Cherie Gil: Artist in a hurry

By Joel David

There will always be ambivalence surrounding the Filipino word for performer: artista. The word it suggests in English is in many ways opposed to the notion of an artist, standing apart from issues of popularity and financial success. This is why the first film star recognized as National Artist, Nora Aunor, underwent such a difficult process that two successive final rounds regarded her omission as no big shakes.

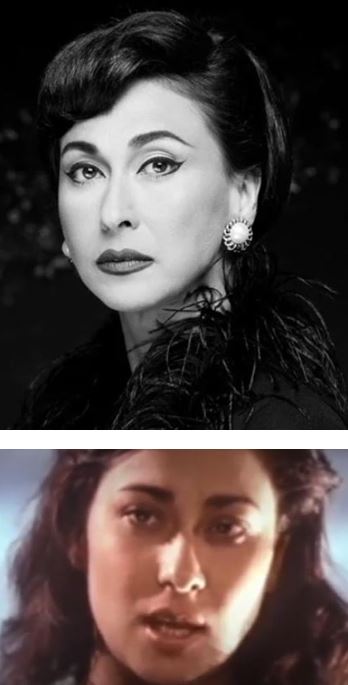

Cherie Gil, who died before she could turn 60, started as a star, became an active and reliable supporting actress, left the country to attend to her family, and returned when she found she wasn’t cut out to be the wife of Rony Rogoff, a globally renowned violinist. When news of her death broke recently, folks in my limited netizen circle were as shocked as I was that she was already more than the sum of everything she was before she first departed, during the preceding millennium. Gil belonged to the renowned Eigenmann clan of performers, where ironically only her parents and elder sibling, Michael de Mesa, remain after another brother, Mark Gil, passed away in 2014; both were admirably stoical about keeping their illnesses private.

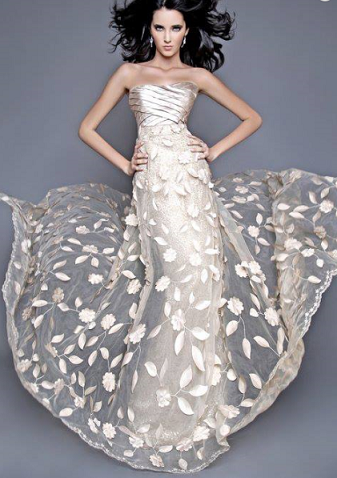

Before her mother, Rosemarie Gil, retired from acting, production projects that required a good-looking villainess only needed to decide whether she should be older or younger, then contact the Eigenmanns. Cherie Gil’s film appearances since her comeback were authoritative owing to a renewed seriousness, and radiant from the loveliness endowed by her mixed-race heritage; she opted to teach acting and study scriptwriting, signs of a restlessness of spirit; she produced her own dream project, a reworking of an earlier prestige project titled Oro, Plata, Mata (1982) with the same director, Peque Gallaga, in tandem with Lore Reyes.

Sonata, her 2013 Gallaga-Reyes production, brandishes what on paper might seem like a fantasy figure: an opera diva traumatized by losing her voice, who returns to her rural estate and learns to overcome her reclusive state by taking an interest in the several munchkins who hang around the place. Only someone who underwent an equivalent process in real life and resolved to heal her heartbreak by plunging into artistic fulfillment would be able to display the full measure that the character required, and we will always be fortunate that Gil was exactly already that person. She had portrayed a similar role onstage a few years earlier, as an elderly Maria Callas in Terrence McNally’s Master Class.

It was these theatrical forays of hers that the local cognoscenti looked forward to, and Gil accommodated the offers whenever she could. The mass audience still had some catching up to do, but her pre-departure appearances proved iconic to different kinds of people. Her role as lesbian drug dealer Kano in Ishmael Bernal’s Manila by Night (1980) combined a tough exterior with a movingly self-destructive faith in true love, while her performance in Bilanggo sa Dilim (1986), Mike de Leon’s exceptional video adaptation of John Fowler’s 1963 novel The Collector, presaged her triumphant collaboration with the same director’s Citizen Jake (2018), where she demonstrated how malignant damage could be delineated with a minimum of speech and gestures.

It was her premillennial turn as nasty celeb Lavinia Arguelles, won over eventually by the humility of Sharon Cuneta’s loyal fandom in Bituing Walang Ningning (1985), that inspired generations of drag queens to memorize her single-sentence fulmination, glass of cold water at the ready. Cuneta posted the bittersweet farewell she was able to have with Gil in person – which led to the heavier realization that descended on observers: these were two chums who were able to mature together, in parallel but impressive ways, so we thought it may only be a matter of time before Gil could persuade her BFF to explore the legitimate stage together.

That, and many other potential treats, will now only have to be relegated to the realm of speculation forever. But the lesson that Gil modeled for her generation of pop-culture jobholders abides: that one can always upgrade one’s craft, and in so doing, leave this world a better place even ahead of schedule. Politicians will always make their self-serving claims and will die off in time, but real art is what will always be worth treasuring.

Joel David is a professor of Cultural Studies at Inha University and was given the Art Nurturing Prize at the 2016 FACINE International Film Festival in San Francisco. He has written several books on Philippine cinema and maintains a blog at https://amauteurish.com.

(C) The FilAm 2022