Study examines attitudes toward homosexuality in ‘70s Leftist movement

By Cristina DC Pastor

A new research showed how Filipino LGBT members of a U.S.-based Leftist organization in the 1970s navigated their emerging sexualities while maintaining revolutionary commitments.

Dr. Karen Buenavista Hanna discussed her article “Being Gay in the KDP: Politics in a Filipino American Revolutionary Organization (1973 to 1986)” in a talk organized by the CUNY Asian American/Asian Research Institute Forum on November 22. The study found that the KDP was “unique” compared to other groups in the Third World Left in that its LGBT members occupied leadership positions.

“In fact, it was the only Asian American organization in the 1970s that allowed gay or lesbian members,” it said.

Hanna, an assistant professor on Gender, Sexuality, and Intersectionality Studies at Connecticut College, has done extensive research on Asian American movements as a gender studies scholar. Before that, she was involved with organizing communities of immigrants, domestic workers, and young Filipinos in New York City from 2006 to 2011.

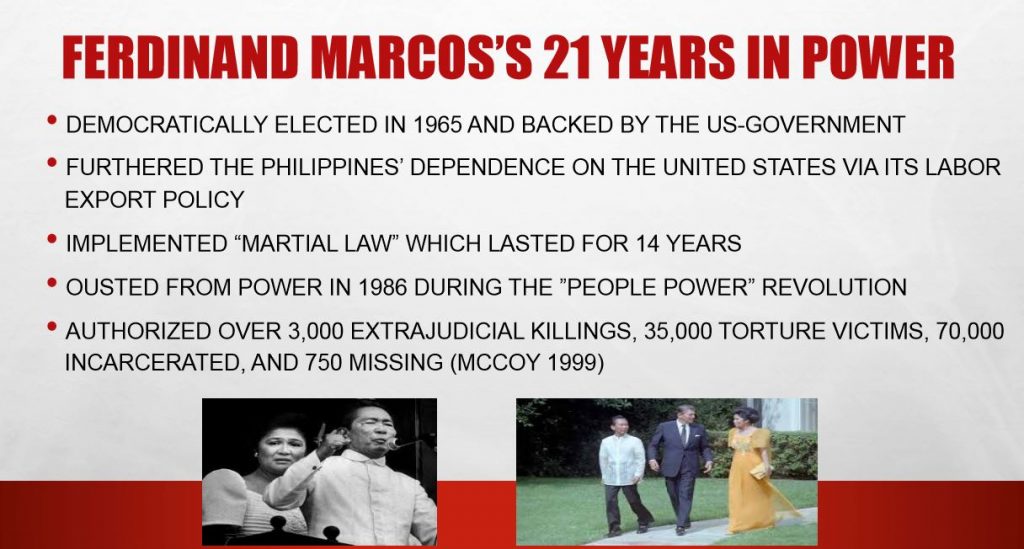

The KDP was founded in the San Francisco Bay Area as an anti-imperialist, anti-Marcos dictatorship organization a year after Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. In its heyday, the militant organization had chapters in nine U.S. cities, including Guam, New York, and Seattle.

One of the three founding members is identified as FilAm bisexual “Melanie Santos,” a pseudonym. She was imprisoned during martial law and deported back to the U.S. She co-founded the KDP in the Bay Area which became an important Filipino organization in the U.S. that denounced human rights abuses under the Marcos Dictatorship and lobbied against U.S. aid to the Philippines. The KDP tiptoed around Santos’s sexual orientation and would not openly discuss it worried it might be used to discredit its leadership.

The KDP had a cultural arm called Sining Bayan, and a newspaper, “Ang Katipunan.”

“It was quite sophisticated in its infrastructure,” said Hanna whose research interviewed almost 40 former KDP members. “It was local, transnational, and radical, and had two main goals. One, to fight for socialism in the U.S. and two, to support the revolutionary movement in the Philippines.”

An interview in Trinity Ordona’s 2000 study, “Coming Out Together” cited in Hanna’s research, describes how being a gay activist before KDP was founded in the early ‘70s tended to be “isolating.”

“It was a quiet thing. I could not tell anybody. Any inclinations, I had to can it. I had to dance with a guy and yet be attracted to a woman. ‘Looky-loo, but not speak.’ You could see, but not use your hands or mouth…”

Said Bruce Occena, a member of the KDP National Executive Board based in the Bay Area, who was interviewed in 2015. “Even though there was no explicit homophobia, there was still a pressure…well, coming out is never easy. When you’re in a very intense, demanding situation and you hold a position of leadership, this was always the joke…–Okay, you can come out, but you’re not going to have time to find a boyfriend or girlfriend. (laughs).”

There was a shift in the way that homosexuality was treated in the KDP over time, and this was shaped by historical forces, among them the emergence of a Gay Liberation Movement in the early ‘70s and the AIDS epidemic of the ‘80s. During this time, ‘coming out’ became easier as fellow activists became receptive to emotional support. Many KDP members, such Gil Mangaoang, Ia Rodriguez, Jaime Geaga, and John Silva got involved in AIDS advocacy as part of their political activism.

In its early years, one member left the organization over disenchantment with not being able to freely express his homosexuality. Those who stayed behind had to repress or “subsume their sexuality” at the risk of being viewed a security risk or not a true militant, mirroring the homophobia of McCarthyism and the revolutionary groups that inspired the KDP. In 1986, the KDP officially disbanded.

“While KDP was unique for its tolerance of gay and lesbian members, its starting point was imperfect, a reflection of the homophobic era that shaped it,” said Hanna. “Yet, it evolved. Understanding reasons for intra-movement homophobia in the 1970s can help to better understand the hetero-patriarchy that continues in current day organizing in the Filipina/o community and beyond. By recognizing the forces that shaped KDP’s evolution, we find hope that people and movements can and do change.”

© The FilAm 2019