Macho dancing goes virtual in Joel Lamangan’s ‘Lockdown’

By Joel David

A recent Philippine film release will be easy to overlook because it appears exploitative and merely topical – starting with its title, Lockdown. It recently ended its extended streaming run but it has been slated for inclusion in this year’s FACINE International Film Festival in San Francisco (also with a streaming option). The festival itself has what may be the strongest competition lineup in any recent Philippine film event, reminiscent of the glory years of the long-diminished Metro Manila Film Festival.

At first glance, Lockdown may be regarded as part of the series of films initiated by Lino Brocka’s Macho Dancer (1988), where rentboys contend with the sordid realities of Third-World existence. The director’s previous film, in fact, claimed to be the first authentic sequel to Brocka’s biggest global hit, as indicated in its title, Son of Macho Dancer. Most entries in this series tended to be weighed down by their humanistic insistence on the dignity claimed against all odds by their central characters, as well as by the insularity of the sex workers’ situation. MD started by nodding toward the degeneracy induced by the presence of U.S. military bases but abandoned those concerns once the title character set out for the metropolitan center.

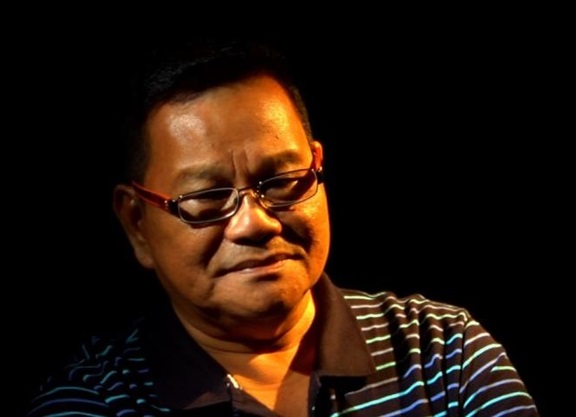

Joel C. Lamangan, who played the role of an unruly queer madam in MD, invests Lockdown with the same vision of an infernal underworld, but relocates the community to a coastal district, where Danny, an overseas worker forced to return after the global pandemic shut down the hotel where he worked, escapes from the mandatory 14-day quarantine to be able to raise funds for the recuperation of his recently handicapped father while acting as family breadwinner. The suburban setting considerably facilitates the mapping of territories that separate the seaside slum from the more affluent (and safeguarded) business centers, as well as the most militarized location of them all: the police compound with its discreet cluster of cottages intended for legally indefensible activities.

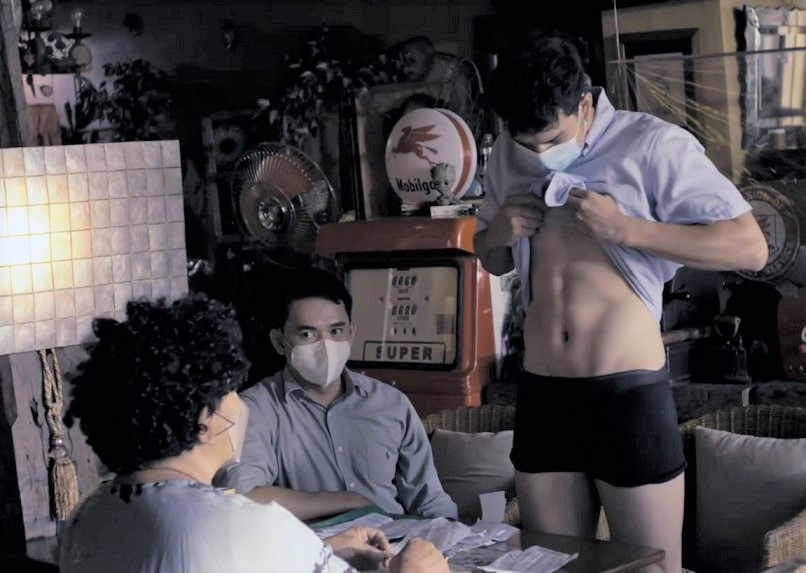

Like more aspirational working-class graduates than we realize, Danny worked out a gay-for-pay arrangement with Lito, a young entrepreneur, to be able to complete his studies; but since the pandemic was no respecter of overseas boundaries, Lito’s catering business also had to be suspended. The only income-earning activity the latter’s aware of is the one sustained by foreign customers, via live video exchanges, where native hunks offer to dance naked and engage in increasingly salacious displays, depending on the price the viewer pays.

The necessarily clandestine activity is conducted in Mama Rene’s Cafe, with the proprietor acting as barker, webmaster, trainer, and financier in charge of the performers’ income as well as a police official’s protection payment. Although initially nauseated by the abject nature of this version of sex work (as contrasted with the escort service he used to do), Danny manages to find some professional equanimity for himself in the tasks at hand, motivated by his father’s deteriorating condition and buoyed by the camaraderie of his fellow performers.

As it turns out, the further challenges that lie in store for the narrative hero escalate from this point onward, rapidly and terrifyingly. Lamangan ensures that we remain mindful of Danny’s plight by maintaining unconditional empathy with the character; his strategy is matched by a performance startling in its fierce commitment from Paolo Gumabao, one of the rare local cases where an offspring manages to surpass anything done by his actor-parent, Dennis Roldan.

Even with less-than-ideal material, Lamangan has always been capable of guaranteeing stellar performances, for himself and others. (For adequate proof, check out his other FACINE filmfest entry, One More Rainbow, where he draws out heart-tugging ensemble work from a trio of now-elderly stars from the Second Golden Age.) In Lockdown, he manages to differentiate a motley mix of video performers via sharp performative strokes: the final sob story, for example, is rendered by a cherubic actor who actually smiles throughout – a masterly touch that indicates how the speaker is aware that he uses the same lines to elicit sympathy (and, consequently, larger tips) from his customers, yet intends to inform his peers without adding to their already overwhelming burdens.

PC guardians will be thrown off by the resolutely negative queer imaging in Lockdown, where the higher the out-gay character’s position, the more malevolent he turns out to be. Yet this perturbing state of affairs should be seen as postqueer, rather than homophobic. These characters presume to stake their claims on limited resources and rewards, enabling impoverished local citizens to conduct transactions with better-heeled clients that they would never be able to encounter otherwise in their daily lives. More crucially, the global circuits of cash and power tracked via these personalities demonstrate the inroads made into the lives of our dispossessed by internet media – implicating in no uncertain terms the very same types of overseas viewers who would be ultimately watching presentations like Lockdown.

Joel David is a Professor of Cultural Studies at Inha University and was founding Director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute. He was given the Art Nurturing Prize at the 2016 FACINE International Film Festival in San Francisco and was this year’s recipient of the Writers Union of the Philippines’ Balagtas Award for Film Criticism. He has written several books on Philippine cinema, with his latest, a short manual titled “Writing Pinas Film Commentary,” available for free on his blog at https://amauteurish.com/books.