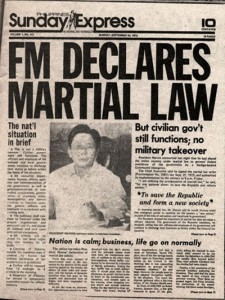

After 42 years, exhuming a bitter memory of Martial Law

By Julia Carreon-LagocOn September 21, 1972, a day of infamy in Philippine history, Ferdinand Marcos proclaimed Martial Law. This year on the 42nd anniversary of its proclamation, I exhumed this bitter remembrance — the memories ever fresh as when they were first written.

NEVER AGAIN! In bold capitals and with an exclamation point. That’s the comment I wrote in the visitors’ book at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Never more was man’s inhumanity to man so starkly documented. The evil, the depravity, the mercilessness of it all boggle the mind. Humankind must not experience another Hitler. NEVER AGAIN! That I will write again, as I am writing it here.

In equal revulsion, I say NEVER AGAIN! should Filipinos be subjected to another martial rule. The horrors of the Marcos years stay intact in the mind. The pain and sacrifice, tears and blood of the victims of Martial Law are “too deep for tears,” to use a line from poetry. Hard though it be, we tried to invoke forgiveness, to soften the heart, and even to cast off resentment for those who figured in one dark episode of our life. Nevertheless, forget we won’t, because forgetting is to lose the courage to confront, challenge, resist, and defy the imposition of another Martial Law. That is what we have to do, what we must do if life is to be worth it. Stand up for Liberty or existence be damned!

As I’ve written in a previous column, there are memories that strengthen, and this remembrance is mine to share: September 25, 1972, a Monday, and a working day. My husband Rudy, a labor attorney, was typing a decision on a labor dispute in his office when he was “invited” to Iloilo City’s Fort San Pedro. For a “few” questions, the military said. The invitation lasted for six months of detention in the stockade and two months of provincial arrest.

Detained without charges. Why? These questions I used to ask myself: Because of standing counsel to student demonstrators who pitted guts against the Marcos dictatorship? Because he was too loud, in both print and radio, espousing the sovereignty of our nation? Because he spoke in forums that sought to elevate the masses through education? All these are within the ambit of the freedom of expression. But, of course, not he or anybody at all could reason out with the functionaries of the dictator.

For six months, it was a daily routine to bring in food and fresh laundry to the stockade in Fort San Pedro. On off-school days, I came with the four kids in tow – Rose, Roderick, Randy, and Raileen, aged 12, 11, 9, and 7. They would ask why this fate of a stockade for their father, he “who couldn’t even hurt a fly.” Why? I would mention love of country and people, in the hope the kids would understand. I told myself, “Later the children will all grow up and some such abstract things as steadfastness to ideals they will understand and, understanding, they will imbibe the truly good and right.”

The days were long; they seemed interminable. I drew strength from the young detainees’ own indomitable will to overcome the uncertainties of the future. During those trying times, there were people who avoided our company, putting on the blinders when we crossed paths. However, we didn’t lack for kind friends and relatives who extended moral as well as financial support. To them, I am forever grateful.

Rudy’s parents were Manila residents, so were the families of her three sisters, Nelly, Asuncion, and Linda. His detention in the Marcos stockade was kept secret by his sisters from his aged parents, Aurora Gedang and Leoncio Lagoc, now both departed.

When Mama, Rudy’s mom, got very sick, Papa told Rudy’s sisters, “What kind of a son is that (Rudy is the youngest and only son) who cannot even visit an ailing mother?” But how could he? Being on provincial arrest, he was not allowed to go out of Iloilo. Mama was dying, and so we pleaded to the powers-that-be to let him go visit his mother in Manila. Permission was granted on the condition that he had to be accompanied by a PC escort. Sgt. Dangan (I can’t recall his first name) was assigned to escort him. We had to scrounge for the plane fare of the PC escort as well.

As the story goes with some folks who wait for the arrival of a loved one before their spirit would leave the mortal flesh, Rudy was beside her deathbed when Mama breathed her last.

Atty. Rudy Lagoc retired as head of the National Labor Relations Commission, Region VI, and continued legal work with the Iloilo Legal Assistance Center, a human rights group, until his death in 2012. Mrs. Lagoc was editor of the Aqua Farm News and Aqua Dep’t News, newsletters of the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. Their daughter Rose, a scholar at the Asian Institute of Management, is a financial advisor at Green Retirement Plans. Roderick is a Department of Labor officer. Randy is a physician internist in the Hilton Head Regional Medical Center in South Carolina. Raileen, the youngest, is a pediatrician in Redding, California. Send comments to the author at jclagoc@gmail.com.

Dear Julie,

It’s not only yours and Rudy’s martial law days which are being exhumed. Ours too. Thank you for being so vivid in putting into words the bitterness created by injustice but also the joy of family support for a cause which bolstered his morale. Rudy was lucky to have such a family.

Rose A