The day I found a carabao’s tail

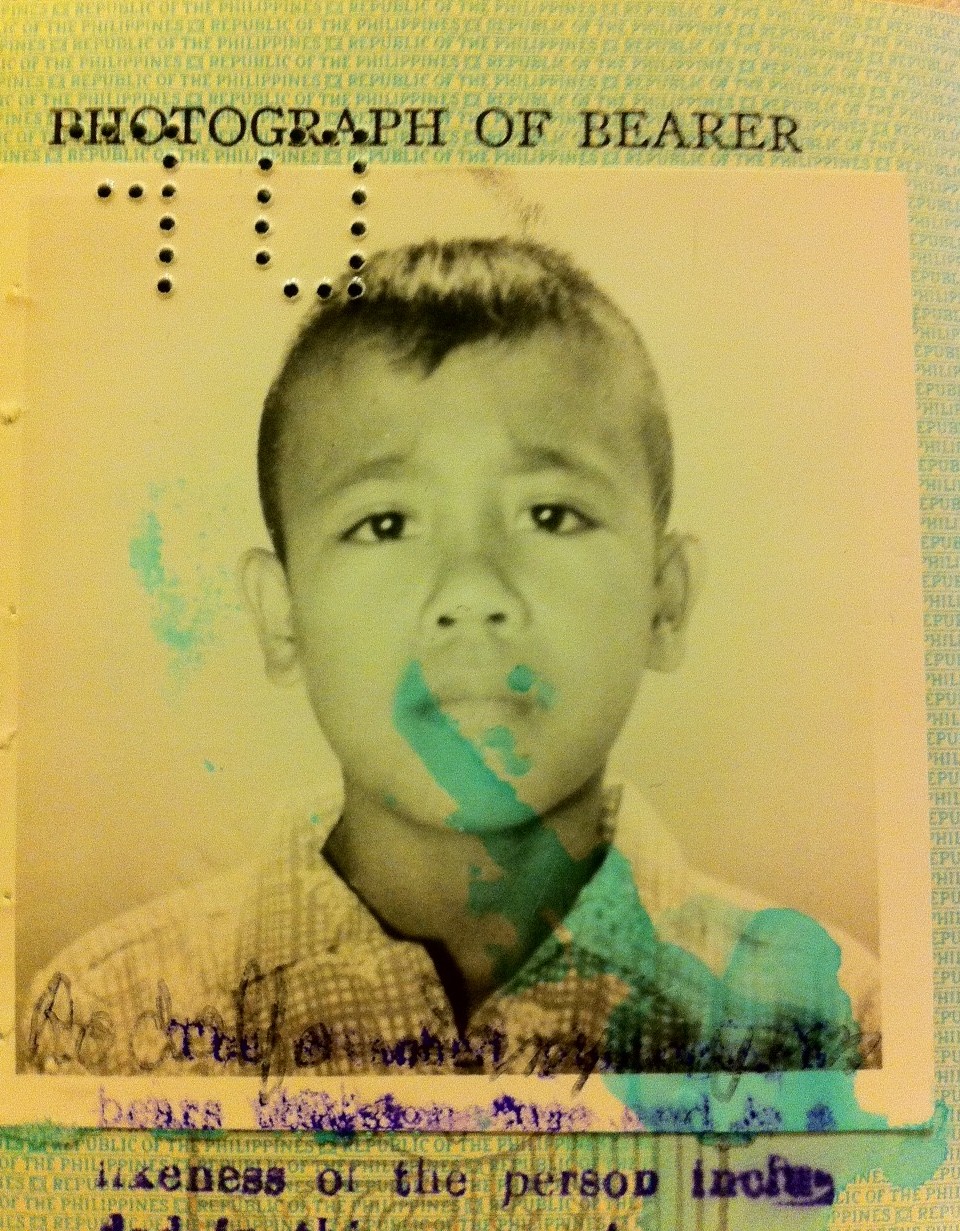

By R Sonny Sampayan-Sampayan, USAF Ret.

There is one memory that always brings me home to Barrio Santo Nino in Binalonan, Pangasinan. I was born into poverty with a family of seven children of which I was the third. Life was hard and food was hard to come by so we all worked together to bring home food to nourish the family.

When my uncle Valeriano Sampayan visited us from Hawaii in the early 1960s, he purchased an electric-powered hollow block machine for my father to help him earn a better living for his family. My father kept the hollow block machine in the Tagamusing River where he spent six days a week to meet the demands for hollow blocks.

One day, the rainy season came, and it rained for three days in a row. My father would always stay alone in the river to watch over his hollow block machine. When evening came on the third day of rain, the strong gush of water from the north overflowed the river. My father was able to escape the flood with only the shirt on his back. The rain continued and flooded our entire village. When the flood water subsided, my father went back to the river only to find that his hollow block machine was swept away by the great flood. With my father’s thriving business gone, the only thing that we had left was the roof over our heads.

To help my father, he asked my two older brothers and I to sell ‘pandesal,’ the breakfast bread in the Philippines. He also asked his friend to allow us to sell Bannawag, the famous Ilocano magazine.

Every day at 3 in the morning, we would wake up and go to the town proper in Binalonan. I would walk barefoot for nearly two miles to the bakery to pick up our allotted ‘pandesal’ to sell. During the hours of darkness, the three of us would walk together as we started our route. I always carried pebbles in my pockets to chase away the dogs that were always barking at us. I also carried a stick to chase the away the dogs if I ran out of pebbles to throw at them. To make sure that customers could hear us coming, we would yell at the top of our lungs, ‘Pandesal! pandesal! pandesal!’

Every day at 3 in the morning, we would wake up and go to the town proper in Binalonan. I would walk barefoot for nearly two miles to the bakery to pick up our allotted ‘pandesal’ to sell. During the hours of darkness, the three of us would walk together as we started our route. I always carried pebbles in my pockets to chase away the dogs that were always barking at us. I also carried a stick to chase the away the dogs if I ran out of pebbles to throw at them. To make sure that customers could hear us coming, we would yell at the top of our lungs, ‘Pandesal! pandesal! pandesal!’

By the time we reached the end of our route, we still had plenty of bread left in our containers. We would go see my father in our house and ask him to buy all the ‘pandesal’ that we had left over but he didn’t have any money to buy them. When we got hungry, we would reach into our containers and eat a few. As it turned out, we were eating our profits. We tried selling ‘pandesal’ for a few weeks and we also tried selling the Bannawag, but neither business venture was profitable.

By the time we reached the end of our route, we still had plenty of bread left in our containers. We would go see my father in our house and ask him to buy all the ‘pandesal’ that we had left over but he didn’t have any money to buy them. When we got hungry, we would reach into our containers and eat a few. As it turned out, we were eating our profits. We tried selling ‘pandesal’ for a few weeks and we also tried selling the Bannawag, but neither business venture was profitable.

It was a hot day in April 1966, and we had eaten the last pot of rice we had with dried fish or ‘tuyo.’ Later in afternoon, I woke up from my nap and decided to wander into the field in search for our next meal, hoping to find food for dinner before the sun faded.

I went to look for ‘malunggay,’ ‘saluyot’ or anything that resembled green leafy edible vegetables. I walked barefoot on the earth that was now cracked by the simmering heat of summer. As I walked the field, I came across a scraggly dog, tugging in its mouth an 18-inch tail of a butchered carabao. I recalled that there was a wedding on this day and I assumed that the dog just came from the reception and escaped with the prize of the day. I recalled the excitement of possibly succeeding to bring in my family’s next meal — if I could only distract the dog and force it to abandon the carabao’s tail.

I picked up several stones and waited with a thudding heart. When the dog was within throwing distance, I threw the stones to distract and force the dog to abandon the tail. I didn’t hit the dog directly, but I put enough fear to make the dog abandon the carabao’s tail. I raced to retrieve the tail and discovered that the meat was still fresh. I ran home quickly and excitedly called out, ‘Nanay, nanay, tatay, tatay’ as I approached our nipa home.

My parents were amazed at what I had brought home. My home came alive with preparations for the best meal we’ve had in months. It felt like we were cooking for a fiesta. Along with the carabao’s tail, we cooked the ‘saluyot,’ ‘ampalaya’, and other vegetables we had gathered earlier in the day.

I would never forget our particular dinner on that hot April day when I was 6 years old. Although it has been more than 45 years since I found the carabao’s tail, I know that to this day, there are children in my village of Binalonan, Pangasinan that live in poverty, and are still selling ‘pandesal’ and Bannawag. I also know that there are children in my village that are still looking for their own carabao’s tail.

R Sonny Sampayan-Sampayan is an executive assistant for a major European bank in Manhattan. He is a University of Phoenix student majoring in Public Administration, and expected to graduate in August 2011.

It’s a sad commentary indeed that a lot of our people are to this day still looking for their piece of the carabao’s tail. This is a challenge facing us as a people and must be the top priority of our leaders.

Every once in a while, a beautiful personal essay comes along reflecting on what we have become because of where we come from.

Cristina

Sonny:-)

Great & touching story. Should be included in a children’s book.

Hi Sonny:

It is a very interesting essay.

I also pity the dog for losing his meal.

I just hope that dog had short memory.

Good to hear your childhood struggles that should inspire others.

Keep writing.

Take care.

Joseph

JOSEPH G. LARIOSA

Correspondent

Journal Group Link International

P. O. BOX 805072

CHICAGO IL 60680-4112 U.S.A.

Real hunger is something that most Americans have never known … and I do not want the experience.

For Vietnam USAF escape & evasion training, they gave us only beef broth (to keep up our body salt levels for health) for 24 hours of strenuous evasion, then a simulated “prison camp” where we were given raw rice and several cans of sardines for about 50 men (I was the cook, and did a good job of cooking the rice in old metal trash cans), then dumped us in the mountains of Washington State with a compass, some raw onions, and a live rabbit for 10 men. We killed & ate the rabbit and boiled the onions, picked wild blueberries along the trail, camped, then walked through forest and underbrush to a “pickup point”. This part of training was partly to teach us what real hunger was. A truck then took us to a McDonalds restaurant where I had a hamburger and milkshake which I promptly threw up because it was too rich for my starved stomach.

I thought that was real hunger, then I read Sonny’s story of long-term hunger as a child, and he went through hunger so much more than mine, that I can only barely imagine what it must have been like for him. It reminds us of the millions of people in the world who go hungry every day.

Sonny,

This is a great personal story. Very funny, touching and compelling. I can relate to it in many ways as I grew up in a farm myself.

I trust you are writing a book because these are rich stories you are sharing.

Your posts about Filipinos in the US are very informative and entertaining. Keep up the good work.

Thumbs up and Thanks.

Thank you, Sonny, for sharing your story. I am delighted to see that you are writing (and writing soooooo well). Congratulations. Also, I love it that you have kept in your awareness the children in the Philippines who are still searching for food to bring home to the family. Sometimes I think the only way we human beings really understand compassion is through suffering ourselves and overcoming the obstacles. And lots of times I wish there were easier ways to learn our humanity. Part of my love for my sister is that, when we were children (and I was really just an infant) my sister would forgo eating dinner (now and then) so that “the baby” (me) would have some thing to eat. I’m sure you know the bond that they act of love created between us. Of course, as an infant I didn’t understand, but later in life it hit me and I wondered at her generosity.

I just saw something on 60 Minutes last Sunday that showed bus pickups for public school students who are homeless or living in temporary 1-room places wtih their families, many of whom lost their homes during the Great Recession. They interviewed the children and asked them what it felt like to be hungry, and one child said it was like a big black hole; another said his hunger kept waking him up all through the night, so he was both hungry and sleepy in school during the day.

I know poverty in America is not what it is in the Philippines, but, in a way, it is more horrible to me because we are the richest country in the world, and yet the commentator said it is projected that one out of four children will be living in what America considers “poverty” (less than $25,000/year for a family of four, I believe) in a year or two. In that same 60 Minute story, it showed neighbors who took in families who lost their homes. It showed other acts of generosity and kindness. And it is always those acts of kindness that make me cry because they break through the walls we protect ourselves with. There is no defense against a generous spirit, and your own joy at the prospect of bringing the oxtail home, tells me, once again, what a wonderful spirit you have.

What a heartwarming essay.

[…] He wanted to become an aviatorThe son of World War II veterans advocate R Sonny Sampayan of New York was killed in a vehicular incident October 2 in Riverside, […]