How the Filipino ‘mangkukulam’ found its way into American horror fiction

By Daphne Fama

“When your grandmother was pregnant with your mom, I spent all night with a bolo, ready to cut the tongue off of any aswang who wanted to eat your mom up,” my grandfather once told me, his smile both teasing and proud.

Carigara, the little town where my family had spent generations, was full of creatures and dangers like that. And my grandparents and cousins were thrilled to scare me—their small Americana cousin—each year I came to visit.

That’s simply how my family was. Playful and a little rough but utterly accepting of me as I fumbled through a world that was only half mine. They taught me to respond to compliments with ‘buyag’ and whisper “tabi tabi po” when we passed by duwende hills.

Eventually, my grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins would come with me back home, to the rural United States. Our backwater town was a stark contrast to the warm and social barangay they’d left behind. So, we cobbled together a little Carigara. A home away from home. But even between tobacco fields and the choir of cicadas, they still filled my head with superstitions and strange creatures. As I grew older, the stories they gave me grew a little darker. Engkanto-driven suicides, minds lost to spiritual madness, possessions and ghosts.

From a young age, I wanted to write every one of those stories down. In large part because I could see them fading before my eyes as urbanization rolled through the Philippines and began to root itself in rural villages. Stories of ‘sigbin’ and ‘wak-wak’ were dismissed, superstitions forgotten.

“If I ever get really rich,” I told my mother, “I want to be a Filipino folklorist. I don’t want all those beliefs to be forgotten.”

She laughed and told me to wait until I became a lawyer and then retire—then I could do whatever I wanted. I did half of what she asked me to do. I became a lawyer but quickly realized just how soul crushing fluorescent lights, pencil skirts, and unchecked egos could be.

And so, I began to write. I wrote stories I was sure only I wanted to read. The first was an utter disaster—a Filipino dystopic sci-fi that integrated gods from each of the three hearts of the Philippines. I knew the second would weave in the superstitions, monsters, and magic I’d learned from my family and a ‘mangkukulam.’

But after seeing Bongbong Marcos hit the political stage and become president, my plans accelerated. My mother and grandparents had told me just how brutal the time beneath Marcos was. A board dedicated to getting victims reparations estimated that there’d been 3,000 extrajudicial killings, 35,000 cases of torture, and 70,000 jailed without due process. I was furious that something that had happened in living memory was being whitewashed—even members of my family who had denounced Marcos a few years ago were now backtracking.

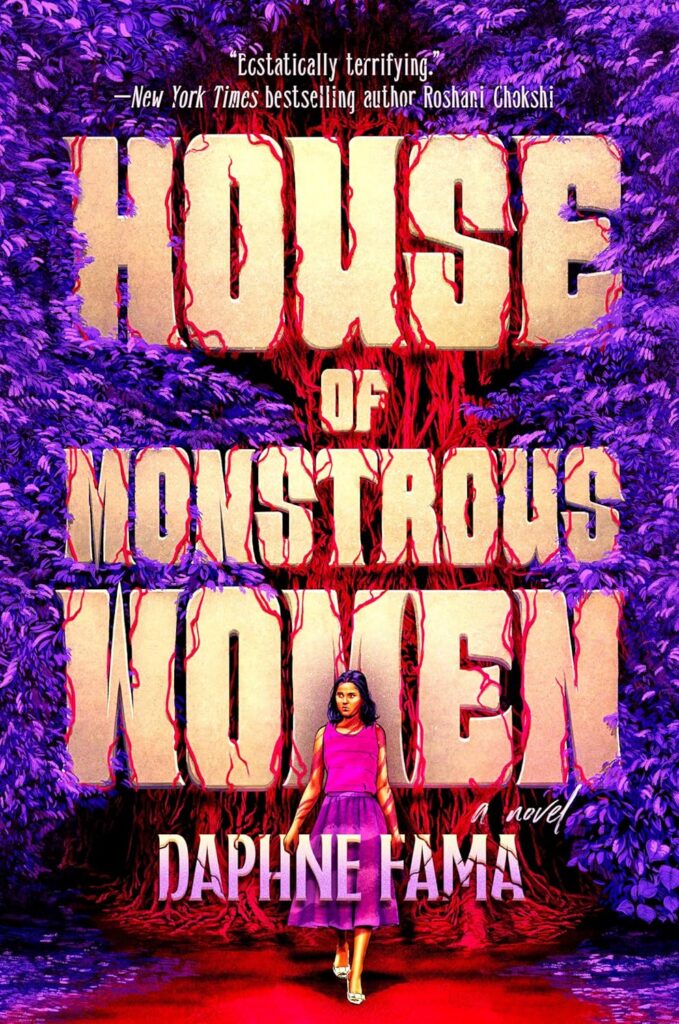

“House of Monstrous Women” then began to form. I wanted to bring back light some of the pain Marcos had caused while emphasizing the risk, hope, and tenacity of the people who fought back against him.

It might be bold to say that the People Power Revolution is one of the most inspiring moments of human strength in modern history, though I’m happy to say it here. People came armed with rosaries, flowers, and signs to face down tanks and guns. They believed in a better future and came together to make it. It’s something that should never be forgotten.

“House of Monstrous Women” is a culmination of so many things. It is a love letter to a Carigara that no longer exists, to folklore shared only by word of mouth, to the people that stood against a seemingly unbeatable threat and won.