Remembering Pepe Diokno and his crusade against corruption

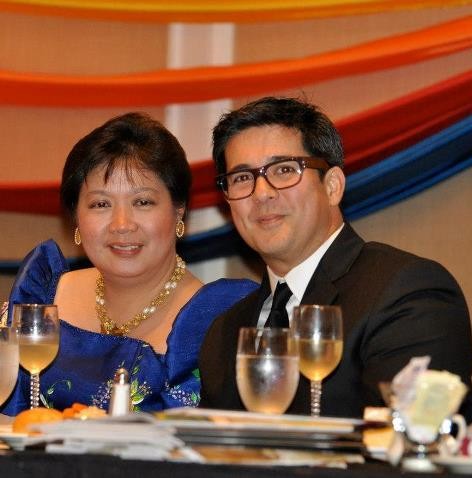

Diokno, with Cory Aquino in the ‘80s, fighting the dictatorship. Note breast pocket with a message for Ferdinand Marcos. Photos: Diokno.org

By Tony Joaquin

The two men, unusually well-dressed in dark suits in a typically warm Manila evening, were ushered into the lobby of the house by the maid. They asked to see the American master of the house. The maid motioned them to take a seat in the plush receiving room in Dasmariñas Village, Manila. They smiled but remained standing.

Inside were men playing poker. Upon learning of the guests, the American, cigar in hand and apparently affected by whisky in his masterly voice, ordered the maid to escort the two men into their poker room where the players were all Filipinos of stature – from the upper level of government and private business.

Smartly in their suits the men appeared and stopped a few feet from where the men were enjoying their poker game.

“What can I do for you, gentlemen? Asked the American as he took a puff from his cigar.

“Mr. Stonehill,” stated one who was probably a senior of the two in rank, “We came to arrest you and we have the warrant with us.”

Taken aback he guffawed while the others echoed his forced laughter. “Who sent you? Pepe?” asked the American. Summarily Stonehill ordered his secretary to phone Pepe Diokno, secretary of Justice and added “use his direct line?”

The other man hastily interrupted. “Sir, Secretary Diokno issued the warrant of arrest.”

Silence. “Sir, you are under arrest and you must come with us this minute. Please dress up quickly.”

With complete and obvious puzzlement in the American’s face, drained of blood, unable to utter anything, he disappeared to change into his street clothes. The two men led Harry Stonehill, before his surprised guests – politicians, law enforcement officers, businessmen, wheeler-dealers all – out of the house and into detention at the NBI office on Taft Avenue.

That was the last time Harry Stonehill ever saw his residence. Soon after, Harry Stonehill was deported and declared persona non grata by the Philippine government. He never came back to the Philippines until his death sometime in the late ‘90s.

For many years after World War II, the seeds of corruption had begun to grow permeating the middle and upper echelons of Philippine society. Stonehill, ever the sharp Jew knew how to handle the Filipino businessmen and government officials. In no time, Stonehill had diversified his operations in the Philippines to glass, cotton, oil, insurance, newspaper publishing, cement, real estate, land reclamation which all resulted in a multimillion dollar conglomerate with property in eight countries and a personal fortune of $50 million (at the time the exchange was P2 to $1 dollar.)

Like Ferdinand Marcos who early in his political life knew the weakness of fellow politicians, Stonehill had virtually most powerful government officials in the Senate, Justice department and the business sector “in his pocket.” Except one. Jose Wright Diokno. As a matter of fact, many of the sad value systems that ruled crooked politicians then still prevail in the Philippines of today – “you can get anything you want in the Philippines…anything…if you know who to see” — still rings true, sad to say.

Harry Stonehill was a young American Army lieutenant who saw the vast possibilities in the Manila of 1945. Following his discharge, he dumped his American wife and child and returned to Manila alone. Together with Marcos, both found common interests and value systems but became silent partners. His job was to introduce leaf tobacco cultivation to the Ilocos, Marcos’ home province. In 1950, Stonehill linked with another partner in the person of Peter Lim, a member of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines. Their gimmick was to buy cheap inferior tobacco and sell it to the Philippine government at bright leaf prices. Soon the tobacco monopoly found itself with a lot of high prices trash. Many cigarette manufacturers in the Philippines lost their leverage and had to close down. Stonehill’s profits were smuggled out through devious channels to secret numbered accounts in Switzerland. Once, Harry Stonehill was overheard saying that he can do anything that he wanted by hook or by crook because “everyone has a price.”

He was right. But in those dark days, there still were virtuous men in the government, and one of the prominent ones who was not “in Stonehill’s pocket” was Jose Wright Diokno, who as secretary of justice and even among Stonehill’s’ acquaintances, had to do his duty. And he had to enforce the law. Diokno, or “Ka Pepe,” as he was popularly known, was born on Feb. 26, 1922, to Ramon Diokno, a former associate justice of the Supreme Court, and Eleanor Wright, an American who became a Filipino citizen.

He graduated from elementary school with distinction, and finished his secondary education at De La Salle College as valedictorian in 1937. In 1940, he earned his bachelor’s degree in commerce summa cum laude also at La Salle. He topped the CPA board examination in the same year with a rating of 81.18 percent. In 1944, without finishing his bachelor of laws degree, he took and topped the bar examination, with a rating of 95.3 percent. In 1961, President Diosdado Macapagal appointed him secretary of justice.

Diokno believed in the sacredness and dignity of the human personality. Diokno was again voted outstanding senator in 1969 and 1970, thus earning the distinction of being the only senator so honored for four consecutive years beginning in 1967.

At that time, President Marcos was bending toward dictatorship in preparation for the declaration of martial law. Diokno, seeing the increase in human rights violations in the Marcos regime, bolted from the Nacionalista Party in the early part of 1972. His crusade for human rights so irked Marcos that when martial law was finally declared on September 21, he was the first member of the opposition to be arrested. He was imprisoned without any charges being filed against him. Upon his release in 1974, Diokno immediately organized the Free Legal Assistance Group, which gave free legal services to the victims of military oppression under martial law.

From the time he was released from prison, Diokno fearlessly, and with grim determination, fought for the restoration of Philippine democracy. He was a towering figure in opposition rallies denouncing the Marcos regime from 1974 up to the “Edsa Revolution” in February 1986. During the incarceration of Ninoy Aquino, Diokno was in constant contact with him through his wife Cory Aquino, who acted as confidant of the two foremost oppositionists of the Marcos regime.

After the Edsa Revolution, President Corazon C. Aquino appointed him chairman of the Presidential Committee on Human Rights, with the rank of minister, and chairman of the government panel which tried to negotiate for the return of rebel forces to the folds of the law. However, after the “Mendiola massacre” of Jan. 22, 1987, where 15 farmers died during an otherwise peaceful rally, Diokno resigned from his two government posts in protest of what he called “wanton disregard” of human lives.

At 2:40 a.m., on Feb. 26, 1987, Diokno died nearly on the same date he was born. The cause of his death was “acute respiratory failure due to cancer.”

Diokno was married to the former Carmen Icasiano, with whom he has 10 children: Carmen Leonor, Jose Ramon, Maria de la Paz, Maria Serena, Maria Teresa, Maria Socorro, Jose Miguel, Jose Manuel, Maria Victoria, and Martin Jose.

Tony Joaquin was a television producer, director, newspaper journalist, industrial trainer and soap opera actor in the Philippines. He still gets excited by new ideas, films, love and living. He is 81.

I am now following your blog regularly. Thanks a lot for the wonderful articles.