Papa Ping and his one last act of loyalty

By Tony JoaquinWhen I was about 6 years old, I was allowed by my mother to go with my father Porfirio — better known as Ping – to some of his piano playing gigs around Manila.

See, Papa was already a noted jazz pianist long before I was born. In fact, he was known among Filipino jazz musicians as the King of Jazz Pianists sometime in the mid-thirties. Papa however corrected his fellow musicians by saying “the term pianists are those who play classical concerts. I play American jazz so I am called a piano player.”

Good looking, personable and a gentleman when he was playing popular jazz numbers of the era, the ladies would gravitate to his piano and admiringly watch him. I suspect quite a few came rather too close for comfort.

So at a young age, I would visit places such as the Army Navy Club, the Manila Polo Club, the Philippine Sea Frontier, and various diplomatic. The Philippines was a young country then, co-managed by the United States government.

In time, Papa was already leading a 12-piece jazz orchestra with contracts abroad in places like Hong Kong, Shanghai and Japan. The U.S. West Coast ports of San Francisco and Los Angeles were regular destinations.

Papa would often hear from Filipino musicians who ventured in finding work in New York City. In fact, for a long time since the Copacabana Club started operations just before World War II, no non-white musicians were allowed by law to play in any of Manhattan clubs due to the racist attitudes prevailing at the time. Even when Sammy Davis Jr. performed, there were incidents and even brawls sparked by racial slurs from white customers. So much as Papa wanted to try his luck at playing in one of the Manhattan night clubs, he did not entertain the extra effort.

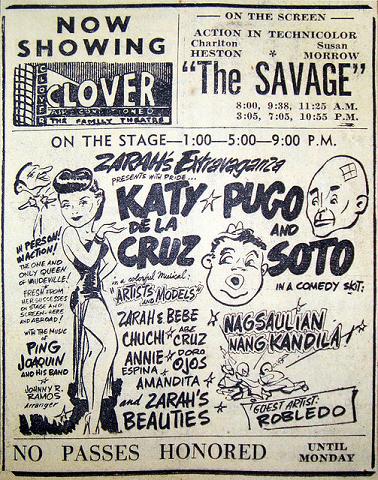

By the late thirties Papa no longer accepted bookings abroad or on luxury liners, but instead decided to be close to his growing family. (I was the eldest and the two girls followed soon after) He eventually settled for contracts to play at stage shows in Manila theaters starting at the Savoy Theatre, which was renamed Clover after the war. This was when moviehouses showed Hollywood films and in between were the live vaudeville stage shows.

By the late thirties Papa no longer accepted bookings abroad or on luxury liners, but instead decided to be close to his growing family. (I was the eldest and the two girls followed soon after) He eventually settled for contracts to play at stage shows in Manila theaters starting at the Savoy Theatre, which was renamed Clover after the war. This was when moviehouses showed Hollywood films and in between were the live vaudeville stage shows.

Tragedy struck when his dear father, Leocadio, suffered a fatal stroke. Immediately, Papa became the sole breadwinner for his mother and nine siblings. Looking back, I might say he did wonderfully well.

He was not much of a typical father. I do not recall too many precious moments with him save for the usual daily trips when he dropped me off at the Ateneo Grade School in Intramuros. Too bad Papa and Mama Sarah could not complete their life together as husband and wife. In 1946 they split up. I was 16 then, Nenita was 14 and Baby was 12. Our young lives were overturned, or so it seemed that time. But we stayed with our mother and managed, under the circumstances, to complete our schooling and continued our adventure in life.

Just years before the Pacific War broke out, Papa worked full-time as a cashier with a cargo moving firm. What I am proud to recall was when suddenly we were at war on December 8, 1941, my father, still with the salaries of employees in his vault, took pains in looking for the addresses of most of the employees and delivering their salaries in their homes! At the time, offices were closed and law and order had begun to break down. Papa could have just pocketed the salaries and no one would have probably missed it. But, he looked at the situation as an opportunity to do one last act of loyalty, and considered it his sense of duty to his position, his firm and his fellow employees.

That made me truly proud of him.

Great story about your Dear Papa!