-eight years later, the organization has expanded as one of the largest pan-Asian theatre companies and talent incubators in the country. Ma-Yi also houses a competitive writers workshop that was established in 2003.

Nearly 90 percent of all U.S. plays produced by Asian American writers now go through Ma-Yi’s doors, according Pena, who was also one of the company’s founding members.

Filipinos are the fourth largest immigrant community in the United States, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Twelve percent of New York’s population is Asian, and yet only six percent of all available roles off-Broadway and on Broadway go to Asian American actors, according to the Asian American Performers Action Coalition.

“Theatres don’t hire Asian actors because they don’t think of Asians as actors,” Pena said.

The number of Asians in the arts is increasing, however. In the early 2000s, Ma-Yi’s founding members recognized a growing number of Asian Americans working in theatre. Pena attributes this boom to the second-generation immigrants.

“The doctors and lawyers who were forced by their parents to study medicine and law are now saying they don’t want to force their kids to do what they did. That allowed a lot of young Asian Americans to go into arts programs,” Pena said.

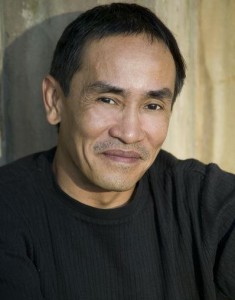

Jojo Gonzalez was one of the early members of Ma-Yi. He was a teenage television star in the Philippines before moving to the U.S., where he bussed tables and loaded docks before joining Ma-Yi.

Now, a seasoned actor, Gonzalez finished a film with Morgan Freeman and is working on a Netflix show with Emma Stone and Jonah Hill. Even now, he said it’s nearly impossible for a Filipino to find a Filipino role.

“I get the Latino calls, but I’m not Latino enough. Then I get the Asian calls, but I’m not Asian enough,” Gonzalez said, “so nobody knows what to do with me.”

Actors are not the only artists impacted by the entertainment industry’s standards. Christine Sienicki, a half-Filipino Rockette, is one of only two Asian dancers in the esteemed precision dance company.

Sienicki joined The Rockettes 16 years ago when she was only 18 years old.

“Public relations has just always really liked me because I’m ethnically ambiguous. I’m usually the one on all the posters and billboards and everything,” Sienicki said.

Her ethnic ambiguity currently makes her more marketable in Hollywood, she said. Her appeal is not in her Filipino-ness, however, but in her other-ness.

In his decades-long acting career, Gonzalez has played Latino, Thai, Korean, Japanese and Chinese characters. He only remembers playing a Filipino a handful of times.

“There are lots of Filipinos on Broadway, TV and film. We’ve always been there, but you would never know,” Gonzalez said. “I don’t think there’s been a real change in roles for us, just more surface-level effort.”

Both Gonzalez and Pena said mainstream Asian representation in the media still relies heavily on stereotypes and one-liners.

“Nurses, maids and thugs,” Pena said, “That’s what we’re portrayed as.”

When Ma-Yi was created, Pena said the founding Filipinos wanted to be more than artistic leaders. They wanted to be thought leaders and change the national conversation around ethnicity.

According to Pena, the typical audience to a Ma-Yi production is about 60 percent Asian. KPOP is an exception.

“The quality of what is put out is the most important. It also goes into the burden of the immigrant. We have to be 10 times better than others in order to get noticed,” Pena said. “A play is considered very good when The New York Times says it’s very good.”

The New York Times’ critic attended a KPOP performance on Sept. 19. The mixed review was published online by Sept. 22.

“Even in the Philippines, you need the approval of a white arbiter to be considered good,” Pena said. “So our measure of success is based on that value system, not on our own.”

© 2017 The FilAm