A visit with a Filipino detained by ICE

By Mariel PadillaIn the waiting room, a handful of people wait for the security guard to call their names. An elderly man with a black hat and wooden cane taps his foot. A young woman rocks a baby. Melanie Dulfo enters the detention center, walks past the seated people and tells the security guard behind the counter: “We’re here to visit Ronald.”

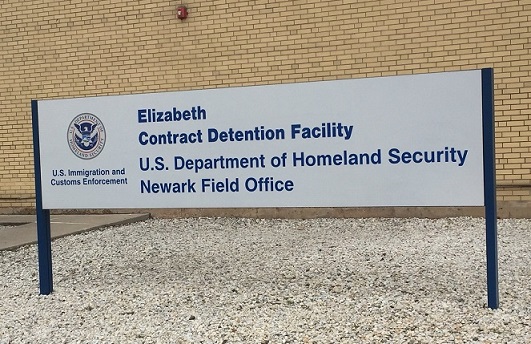

This is the second time Dulfo has visited the Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey in the past few months. She’s here as a member of FOCUS, a new coalition of Filipino organizations. Launched in January, FOCUS—Filipinos March for Community, Unity and Safety—regularly visits Filipinos held in ICE detention centers.

“People in the community don’t really know about the detainments,” says Laura Austria, a FOCUS organizer. “Or if they do, they don’t talk about it.”

Last year, ICE arrests in the country increased by 30 percent, according to Pew Research data. However, the number of non-criminal arrests jumped 146 percent under the Trump administration. Nearly half the immigrants being detained in New Jersey have no criminal history, making it the state with the largest percentage of non-criminal ICE detainees.

The security guard looks Dulfo up and down. Dulfo, who’s 33, is short, about five feet tall with a pixie cut that makes her look 10 years younger.

“I need to see I.D.,” the guard says.

Dulfo hands over her driver’s license. She stores her purse, phone and car keys in a locker. Then she’s buzzed into the next room, where she removes her shoes and walks through a metal detector. Laminated signs taped to the doors reminding visitors of what they can’t bring inside.

“This is kind of intense,” Dulfo says, glancing around.

When the opposite wall slides open, Dulfo steps into a small cafeteria with 13 square tables. It’s late morning and almost every table is occupied. Inmates are allowed to speak with visitors for one hour.

Not a choice

When Dulfo was 19, a college student in the Philippines, she vocally opposed the Philippines’s economic dependency on overseas workers. More than 10 percent of its GDP comes from remittances sent home by Filipinos working abroad.

“Migration is not a choice,” Dulfo says.

So when her parents moved to New York and told her she would have to come too, Dulfo resisted. She eventually agreed to apply for a U.S. visa when her mom warned she might never see her parents again.

In the U.S., Dulfo stayed involved in migrant workers’ rights. She is the northeast regional coordinator for the National Alliance for Filipino Concerns (NAFCON) and works at Apicha Community Health Center in Lower Manhattan as the director of community health education.

Dulfo sees the Filipino economic model of forced migration and the Trump administration’s push against immigration as connected issues, especially as ICE detains more and more non-criminal immigrants.

“There are detained people who don’t know what they’re signing and are at the point of giving up,” Dulfo says. “We want to show them there are community members with resources they can tap into. Show them they’re not alone, but part of a larger system.”

‘The Professor’

Dulfo takes an empty table facing a heavy metal door. After about 10 minutes, Ronald is escorted through the door. In his 50s, Ronald is a little over five feet tall and wearing a navy smock, the color indicating his minimum security status.

“Kuya Ronald,” Dulfo greets, standing up to give him a hug. Because Ronald’s case is still ongoing, his last name is omitted.

A detention facility in Elizabeth, New Jersey. At the time of the interview, there was only one undocumented Filipino immigrant behind bars.

Ronald, an electrician from the Philippines, came to the U.S. about 10 years ago. In January, he was arrested for trespassing on a construction site the he mistakenly thought was abandoned and detained due to his undocumented status. Ronald was looking for old construction equipment to sell with several other men, but he was the only one to get caught.

Twenty detainees live in each dorm. Ronald, the only Filipino at the Elizabeth Detention Center, shares his dorm with Russian, Slovakian, Polish and African men. They do everything together—eat, sleep and watch T.V., he says.

“The key to this place is patience. When people try to start anything with me, I try and keep my head down. I smile and say ‘bye bye’ because if you lose your temper or even touch someone, it’s ‘The Shoe’ for you,” Ronald explains. The Shoe, inmate slang, means solitary confinement. “So I try to keep to myself; I’m usually reading. They call me ‘The Professor.’”

“Oh shoot,” Dulfo interrupts. “I meant to bring you a James Patterson book. I completely forgot.”

“Whenever I finish a book, I just start it again from the beginning,” Ronald laughs.

“I’ll bring it next time,” Dulfo promises.

“It’s hard in here,” Ronald says. “Everyone is stressed and depressed. I often see guys just sitting and staring and counting the bars.”

An inmate sitting directly behind Ronald talks animatedly to a woman visitor while a blue-eyed, curly-haired child runs around the table. Every time the energetic child passes, he taps Ronald on the back and each time Ronald pauses to coo: “Why, hello there.”

Nearly a third of the tables have small children. Two little girls with big white bows in their hair ran to greet one inmate when he entered the room. Another inmate danced over to his infant son and spun him around in the air before sitting down.

Loud banging immediately silences the room. All heads turn to look at the metal door, where a large male security guard pounds on the door from the other side, trying to get a female guard’s attention. The female security guard in the cafeteria looks at the door, then at the visitors and starts laughing.

“Don’t worry everyone, it’s not the police or anything,” she jokes. “Look at your faces. It’s not the cops.”

No one else laughs.

Something wrong

As she pulls out of the Elizabeth Detention Center parking lot, Dulfo calls her husband to let him know she’ll be back in Queens in an hour and a half.

With both hands on the wheel, Dulfo’s eyes flit back and forth from the road to her phone’s map. She talks about her childhood, her exposure to people in the slums and her anger at the economic migration model.

“When I spoke to farmers in the Philippines, they described a system where they had to buy everything from their landlord and then they had to give most of their harvest to the landlord,” Dulfo recalls.

Since moving here, Dulfo has worked with many immigrant communities.

“This isn’t people being lazy. There’s something wrong with us and the system.”

Mariel Padilla is an investigative fellow at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, where she recently graduated with a concentration in data. Prior to that, she covered breaking news for The Cincinnati Enquirer and contributed to the 2018 Pulitzer-prize winning project, “Seven Days of Heroin.”

© The FilAm 2018