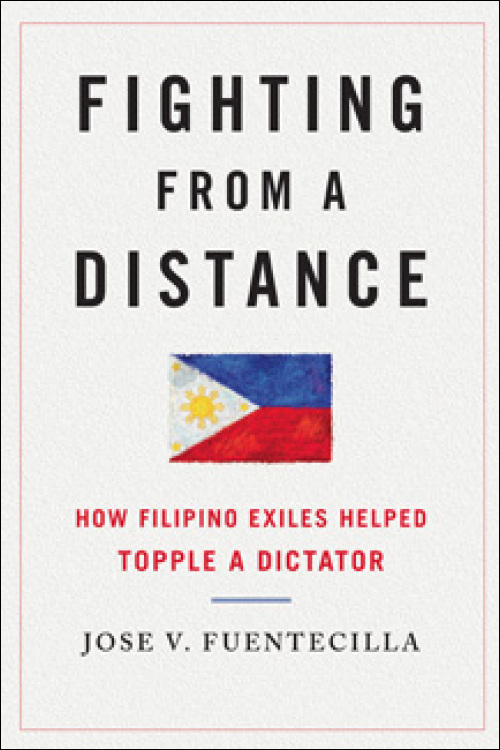

Manglapus, Gillego and the struggles from exile of a N.Y.-born anti-Marcos movement

Fighting from a Distance: How Filipino Exiles Helped Topple a Dictator

By Jose V. Fuentecilla

University of Illinois Press

2013

By Cristina DC Pastor

It is a book that triggers memories – some good and some not so bracing.

That is how the book “Fighting from a Distance: How Filipino Exiles helped Topple a Dictator” by Jose V. Fuentecilla struck me as I read the 162-page softcover published by the University of Illinois Press.

They were then pejoratively called “steak commandos” by minions of Ferdinand Marcos, dismissed by the dictator for living it up in the plush comfort of the United States. The book writes of Manglapus, as a “hunted” man, subleasing a meager apartment from a Filipino couple in New York City and “learning to steam rice and cook… nilaga and sinigang.”

The book narrated how the Movement for a Free Philippines (MFP), led by Raul Manglapus and Bonifacio Gillego, were hounded by the FBI at the instigation of the U.S. government – chummy friends of the Marcoses — who seized sole power in 1972 and jailed his critics.

This struggle by exiles who were shunned by large parts of the Filipino community and harassed by a Republican government, led by Marcos pal Ronald Reagan, speaks to the power of persistence in fighting a cause.

As one who intimately witnessed the birth of the MFP, Fuentecilla writes of how this grassroots organization inspired the overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship which destroyed the democratic framework of the Philippines, and what the MFP endured in the hands of the pro-Marcos White House.

A month after Manglapus was joined by his family in the U.S., followed by retired Army intelligence officer Bonifacio Gillego, lawyer Charito Planas, dean Gaston Ortigas, and others, MFP was organized in Manhattan in September 1973. It was a full year after martial law was proclaimed by Marcos in 1972.

The stressful life of an exile claimed the young life of Raoul Beloso, who committed suicide by hanging himself in his Broadway apartment. He was then a ranking official of the Department of Agriculture who fired off an angry anti-Marcos opinion piece for The New York Times. He felt homesick, missed his wife and was broke, the book alleges.

The Filipino community greeted the movement with “apathy and fear” especially among newer immigrants, says Fuentecilla.

“Their first order of business was to get settled – employment, housing, education for their children – there was no room to indulge in politics,” he writes.

Eventually, known activists and supporters of MFP were blacklisted. The environment then was rife with reports of a plot to assassinate Manglapus. There would splits within the ranks, and break-away groups being formed denouncing the MFP as too “moderate” or “centrist.” Through it all, the movement grew and chapters were formed across the United States. Leaders turned to lobbying members of Congress, especially those investigating human rights abuses in countries that benefitted from American foreign assistance.

“How they persevered provides a lesson in organizing and sustaining efforts to overthrow a well-entrenched enemy,” says the author, an MFP stalwart.

While the main fight was spearheaded by Manila-based activists, the opponents of Marcos in the U.S. were no less ardent in their feelings for the country, he says. He acknowledges that these U.S.-based activists were “small in numbers and splintered in their solidarity” but their narrative has hardly been told until now. The reason for this book being published 27 years after the EDSA revolution that sealed the fall of the dictatorship.

The book explains to a huge degree how the coddling by the U.S. of Marcos stoked the anger of Filipinos and how this led to the eventual closure of U.S. military bases in the country, the biggest outside North America. It pounded home to readers how the U.S. harangues about democracy and freedom took a poor second or even third place to its abiding desire to keep its military bases at Clark in Pampanga province and Subic Bay in Olongapo.

Fuentecilla puts it well when he says, “The United States lost its Philippine bases, and a generation of Filipinos who lived through the agony of the martial law regime are deeply aware that the U.S. government sided with a dictator.”

When Cory Aquino became president, Manglapus came home to become a senator and later joined her government as foreign secretary. Gillego became a congressman who led the campaign for land reform.

Hello, I would like to know how I can get in touch with Mr. Fuentecilla. I am the niece of Raoul Beloso. My sister and I arrived a day after his death in New York. I would appreciate it if you could connect me to Mr. Fuentecilla.

Thank you.