A historically obscure war

August 2011

Bloomsbury Press

320 pages

By Allen Gaborro

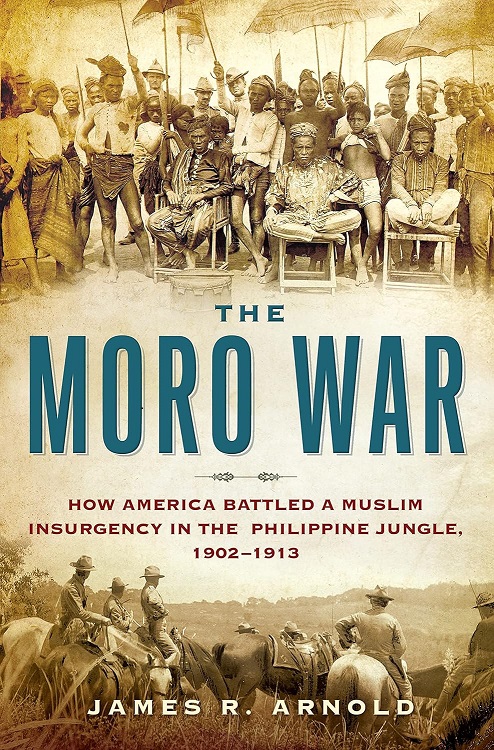

James R. Arnold’s book, “The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913,” turns our attention to a historically-obscure war, obscured by studies done in the service of elitist and colonial interests.

That war was the Philippine-American War of colonization (1899-1902). In the aftermath of that war arose a more localized but equally intense conflict between the American colonizers and the Muslim or “Moro” rebels in the southern Philippines. The so-called Moro War persisted for 11 years from 1902 to 1913. It would be the first time that the United States fought against Muslim combatants on anything resembling a large scale.

The Muslim regions of the southern Philippines were an alien commodity to the new imperialists. As Arnold writes, “To the Americans, Moroland was a strange place occupied by fierce Islamic warriors and primitive, pagan hill tribes.”

Arnold explains that “The brutal suppression of the Filipino insurgency in 1902 seemed to offer a chance to begin anew America’s first social experiment as a colonial power in Asia. Overlooked was any notion that a decade-long war in a place called Moroland was just beginning.”

The Moro war drew the attention of both opponents and proponents in the United States. In the U.S. at the turn of the century, there was a concentrated stream of anti-imperialist disapprobation of the use of force to suppress the Moros. That was counterbalanced by those Americans who favored an approach that was underpinned by a more barbed demonstration of power.

It occurs to Arnold that the Americans were more benign colonizers as compared to the abusive Spanish. A point in fact is that the Americans had no intentions of forcing the Moros to turn into Islamic apostates and become Christians.

The United States, as Arnold and other colonial apologists in their glass-half-full perspective of foreign rule like to interpret, was not out to conquer the Morolands (which comprised the large island of Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago, and other nearby territories) so much as it was to construct within them. Construct in full effect a civilization that was vividly drawn as one that would correspond to the larger Christian society in the Philippines.

However, by attempting to append the Moros to the wider Christian society, the Americans would leap from the frying pan of Moro suspicion and enmity into the fire of a Muslim insurgency. When it came to introducing a Western style of government and society to the Moros, the Americans failed to reconcile these goals with Islamic scripture.

This helped to convince the Moros that the American colonizers and non-Christian Filipinos were out to snooker them out of their religion and thus, out of their traditional lands and way of life. Pushed outside of their socio-religious and cultural comfort zones, the Moros responded with aggression.

Thinking that they could deal a quick, crushing blow to the Moro fighters, the U.S. military learned an abject lesson reminiscent of its experiences decades later in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In battling a technologically-inferior but determined adversary that could not be dissuaded or intimidated from defending its land against a foreign incursion, the Americans, as well as the Moros themselves, suffered severe casualties during their conflict.

James R. Arnold deserves congratulations for recounting the story of America’s war with the Moros, for it is a war that barely registers in the American and even Filipino historical consciousnesses. It is a war that bears in more than one way a cautionary resemblance to America’s military struggles in the future.

“Moro War” is also a valuable extant record of the Filipino Muslim identity, in its varied manifestations, and the reality of colonial expansionism and the indigenous postcolonial reaction to it.

Support independent bookstores! Bookshop is an online bookstore with a mission to financially support local, independent bookstores. Below is a link to TheFilam.net Bookshop page.