NUT to film critics: ‘Don’t take things too seriously’

By Joel David

When I started looking out for bylines of prolific Filipino writers in English, Nestor U. Torre’s was the one I wound up reading most often. When martial law was declared, he moved from the opposition’s shuttered Manila Chronicle to the Philippines Daily Express, edited by a brother of the First Lady. Yet this was the period of the ascendancy of Torre (or NUT as he preferred to refer to himself) as film commentator. He was also known as the director-writer of Crush Ko si Sir (1971), a pre-ML vehicle for Lino Brocka’s muse Hilda Koronel.

Not enough focus was placed then on NUT’s film writing, just as it was relegated at present to the background in nearly all the tributes paid to him by his colleagues in theater. This was the moment when film was setting out to stake its claim as a creative activity worth taking seriously. Most reviewers, then as now, claimed academic credentials and wrote accordingly. But like Bernal, NUT stepped in from an immersion in pop culture. Academia eventually came around to valorizing that kind of orientation, but it was too late for NUT.

He wrote film reviews in a breezy, amused, occasionally ironic, sometimes self-deprecating manner, in a style that serious students of English literature would recognize as highly accomplished. When a NUT review appeared in the Express, some of my classmates and professors would engage in discussion about it. I remember a senior stating that his take on Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) was better than what came out in foreign newspapers – so I did spend some time afterward at the national university’s main library to confirm the claim. Around this time an announcement involving NUT came out, one that I was still too young to realize was ominous: he and the other reviewers published by the Express were forming a critics’ organization, with him as founding chair.

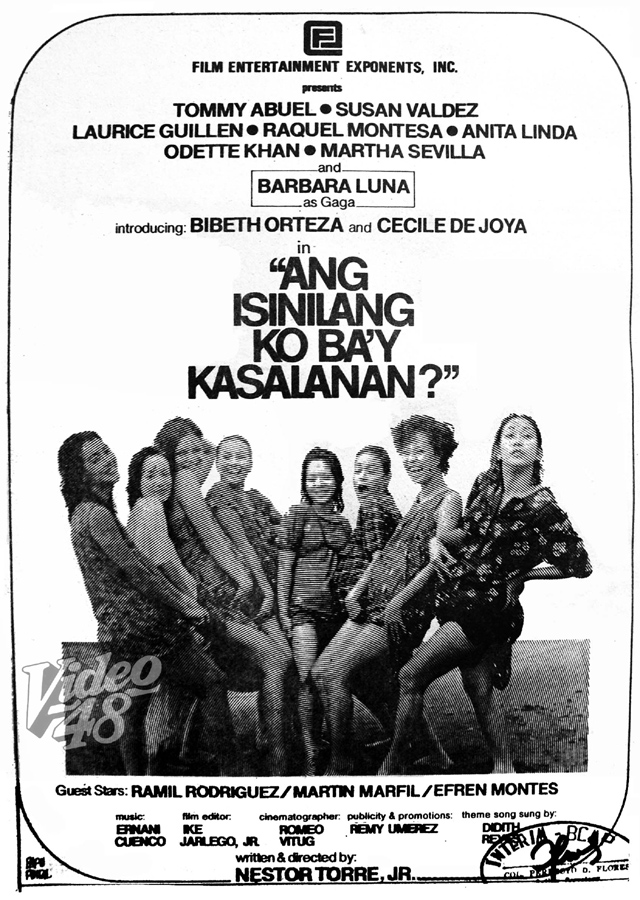

I subsequently became a member of this group, the Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino, which was how I learned about NUT’s departure. He was able to work on his last film project, Ang Isinilang Ko Ba’y Kasalanan? (1977), the year after the group launched its still-ongoing annual awards. At the meeting where it was discussed, the other members raised questions pertaining to its lack of political content and its derivative quality. He walked out and never showed up again.

The MPP prided itself on objectivity and admitted being harsher on its own members who aspired to industry practice. NUT’s misfortune was that he was the first to be subjected to this type of critical interrogation; ironically another founding member, Behn Cervantes, released Sakada during the year of the MPP’s founding. It had enough so-called social relevance to be considered subversive and was eventually banned by the government. Not surprisingly, it elicited rave reviews from the MPP members and was able to receive citations in major film categories, though its later unavailability excluded it from the awards competition.

Another MPP member, Pio de Castro III, came up with Soltero in 1984 and was rewarded with nominations from the group for direction, performance, and technical categories. Yet although AIKBK was completely bypassed, it had qualities that placed it a cut above the other two films: it featured eight women at a well-known halfway house for unwed mothers-to-be, and although the narrative finally gave precedence to the male superintendent empathizing with the expectant mothers, several of the individual stories succeeded in focusing attention on the plight of outcast women.

I remember AIKBK coming out a few months after a Brocka film which had almost the same number of female characters, but which more easily capitulated to the central tale of a son seeking his mother and discovering how she worked as a has-been hooker in Olongapo. Unfortunately, these last two films may be lost for good, so we have no way of revaluating the merits of NUT’s entry vis-à-vis the others. All I can attest, to the best of my recollection, is that it left a far stronger impression than all the other films made by NUT’s MPP colleagues.

I had only one interaction with NUT, years after he gave up “creative” film activities including his distinctive brand of film reviewing. We were covering a 1980s film troubled by serious conflicts on set. Upon arriving, he immediately launched into a parodic performance of film buffery: he would mention an obscure decades-old movie title and state what its opening-day gross was, then he would start mentioning bit players no one ever heard of, as well as running times of ancient films no one had seen. “Isn’t it great to waste everyone’s time with information no one will ever need?” he went.

I later asked him what he thought film critics should be doing if they wanted to make a positive contribution. “Make sure to connect,” he said, “and don’t take things too seriously.” Bibeth Orteza, whom I remember made the strongest impression in AIKBK, once mentioned that NUT was determined to compile an anthology of his film articles. This was before he had his stroke in 2018, after which his mother died, he contracted Covid-19, and passed away last April 6, at 78. He was determined to recover from his stroke, but got exposed to the virus via his physiotherapy program. He will be remembered for several accomplishments like public relations and theater activities, but not for far more significant ones.

Joel David is a Professor of Cultural Studies at Inha University and was founding Director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute. He was given the Art Nurturing Prize at the 2016 FACINE International Film Festival in San Francisco and is this year’s recipient of the Writers Union of the Philippines’ Balagtas Award for Film Criticism. He has written several books on Philippine cinema and maintains a blog, Amauteurish, at https://amauteurish.com.