A deportation reality in ‘Transit’: Filipinos would rather fight it than go home

Janet and Joshua, played by Irma Adlawan and Marc Justine Alvarez, run into an Israeli police officer who asks for their immigration documents. Press photos

By Cristina DC Pastor

I watched “Transit” a day after I listened to Jose Antonio Vargas speak before a Know-your-rights forum on immigration. I didn’t plan it that way; that’s just how my schedule turned out.

But the sequence of my schedule provided a striking perspective to the 2013 film. In “Transit,” Hannah Espia’s debut film, 4-year-old Joshua recites the Torah as his father fights his deportation before Israeli police. Somehow, it reminded me of Jose and the almost electrifying way he commands his audience as he argues for immigration reform. While Joshua is fiction, and Jose is reality, they share a common truth: They live in countries that do not want them. “Transit” is like waiting for Joshua to evolve into another immigration rights activist. But it is not to be; the film had a forlorn ending.

In the film, Joshua becomes a TNT (‘tago ng tago’ or always in hiding) at a young age because Israel is trying to enforce an immigration policy of deporting children of migrant workers. The story was inspired by real events. In 2010, Israel sent home at least 1,000 minors, some of them Filipinos whose parents work in Tel Aviv as caregivers and domestic workers. Noting a sense of irony here, Israel had driven children to hiding when they themselves were frantically hiding from the Nazis in World War II.

The Filipino children spoke Hebrew, did not know anything about the Philippines, and as the Joshua character concedes, “I don’t even like adobo.” Some of them preferred to identify as Israelis because their own Filipino parents spoke disdainfully of the Philippines as a place where you cannot find a job or where children have no future.

The film, which screened on June 16 at the Museum of Modern Art, tells the despondency of two families as they fight to avoid deportation. Janet, a housekeeper, has a teenage daughter Yael, her ‘love child’ with an Israeli man. Janet’s younger brother Moises is a caregiver for the elderly. He is the father of the well-behaved but sometimes-precocious Joshua. They all share a tiny dwelling, but Moises also has a live-in quarter in the house of his kind employer Eliav. Although Yael and Joshua are born in Israel, they are in danger of being expelled because of immigration enforcement. Janet and Moises try their best to keep them under the radar. Joshua is made to wear the traditional Israeli scarf over his head to make him blend in with the locals.

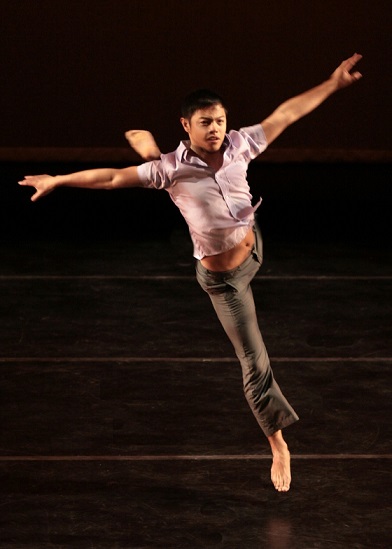

When Joshua discovers Eliav lying unconscious on the floor, he runs out into the street looking for help. A police officer spots him, thus blowing the lid off the boy’s immigration status. The scene, where Moises is tearfully pleading with the police not to deport his son, is an emotional high point, especially as Joshua recites the Torah silencing everyone in the immigration office. Young Marc Justine Alvarez, as Joshua, proved to be a promising actor – playful one minute, curiously questioning the next, but always a boy who obeys his elders.

Irma Adlawan plays Janet straightforward and exceptionally well. No irritating melodrama even as the family comes to grips with the consequences of Joshua’s illegal status. Ping Medina, as Moises, is the character in control even as he juggles multiple roles: single parent, protective family man, loving father, and conscientious caregiver. Until the law catches up with him. There is depth to his acting. Praise too for Jasmine Curtis-Smith as the teenage Yael, who believes she will not be deported because her father is Israeli. She is both rebellious and sympathetic toward her mother’s manic attempt to control her.

In the end, you come to the conclusion that immigration is the same everywhere, in Israel or in America. The laws are harsh and unforgiving, and yet Filipinos would rather cast their lot with an uncertain future than go home.

Copyright (C) 2017 The FilAm