Bold in heaven: Jaclyn Jose, 60

By Joel David

With the announcement of Jaclyn Jose’s sudden demise last March 2, a significant number of mostly middle-aged Filipino film observers were stunned to realize that, in keeping aware of her, a full, challenging, and ultimately triumphant life became their privilege to witness. Even the trajectory of her physical appearance, from anxious young waif to authoritative full-bodied matron, bespoke a life conducted at peak critical tension, constantly in search of solutions to creative challenges and grateful to be afforded the opportunity to find fulfillment in a specialized type of stardom where her work discipline and moral integrity ensured that she would have next to no rivals whatsoever.

She was of course intelligent enough to realize from the start that “bold star” status was a title that most women anywhere would find unappealing, if not appalling. But having been born in poverty, and realizing that sex-film production was in full blast because of the Marcos (Sr.) regime’s desperation in looking for ways to discourage mass participation in the burgeoning anti-dictatorship movement, she realized that this was a unique opportunity that might never come her way again.

In a remarkable interview with Ricky Lee, who was writing a number of screenplays for her, she foregrounded the debates her professional self was having with her religious background. (Titled “Walang Bold sa Langit” or “Bold Not Allowed in Heaven,” the piece was reprinted in a number of Philippine outlets as a tribute to her.) She admitted, among other things, that she was hoping to compensate for what she considered were transgressions, by performing the standard penance of good work.

In fact, she was already overcompensating even that early. William Pascual, who directed her in the ensemble “Chikas,” picked her out to star in the superior chamber piece “Takaw Tukso,” where she outshone the then-best available names for a crime-of-passion melodrama. She achieved the same feat of upstaging more established actors in “White Slavery” – which happened to be directed by Lino Brocka, who consequently made sure that she would be the sole female lead in “Macho Dancer.” Chito S. Roño’s debut, “Private Show,” showcased what was arguably the most challenging “bold” role possible, that of a live-sex performer, which another star, Sarsi Emmanuelle, had already made definitive in Tikoy Aguiluz’s “Boatman.”

“Private Show” was railroaded by the February 1986 people power uprising, since it was the type of extreme sample that could only be screened in the Marcoses’ censorship-exempt venue, the Manila Film Center. More than any of Jose’s earlier work, it contained passages that were also bold in the sense of being expressionist and experimental; when Roño (still with Lee scripting) decided to unfold a diptych with “Curacha: Ang Babaeng Walang Pahinga,” he cast the post-Marcos era’s top sex siren, Rosanna Roces, but he also provided a climactic moment where Jose’s character reappeared to suggest solidarity – not just between two generations of live-sex characters, but also between the best bold stars of their time.

As she had correctly anticipated, roles that featured the character types she specialized in quickly dwindled. Nevertheless Jose had enough acclaim and acting trophies to ensure that she could still be cast in supporting roles, usually as the lead actor’s mistress or lead actress’s best friend. At this stage, she apparently had another round of figuring out (complemented by an intensive theater experience, in Lee’s “Pitik-Bulag sa Buwan ng Pebrero”), and arrived at a workable solution: for minor roles, she would attempt a consistently affectless delivery, then let loose at peak level wherever the character had a dramatic opportunity, usually in her final scene. The approach served to remind audiences and colleagues that she remained a talent who refused to be taken for granted.

With the emergence of digital technology and streaming services in the new millennium, Jose was able to secure greater opportunities in her career path. She could once more land an occasional lead role, and explore her potential for class-parodic comedy in TV series. The lesson she provided as exemplar was undeniable to anyone who bothered to take stock: one may already have the rare fortune of emerging fully formed, but longevity can only be attained through hard work, in her case in both analytic and physical terms. From this perspective, her Cannes Film Festival prize merely affirms what Filipino audiences already realized and admired about her through several decades of familiarity.

The few instances where she mentioned feeling abandoned should not be conflated with the tragic circumstances of her death from a bad fall when no one was present to check on her well-being. She’d always known that life would be hard, and that the pursuit of artistic excellence will always be a lonely undertaking. Her initial appearance reminded observers, no doubt including Brocka, of a talented predecessor, Claudia Zobel, who died in a horrific car accident – as Brocka also would a few years later; two other waifish bold stars, Pepsi Paloma and Stella Strada, died by their own hands at the time when Jose was contending with a decline in film assignments. One might wish she lived longer than she did, but we could just as well marvel at how she managed to thrive as long as she had.

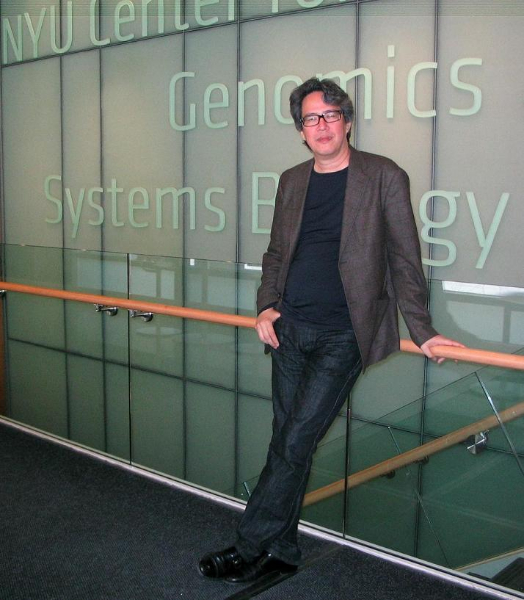

Joel David is a retired professor of Cultural Studies at Inha University and was given the Art Nurturing Prize at the 2016 FACINE International Film Festival in San Francisco. He has written several books on Philippine cinema and maintains a blog at amauteurish.com.