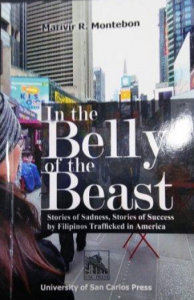

Bittersweet tales in Marivir Montebon’s book on human trafficking

Author Marivir Montebon with some of the women who shared their stories for the book, ‘In the Belly of the Beast.’ Photo by Emil Rapada

For every enslaved or trafficked immigrant that Marivir Montebon has painstakingly given a permanent voice in her book, “In the Belly of the Beast,” there are probably a hundred equally tragic secrets taken to the graves.

Immigrants’ laments are at times only talked about behind closed doors or even denied by the victims themselves. For every trafficked person who made it to the United States, there are perhaps more who only made it halfway. Some spent a fortune or wanted to leave everything behind but miserably failed but they are still willing to risk life and limb for the promise of a better life. I have to say that risk-taking is in our genes.

Unlike continental peoples (Africans, most Europeans and mainland Asians), we, islanders, did not just walk to get to where we are. Our ancestors paddled their way to the Philippines and to the remotest islands on earth. From the Eurasian landmass, they started their unheralded journey not knowing if there was even a hospitable land beyond the horizon.

In this book, Marivir does not only boldly and capably take us to the dark side of human migration but also makes us reflect on our own bittersweet immigrant tales.

We all can relate to every minute detail Marivir has documented in her trailblazing book about trafficked persons – the thrill of setting foot in another country, the tears that separation brings, and the things we can finally have that we can only see in the movies.

Being a people consigned to the periphery by the gods of money, the travel money that we all have to raise could amount to months or even years of earnings, trafficked or not.

Who is not familiar with waiting many years before being reunited with family members because getting a visa — whereas automatic for some nationals — is as rare as winning the lottery. Not being able to attend funerals or visit a sick parent or child is an all-too-familiar story.

I’m beginning to ask if we are a trafficked nation as a whole. In some sense, we still are.

What makes Marivir’s book special after I read it is it made ask myself what can I do to help stop human trafficking. This book is not your ordinary art for art’s sake stuff. It’s a call to action.

The crusade begins within each of us. If we all lived simply content with small dwelling, home-cooked food, radio instead of big TV, hand-me downs instead of signature clothing, vegetable garden instead of canned foods, raising farm animals instead of pigging out often, etc., maybe there will be one less trafficked mother of young children. That’s one great triumph over one evil trafficker.

Of course, strict laws, educational programs and sound economics have to be implemented. That I have to leave to the experts.

Thank you, Marivir, for your courage and for putting to good use your talent toward higher good.

Pol Tiongson is a dermatology specialist with offices in San Jose, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, California.