The Marcos Dictatorship and the irreparable damage to a family and the Filipino experience

The Quimpo siblings: From overachievers to wanted figures, hunted down and tortured by the military. Photos: ‘Subversive Lives’

By Joel David

In the process of finalizing the current issue of Kritika Kultura, Ateneo’s online journal, on Ishmael Bernal’s “Manila by Night,” I went over some of the notes I took during the too-few interviews I had with the director. One of the statements he made, that our stories as a people are better told as a collective, became the basis of several articles and an entire dissertation on the film and its author. The format, which we can call by its description “multiple-character,” is a tricky one to pull off. Seemingly “social” fictions like “Gone with the Wind” or, closer to home, “Noli Me Tangere” typically begin with a large group of characters, then reduce the narrative threads until they focus on a hero, sometimes with a romantic interest or against an antihero, or (in the case of GWTW) a love triangle – which, by presenting a character torn between two options, invites singular identification and thus maintains the heroic arrangement.

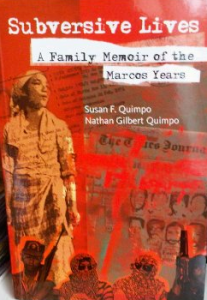

The multi-character film format actually originated in literature, so it would not be surprising to find it deployed more readily in fiction and theater, where the “star” demands of cinema can be more easily ignored. The more ambitious samples, like “Manila by Night” (and Bernal’s avowed model, Nashville), succeed in portraying, via the interaction of its characters, an abstract, singular, social character that embodies the conflicts, frustrations, and aspirations of the milieu the text’s figures represent. The unexpected delight of my current Pinoy reading experience, in this wise, was in recognizing several of these qualities (and then some) in a recent book, titled “Subversive Lives: A Family Memoir of the Marcos Years.” Listing Susan F. Quimpo and Nathan Gilbert Quimpo as authors, the Anvil publication actually comprises contributions from the Quimpo siblings and the widow of their brother (and I beg their understanding for not listing all of them in this review).

The Quimpos achieved fame (or notoriety, depending on one’s perspective) for having had several of them participate in the anti-dictatorship movement during the martial-law regime of Ferdinand Marcos. Since the only genuine opposition during most of this period was provided by the outlawed Communist underground, the Quimpo family, by its association, underwent dramatic upheavals, acute heartbreak, and occasional but still-too-rare moments of grace that would appear almost fantastic had the book been announced as a fiction. The fact that these events actually happened, related by the individuals who directly experienced them, provides the reader with a sense of how irreparably damaging authoritarianism has always been for our particular national experience.

I remember how, as a student at the state university, I could always rely on the fact that my smartest classmates would be sympathetic, if not involved outright, with student-activist causes – in sharp contrast with the situation I later observed as a teacher. “Subversive Lives” provides a panoramic chronicle of how the militarized dictatorship, profitable only to foreign and mercenary local business and religious interests, upheld the worst legacies of colonial education and magic-patriarchal morality: backward thugs armed, fed, and protected by the machinery of an irredeemably corrupted state were allowed to wield life-or-death mastery over the very people in whom, by virtue of their capacity to exercise discernment, creativity, and determination, the future of the nation would have resided.

The Quimpo children, in this respect, may be regarded as representative of the country’s best and brightest, had they emerged in another place, another time. Starting out as stereotypical overachievers, the only source of pride of their financially distressed parents, they grew up just when the storm clouds of tyranny were gathering; having moved to a cramped apartment near the presidential palace, they were initially witnesses, then active participants, in the increasingly violent protest actions then taking place in their neighborhood.

One of the most powerful dramatic undercurrents in the book is how the Quimpos’ parents coped with the spectacle of several of their children giving up their scholarships, then their bright futures, by moving from school dropouts to wanted figures, hunted down and tortured by the military. One of the sons recollects his reconciliation with his father at the latter’s deathbed, and his story suddenly breaks free of the storytelling mode, addressing his father in the present as if he were still alive, and as if no reader would wonder: “Talk to me. I’m your son…. Why don’t you express all your heartaches, disappointments, and frustrations?”

The siblings never shake free the realization that the paths they chose were not what their parents had hoped for them. If their parents lived long enough, they would have seen that the Quimpo children had been able to attain impressive career trajectories, covering several continents and participating in impactful projects (of which the book serves as group memoir) that would have been the envy of the more privileged families with their utterly predictable and vision-impoverished choices.

Even the sister who had opted for life as an Opus Dei numerary found inevitable parallels between her Order and the fascist system that her siblings were struggling against. The story of the retrieval of their brother’s body is hers to tell, and one would probably wind up smiling, in the face of the long-anticipated tragedy, at how she had managed to muster enough reserves of strength to confront and intimidate the military officers who felt like aggravating her and her grieving female companions, just for the heck of it. When, famished after the confrontation, one of them mistakenly brings one too many orders of Coke and the driver of their vehicle innocently asks who the spare bottle is for, then they turn toward their brother’s body and cry all over again, I could not help turning as well toward the best moments in Pinoy cinema, where our film-authors are so casually able to incite these tender combinations of humor and warmth amid overwhelming sadness.

The book ends with a controversy that has shaken up, and continues to do so, the Philippine revolutionary movement. The Quimpos who were then still involved were major participants, and express the opinion that the leadership they challenged had taken on qualities of the dictatorship that they had fought against and (in a sense) succeeded in ousting. Like the best Filipino multi-character texts, “Manila by Night” foremost among them, “Subversive Lives” is sprawling, occasionally meandering, sometimes indulgent, and necessarily open-ended. It is also gripping, heartfelt, insightful, and forward-looking, so much so that the aforementioned “flaws” would be a small price to pay for its still-rare literary largesse, just as the Quimpo children’s rebellion has made the country’s journey to a more meaningful present a trip for which we as their witnesses ought to be grateful.

Joel David is associate professor for Cultural Studies at Inha University in Incheon, Korea. He is the author of a number of books on Philippine cinema and was founding director of the University of the Philippines Film Institute.

The only proof about there story was the tales (book, movie, talk show money) that these events actually happened, to the individuals who supposedly experienced them, I met the President, and do not think he would ever have condoned these events, had he known. That is not to say that these things, if they actually happened, could not have been the work of General Ver and his lady friend, Imelda. Much of what they did has incorrectly been blamed on President Marcos. Too many people have made up fairy tales, just to be famous.

I met FM a few times too and worked several years for his media center. Our unofficial instruction was, in a worst-case situation, to make sure that no one criticized the president, even if everyone else (including Imelda) got blamed. So it’s just as easy to say that Marcos was directly responsible for a lot of the difficulties the nation went through but he managed to keep his image cleaner than everyone else’s. Remember, he not only controlled media, he also issued a decree punishing “rumor-mongering.” If we accept your (unproven) statement that “too many people have made up fairy tales,” then guess what – he could easily have made up his own before anyone else could.