After 4 decades in China, Jaime FlorCruz is almost ready with his book

The former CNN bureau chief learned Mandarin from working in a state farm and later a fishing village. CNN photo

He spoke perfect Tagalog in dulcet tones I have not heard of in a very long time since my Bulacan-born father passed away in 2007. That was my first impression of Jaime FlorCruz, CNN’s former Beijing bureau chief, when we met for drinks at a laid-back bar on West 39th.

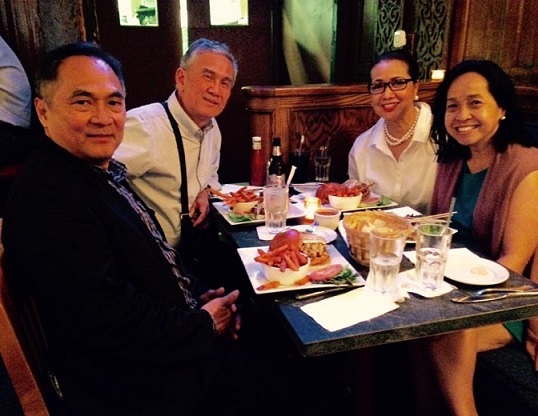

He comes from Malolos, Bulacan, that’s why, he told his audience of close friends, Jojo de Jesus and Suzie David, and one fascinated journalist. I have heard of Jimi’s exceptional accomplishment, visiting China in 1971 and never leaving until he was a well-regarded journalist more than 40 years later. I never met him, until last week.

The China Chapter came in the course of drinks and conversation about Philippine politics, traffic, and retirement. When his story unfolded, it’s as if we were hypnotized.

It began with his mother pacing his room, vacillating whether or not to wake him up so he could get to the airport to catch his plane to China. It was the morning of August 20, 1971.

“I didn’t know about it then,” he said. “I just found out seven years later when she told me. In the end she decided to wake me up because she knew I wanted to go to China.”

Jimi – then an Advertising student at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines — and 14 other student activists had been invited for a three-week study tour of the People’s Republic of China. It was a trip every Mao-inspired radical at that time may have dreamed of. In the evening of August 21, 1971, the Plaza Miranda bombing erupted.

The delegation disembarked in Hong Kong and were transported to China by the backdoor. The Philippines, like many countries at the time, had no diplomatic relations with the communist China so the hosts made sure the passports carried no official stamp of arrival.

Manila was thrown into political tumult following the Plaza Miranda bombing that killed 9 people and wounded almost a hundred including politicians from the Liberal Party. The writ of habeas corpus was suspended, an act indicating the country was in a state of rebellion. The students, all aching to go home, waited until the political situation simmered down. It did not. A year later, Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law.

While they were treated well – provided meals and lodging — by their hosts, being separated from family was not something they were prepared for.

“Our hosts said we could stay for as long as we want and could leave anytime; they will prepare our travel documents,” he said.

The prospect of going home dimmed, although 10 of the students took a chance and returned. Jimi and four others – Ericson Baculinao, Grace Punongbayan, Chito Sta. Romana, and Rey Tiquia — stayed behind. It was, for them, a time of deep worry and uncertainty. Blacklisted by their government, they knew they would be arrested on their return.

The five were getting bored and homesick. They wanted to do something productive with their time and not just “sleep and eat.” They wanted to study, but the schools during the time of the Cultural Revolution were not open to foreigners. Young and full of energy, they decided to get a job. Jimi was then 20 years old.

They worked on a farm in Hunan, from 1971 to 1972, a province known for its spicy food and nasty weather. They earned little money but received training in Chinese language after work. It was not an ideal condition, but to Jimi the “romantic” notion of being part of China’s working-class was a matter of survival. They worked in a fishing village in Shandong province until 1974 and continued their Chinese lessons.

“That’s how I learned how to speak and write Chinese,” he said.

Jimi enrolled at Peking University in 1977, earning a degree in Chinese history after four years. The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and the collapse of the Cultural Revolution paved the way for China, then ruled by Deng Xiao Ping, to slowly open up to foreigners. American companies, including media organizations, began to set up offices in Beijing. Jimi and his fellow Filipino exiles – who spoke Mandarin and were proficient in English — were local talent just waiting for the right opportunity.

He heard about an opening for a translator at Newsweek magazine in 1980. He was not too enamored with working for an American company, still holding on to his ‘anti-imperialist’ viewpoint. But his friends were quite happy with their jobs, and so he gave it a try. His work was tedious but relatively easy: clipping newspaper articles about China. His break as a reporter came when he was sent to cover the trial of the Gang of Four, the communist leaders who attempted to seize power after Mao died.

“I would be there in front of television every day watching the coverage of court trials in Chinese,” he said. “Those were long hours in court.”

He moved to TIME magazine in early 1982 and became its bureau chief in 1990 after Sandra Burton, the last journalist to interview Ninoy Aquino before his assassination, retired.

“She loved the Philippines and the people,” he said. “She encouraged me to take the position.”

He joined CNN where he was thrust before cameras as a live reporter and Beijing specialist. He retired as bureau chief in 2014 having achieved the distinction of being the “longest-serving foreign correspondent in China.”

Jimi is currently completing his memoir about his time at Peking University where he met and became friends with some of the most important Chinese politicians and world leaders. The title of his book to be published by Penguin China: “Class of 1977.”