Remembering Maita Gomez’s political activism, cool humor and cooking

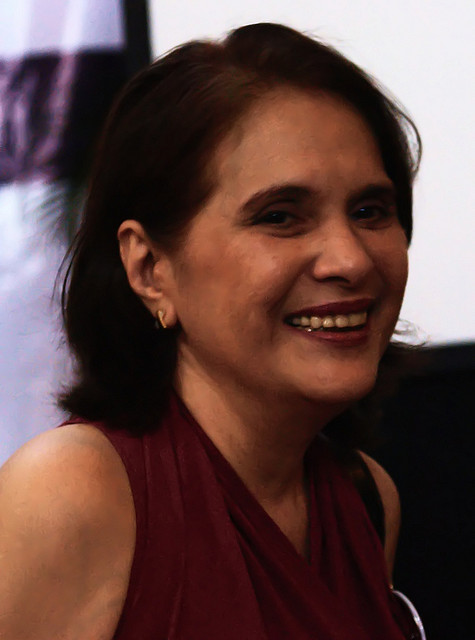

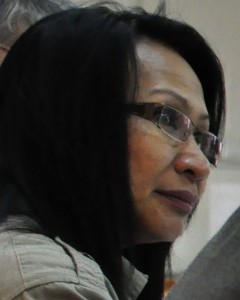

By Cristina DC Pastor“I screamed, I cried,” New York resident Indai Sajor recalled. She was inconsolable for days on hearing her good friend, women’s rights activist Maita Gomez, died July 12 in her sleep.

Indai, a gender advisor for the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, met Maita in the 1980s. Theirs was a friendship that would span four decades, a women’s movement that took root and flourished when they were both part of it, relationships and children.

“We were very close,” Indai told The FilAm her voice still faintly nasal, the sound of one who had been through many days of crying. “Our children grew up together.”

She was with the former beauty queen in January when she went home to the Philippines after the holidays. “Maita and I could be together and talk the whole day without getting bored,” she recalled. “Every time I go home she’d be the first one to know and then she’d make plans (for us) on what to do.”

She remembered how in some of their happily entwined chats they talked about getting old and not being too angry anymore. “Ibang issues pinapalampas na namin kasi tumatanda na kami, and we would both laugh.” Maita died of a heart attack in her sleep; she was 64.

Indai and Maita founded Gabriela — together with fellow activists Nelia Sancho, Judy Taguiwalo and Lidy Nacpil — possibly the first organized grassroots movement for Filipino women. It was founded in 1984 following a massive rally against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, and named after the legendary widow Gabriela Silang who fought the Philippines’ Spanish colonizers in the 18th century. Gabriela is now a partylist bloc with a representative in the Philippine Congress and has chapters in the U.S.When they met in the underground movement, Indai said she was not at all skeptical that Maita may be this bored, dilettante socialite who was dabbling in a cause just to get busy.

“She came across as very strong, very genuine, with no agenda at all,” she said. Over the years that they moved from province to province to further the revolutionary struggle, she found Maita to be a person of “integrity, dignity, one who stood her ground, very principled.” She was a “great strategist,” said Indai, and attributed this in part to Maita’s academic credentials, master’s degree in economics from UP.

True, Maita was born to an affluent family with a home in San Lorenzo Village and an hacienda in Pangasinan, but she was also “seeking challenges to reform society,” said Indai. “She could see how hard it was for the poor. It was a period of the Marcos dictatorship and she couldn’t just sit and watch the whole thing (injustice, killings, etc.) happen without doing anything.”

Around the time of her death, Maita’s activism had remained largely directed at mining and what she believed was the industry’s potential for human rights abuses.“She was working on the mining campaign, organizing coal miners included those in Asian countries,” said Indai. “Towards the end, she’s still trying to change things.”

But a sense of physical inertia was slowly creeping in. “She left an NGO she was with, she’d say magre-retire na ako. She wanted more time for herself,” Indai rewound some of their conversations.

Maita bought an island in Caliraya in Laguna where she was looking to retire so she could devote her time to writing. In April, Indai spent two nights there. “She loved to cook. We had shrimps with coconut and corn soup. I encouraged her to grow orchids. Those were fond memories.”

The two friends and others were contemplating authoring a book on the history of the women’s movement in the Philippines, and Maita was thinking of slowing down a bit.

“It’s one of our projects,” said Indai. “We wanted to reconstruct the development of the women’s movement in the Philippines. It’s a book that had to be written, and nobody would have the insights that we had. I’m still devastated that Maita died (before the book was written).”

Was she also writing her memoir before she met her end? Indai laughed. “She doesn’t believe in those things, hindi niya type. She will never write her memoir.”

More than her activist fervor, Indai will miss Maita’s sense of humor. She remembered a trip to a wet market in Manila to get some fresh shrimps and Maita haggling with a vendor. “She would tell the palengke guy na pabiro: Ang mahal naman, sige dagdagan mo na lang ng isang hipon, and she would still pay. She was really funny,” said Indai. “Cool to be with.”

The death of Maita is still a shock to Indai. “She wasn’t sick at all, she had diabetes but it runs in her family, it’s not serious.” If there would be a health issue, it would probably come from smoking. “She loved to smoke,” said Indai of her friend.

She described their friendship as “deep.” Many of their friends offered her condolences like she was family when Maita died.

“Malalim. She’s a dear friend.”

Thank you for writing this article to honor Maita. I would like to add that Gabriela in 1984 was a product of a many groups and many of us, unnamed, but operated clandestine, were the organizers, coming from various sectors. Maita was part of the founding team of WOMB and she became active in many women’s advocacy as Womb. Lidy Nacpil was part of the youth and active in SCM ( Student Christian Movement). Judy Taguiwalo was still a peasant organizer and much later took the post I vacated in Center for Women’s resources CWR (which i started in 1981). Many wrote the herstory of the women’s movements (there were not one but various women’s movements just as feminism had various mothers). To cite a few, Gilda Cordero-Fernando, Aurora de Dios, Aida Santos.