‘Balangiga’ film: Amid the nightmare of war, a coming-of-age

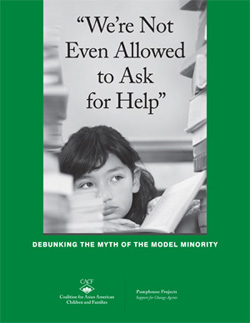

Kulas and Bola are the young boys who survive the village massacre in ‘Balangiga,’ a film set in 1901 at the beginning of the American occupation of the Philippines.

By Joel David

A small town (now a municipality) on the eastern part of Samar island in the Philippines, Balangiga [balan-HI-ga] was the site of the bloodiest conflict during the Philippine war of resistance against American colonization. In 1901, when Americans themselves believed that the war was nearing its end, Philippine revolutionaries succeeded in overpowering the 9th Infantry’s Company C soldiers stationed in the town, as a retaliation for its harsh measures intended to hasten the process of attrition. Less than 50 Americans were killed, but at that point it was considered the U.S.’s worst overseas defeat, and evoked memories of the then-25-year-old Battle of the Little Big Horn (more popularly known as Custer’s Last Stand), where over 270 American soldiers died.

Little Big Horn had massive and far-reaching consequences for Native American opposition to Manifest Destiny, which by then had transmuted into “Indian removal.” The U.S.’s overseas expansion was also premised on this mystical self-serving belief, with several veterans of the wars against Native Americans participating in the subjugation of the first formal European territory in the Orient, then known as Las Islas Filipinas (translated by the next colonizers as Philippine Islands). General Jacob H. Smith claimed to be one such veteran, but had actually only seen action in the Civil War. Deploying racist and apocalyptic language, he ordered his subordinates to “kill and burn … [all persons] capable of bearing arms” on the entire island of Samar (the third biggest in the Philippines, after Luzon and Mindanao). Smith earned for himself the nickname “Howling” by announcing his intention to turn the island into a “howling wilderness.”

The U.S. Army’s retaliation made American newspapers’ term for the account of the Philippine revolutionaries’ attack, the Balangiga massacre, ironic in contrast. A number of Filipino authors have called the retaliation the burning of Samar (with a 1974 movie, scripted by novelist Wilfrido Nolledo, titled “Sunugin ang Samar”). The entire occurrence makes it the precursor of subsequent American atrocities in Vietnam and the Middle East, but is lesser known than the later media-covered incidents or even the historical recounting of the “pacification” offensives directed at Native Americans. A recent release, titled “Balangiga: Howling Wilderness,” is premised on the retaliatory campaign, and made its own mark on local film history by winning best-film prizes in both the original academy as well as the original critics’ competitions. (Both groups have selected only four similar best-picture winners earlier, in over four decades of their rivalrous coexistence. The version of “Balangiga” that they awarded, and which I also viewed, was a work-in-progress prior to being further trimmed to significantly less than its two-hour running time.) The film is scheduled for theatrical release mid-August in the Philippines and will be screened at a few major (non-Euro) festivals, with U.S. screenings still in the planning stage.

“Balangiga” details the flight of an old man and his 10-year-old grandson, from whose perspective and consciousness the entire narrative unfolds. The boy’s name, Kulas, links him with another contemporaneous though older character from an earlier film, Eddie Romero’s “Ganito Kami Noon … Paano Kayo Ngayon?” (1976); both share the (pre-automotive) road-trip structure encompassing their lead characters’ coming-of-age. But whereas the earlier Kulas was also a dispossessed peasant traversing the turn-of-the-century Philippine countryside, good fortune smiles on him at several points in his journey and adequately prepares him for participating in the anticolonial resistance movement suggested by a benevolent and committed Chinese Filipino that he meets along the way. “Balangiga”’s Kulas, despite his and his grandfather’s flight from conflict, is an even more radical figure. The fact that the movie resolutely refuses to share the feel-good humanism of “Ganito Kami Noon” and strews the otherwise ravishing landscape with dead mammals (mostly human corpses) is only the starting point in articulating this difference.

What makes Kulas transgressive is the authenticity of his participation in the nightmare of war, whenever the opportunity presents or imposes itself. He saves a toddler, the only survival in a village massacre, and successfully attacks an American soldier-straggler, by way of avenging the murder of Melchora, his beloved water buffalo. Yet in defiance of the war’s horrific reality, he persists in having playful, though understandably surreal, dreams, and plays childhood games by himself and with Bola, the kid he saved and calls his brother. “Balangiga” is, in a sense, simply a commemoration of Kulas’s rites of passage – confronting death, rescuing Melchora and Bola from harm, learning to pacify a traumatized infant and cook food properly, ministering to the sick, and burying the dead, among other skills that Filipino children have since then been forced to learn on their own.

The film’s director, Khavn (whose credit is preceded by “This is not a film by”), has made over 50 feature films (in a list he titles “This Is Not a Filmography”) and over a hundred film shorts since the 1990s. Aside from already being the most prolific Filipino filmmaker at such a relatively youthful age, he also has the distinction of presenting the temporally longest Filipino film, the 13-hour “Simulacrum Tremendum,” classifiable as a poetic, creative, or hybrid documentary screened at the Rotterdam Film Festival in 2016, with the director accompanying the presentation, on the piano. Self-identifying as punk, Khavn collaborated on “Balangiga” with his partner, Achinette Villamor, as writer and producer, and the gifted queer author Jerry B. Gracio as co-scriptwriter. Villamor and Gracio are articulate, humorous, and (not surprisingly) transgressive social-media influencers, while Khavn prefers a more low-key presence. In one of his rare past interviews, he had extolled the system of independent production for how it had allowed him to be extraordinarily productive; some of his more recent work, “Pusong Wazak: Isa Na Namang Kwento ng Pag-ibig sa Pagitan ng Kriminal at Puta” (translated as Ruined Heart: Another Lovestory between a Criminal and a Whore, 2014) and “Ang Napakaigsing Buhay ng Alipato” (Alipato: The Very Brief Life of an Ember, 2016), possibly even more impressive a work than “Balangiga,” already evince a longing to speak to the Philippine mass audience.

Yet it is “Balangiga” that manages the feat, with little better than a shoestring budget enhanced by percipient performers and audacious cameos by other punk Pinoy celebrities. Khavn deploys cinematic tricks (stop-motion animation, disorienting lenses, startling drone footage, etc.) as well as basic special effects that serve to emblematize the childhood world of Kulas. His persistent (though inevitably sordid) humor, tenderhearted embrace of Otherness, and contempt for everything represented by modern existence and its enforcement via wholesale genocidal-if-necessary violence – these make of “Balangiga” all that Filipinos can claim so far as their retribution for the incredible injustice visited on the country’s distant central island over a century ago. Its triumph as a work of art keeps the memory alive, marks the emergence of the first people’s artist from the high-art Valhalla of European film festivals, and calls for further progressive people’s initiatives that the still-ravaged nation will have to find ways of summoning.

Joel David is Professor for Cultural Studies at Inha University in Incheon, Korea and was founding Director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute. His archival blog, Amauteurish! contains digital editions of his books and articles on Philippine cinema.

© The FilAm 2018