Book gives voice to the ‘silent generation’ of Filipino Americans

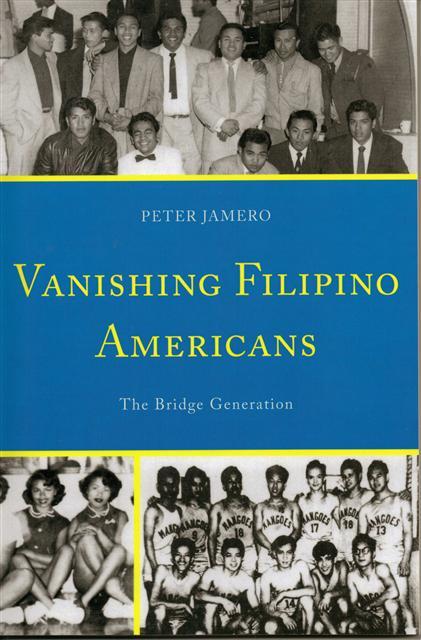

‘Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation’

‘Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation’

By Peter Jamero

University Press of America

May 2011

By Lorenzo Paran III

Any Filipino American worth his salt can tell you about the ‘manong’ generation, the group of mostly single Filipino males that in the 1920s and 30s began the great wave of Filipino immigration into the U.S. But, chances are, he would be unable to tell you about the generation that came next, composed of the ‘manongs’’ children, who would help bring about the acceptance of Filipinos into mainstream American society.

But anyone can be forgiven for not knowing much about these Filipino Americans because they have largely been ignored by historians. That is, until now.

Peter Jamero in his new book, “Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation,” tells their story: who they are, their struggles against isolation and discrimination, their achievements, and where they are now. Jamero gives them the term “bridge generation” because of the role they played as a link from the ‘manong’ generation to later generations of Filipinos in America.

Bridge generation Filipinos, as the book defines it, were those “born in America by the end of 1945 to at least one Filipino parent who immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s.”

Born in often abject conditions in farmworker campos where their immigrant parents settled, these children would grow up with an undeniably American identity without giving up their strong sense of Filipino-ness. Indeed, reaching maturity without the influence and support that Filipinos in the Philippines find in their extended families and regional cultures, bridge generation Filipinos were left to band together, paving the way for the development of a culture that while distinct from that of their parents also was not wholly assimilated into mainstream American life. The result was the birth of a truly Filipino-American culture.

Jamero carefully traces this development by describing the childhood of bridge generation Filipinos and later participation in athletic youth clubs that became instrumental in the formation of vibrant Filipino centers in the farming regions of Northern and Central California where they were found. The Filipino Mango Athletic Club of San Francisco, Stockton Filipino Catholic Youth Society, Livingston Fil-American Youth Club, and San Jose Agenda are just some of the organizations that allowed the youth not only to compete with one another in sports leagues but, as Jamero points out, gave them the opportunity to meet one another and socialize, helping bring about the strong social ties which would bind their generation until the present.While, as Jamero himself says, bridge generation Filipinos never quite equaled the fervor of the ‘manong’ generation’s labor activism, they did make valuable contributions to American and Filipino American life.

World War II was a turning point for the bridge generation — as it was, of course, for other segments of the American population. It was a period when many of its most prominent members (the founders and stalwarts of the youth clubs, for example) would join the U.S. Armed Forces, notably the First and Second Filipino regiments, which helped liberate the Philippines from the Japanese. Rightfully, Jamero points out that for these Filipinos the war served as a coming of age, when they gained a deeper appreciation of their identities as both Filipino and American.

After the war they returned to civilian life, furthered their education and later moved on to, in many cases, storied professional careers. For other bridge generation Filipinos, however, entering the U.S. workforce didn’t come easy. Although by this time, the labor activists (Filipinos, Latinos and others) of the previous generation had undoubtedly had some successes in their efforts to ensure equal rights for all, racial prejudice was still rampant and many bridge generation Filipinos met discriminatory practices in employment and even in housing.

And so the activism continued, although Jamero points out that the bridge generation preferred to continue the fight “from inside” the workplace, and as individuals, not through mass action or protests. Jamero tells of the contribution of Bob Santos, for example. As a member of the Seattle Human Rights Commission in the early 1970s, Santos played a key role in overturning the height requirement for that city’s firefighter candidates, thereby opening up the position to many other potential applicants, especially members of minority groups.

Perhaps that is the greatest achievement of the bridge generation: it made headways in professions that were previously closed to Filipinos and other minorities. In a chapter called “In America’s Workforce” Jamero lists members of the bridge generation who not only joined but also made a name in the field of arts, sports, education, military, business, science and elected office.

This makes “Vanishing Filipino Americans” for even the casual reader a treasure trove of information about Filipino American life as it identifies many notable “firsts” —for example, the first to play Major League baseball, the first to play a part in a major Hollywood film, and the first to be elected governor of a U.S. state. (They are, respectively, Bobby Balcena, who played for the Cincinnati Reds in the 1950s; Pacita Todtod Bobadilla, who had a singing role in the John Wayne movie “They Were Expendable,” and Ben Cayetano, who served two terms as Hawaii governor from 1994-2002. The three are all bridge generation Filipinos.)

The bridge generation is often called the “silent generation” of Filipino Americans. Lacking the fervent and widespread labor activism of the ‘manong’ generation and having left the Filipino centers that they created in their youth for career and family life during the heady days of the civil rights era, bridge generation Filipinos would be consigned to a secondary role as far as advancing the Filipino American cause. Jamero highlights an exception to this relative lack of bridge generation activism: the Filipino American Young Turks of Seattle, a close-knit, politically savvy group that formed in 1970. For more than a decade, the Young Turks played a major role in Seattle’s social and political mainstream. (The group’s efforts, which led to a recognition of Seattle’s Filipinos as a significant force, are the subject of an earlier essay by Jamero, “The Filipino Young Turks of Seattle: A Unique Experience in American Sociopolitical Mainstream.”)

But as the book shows, the bridge generation’s contributions are there. One only has to look. Anyone who does look into the past will be thankful that this band of hardy and ingenious Filipinos in America has found a voice in Jamero and his research. But as he himself says, more work is needed to tell the full story.

Lorenzo Paran III — also known as Third — writes about the Filipino American life on pinoyinamerica.com. His book reviews appear on his blog at filipinoamericanwriter.wordpress.com.

So…why do they call filipino americans manong?