1,477 books banned across the U.S. mostly about race: PEN America

By Selen Ozturk

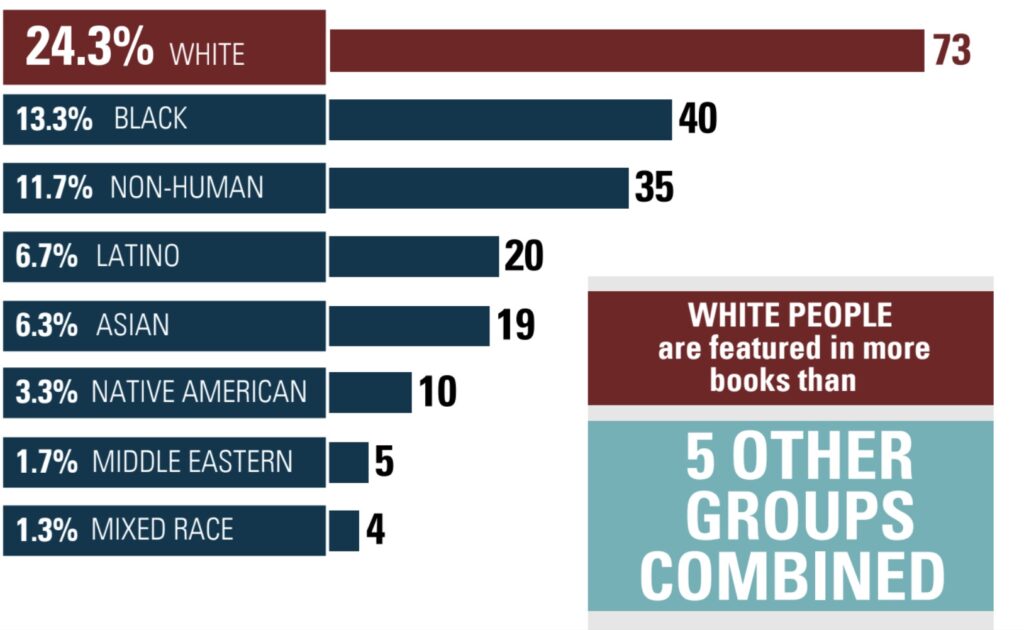

PEN America reports 1,477 individual U.S. book bans during the first half of the 2022-2023 school year — 28% more than the prior six months. Forty percent of books banned from July 2021 to June 2022 had protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color; 21% had titles indicating race issues.

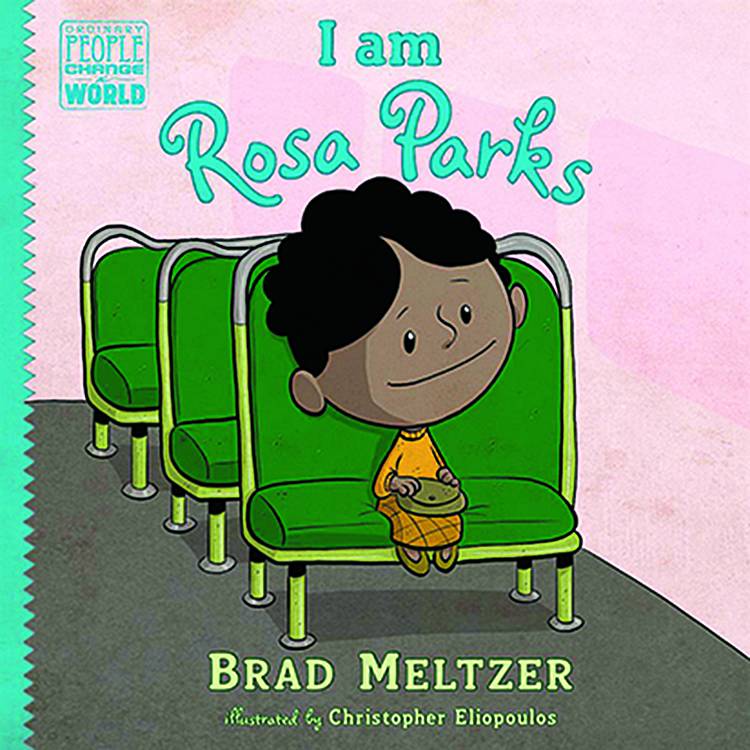

Examples of such banned books include “I Am Rosa Parks,” “I Am Martin Luther King, Jr.,” “The Bluest Eye” and “The Hill We Climb.”

Although greater representation is an uphill battle on the legislative front, some states like Illinois — which, in June 2023, became the first to pass a ban on book bans — and California, which passed a similar bill in September — are making historic progress.

“As we work toward more freedom in this nationwide,” said Dr. William Rodick, “We’ll be using our report as a basis to work closely with publishers, teachers and curriculum advocates to make guides for reviewing what kids are reading, understanding the limits of how people, groups, and topics are portrayed in these books, and deciding how to present these books for the fullest understanding of what’s being portrayed.”

Rodick co-wrote with Dr. Tanji Reed Marshall a study of racial representation in U.S. school books by The Education Trust. The study published on September 14 states: Among 300 U.S. grade school books — randomly chosen, evenly across grade levels, from publishers commonly used in English language arts curricula like Scholastic and Penguin Random House — nearly half of the people of color are portrayed negatively.

“An increase of Black characters in children’s books is great,” said Rodick, “but we want to push beyond the count — not just whether they’re portrayed, but how often they’re portrayed in negative ways.”

“We don’t want anyone to remove or censor any books on the basis of their representation, or deem them bad or good; many which are limited are of indispensable value,” he continued. “We want to recognize the value of these limited books by adding more perspectives to them, to engage students with them more deeply. If a book presents a topic in a very problematic way, it’s not about whether the reader should approach it, but how they can approach it best.”

One of the books examined, for instance, is the autobiography “Ruby Bridges Goes to School.” In it, Bridges frames racial segregation as a personal issue, whereby certain white people think they should not befriend Black people.

Per the study, a more complex view of an adjacent topic is presented in the picture book “Nasreen’s Secret School,” set in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. In the story, the eponymous girl’s parents disappear and the regime forbids her to attend school and leave the house without a male chaperone or burqa. In defiance, Nasreen’s grandmother enrolls her in a secret school, where the girl takes solace in an outlawed world of art and literature at the encouragement of her teacher.

That Ruby Bridges’ personal perspective conveys a more limited representation of educational segregation than Nasreen’s does not mean that it isn’t an invaluable way to learn about it, Rodick emphasized. It does mean, however, that readers would learn more about it if the book were taught with others which present segregation in its social, economic, or legal dimensions, beyond this personal limitation.

In short, representation doesn’t stop at a mirror.

“We engage students not only when they can see themselves come to life on the page, but when they can see others come to life on the page, when they can step into others’ worlds through their experiences,” said Rodick. “A whole understanding of the people who have these experiences, however, you can’t get that through a single story — by anyone.” — Ethnic Media Services