I hope this country will finally call Jose Antonio Vargas what he is: an American

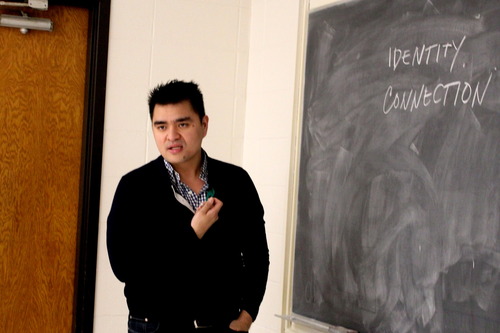

By Laurel FantauzzoOn July 15, the storyteller Jose Antonio Vargas was detained at the McAllen, Texas airport for not having a valid entry visa in his Philippine passport for the United States.

Last year, Jose visited my nonfiction writing class at the University of Iowa to talk about his journey to a Pulitzer Prize. My students asked him about his thoughts on race, how he ended up at The Washington Post, what it was like to write for The New Yorker, his pivotal friendship with Mark Zuckerberg, his coming out as gay, his coming out as an undocumented immigrant, and what his plan would be, should he be detained by authorities.

He was frank, funny, passionate, and had a tremendously strong hold on his message: that immigration reform in the U.S. was long overdue, and much deserved by many souls in this country.

My students and I had the sense that Jose was embodying his own story in a particularly intense way. He said two principles guided the core of his work: identity and connection.

I observed that he had placed his own immigrant body on the line for one of the great American injustices of our time. He hoped that his openness about his own journey might bring empathy to so many others living out similar stories within, and around, American borders.

When I met Jose, he felt to me like someone who could be a cousin, or a friend, if his frantic schedule would ever allow for it. When I met him at KRUI, the University of Iowa’s radio station, Jose asked me, “Pilipina ka ba?” with a familial grin, and I replied, in my childlike Filipino, “Opo. At gay din!” (Yep, I’m Filipina. And gay, too!) I, too, have relatives who were forced to make a life here without documents.

Like hundreds of thousands of other Americans, I follow his journey on Twitter. Both of us hold James Baldwin up as a writer’s oracle. But whenever Jose posted, I paid special notice to any tweets about his longing for love and relationship. I thought that he had already done great professional work, and that, in any case, he deserved loving company.

Of course, Jose is going to continue to work as long as he can, in the legal limbo that he lives, in the home he has chosen to love. And James Baldwin continues to haunt and guide him.

What we feared for Jose—an unjust detention—has, for the moment, come to pass.

I do not hope to reunite with Jose in the Philippines in this way. I hope that the country he loves and claims will behave in a humane way toward him. I hope this country will finally call him what he is: an American.

We await the further unfolding of his story, we stand with him, and we continue to pray for his heart.

This essay original appeared in the author’s blog laurelfantauzzo.com, and is being republished with permission. Jose Antonio Vargas has been released after about eight hours.

As a gesture of goodwill the Philippines may want to reform it’s own immigration law. In the Philippines overstayers must pay fines. Anyone who overstay more than 18 months will be jailed and will be deported. Staying in the Philippines is a “privilege” and not a right. Many foreigners end up being jailed and kicked out the country on false charges. The system makes foreigners very vulnerable. If anyone interested about the ugly truth about Philippine Immigration Law may want to watch Alfred Lerner interviews on Youtube.