Patricia Evangelista puts us at the scene of the crime

By Patricia Evangelista

448 pages

Random House

By Tricia J. Capistrano

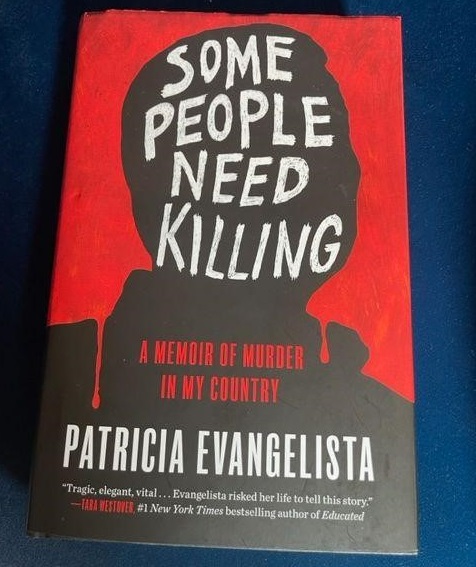

David Remnick, editor of the The New Yorker calls Patricia Evangelista’s book, “Some People Need Killing,” “one of the most remarkable pieces of narrative nonfiction I have read in a long, long time.”

Evangelista, who was born in 1985, was a reporter and then executive producer for ANC, the English language news channel of ABS-CBN. In 2012, when Maria Ressa left ABS-CBN to start Rappler, Evangelista joined as a trauma reporter.

She was a reporter when Noynoy Aquino was president. She wrote about the victims of Typhoon Haiyan in Tacloban in November 2013. Six thousand were reported dead. When Rodrigo Duterte became president, she sat in the Manila Police District Headquarters at night waiting for alerts related to the Duterte drug war. She did not have to wait long. As of January 2023, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights counts 8,663 victims. President Bong Bong Marcos vows to continue the drug war.

Memoir and reportage

“A Memoir of Murder in My Country” is the book’s subheading. In an interview, Evangelista mentions that she initially meant for the book to be more reportorial but through the writing process she said, “I came to understand that I had to take accountability.”

In the first section of the book Evangelista tells us of the journalists in her family and the legacy she had grown up with–she is the granddaughter of journalist Mario Chanco and the niece of Philippine Star columnist, Boo Chanco. Her grandfather was friendly with the Marcoses. She writes about the Marcoses, the Aquinos and the People Power revolution.

A note on “salvage” and “laban”

Logophiles and linguists will love the memoir. Although Evangelista does not claim to be a grammarian, throughout the book she explains the nuances and peculiarities of Philippine English.

Evangelista tells us that “neutralized, encounter, consummated” are all used in Philippine police reports to mean “killed.” Philippine police reports are in English. For those of us who travel to the Philippines often, we are reminded that the word “salvage” needs to be explained. As we know in the Philippines, someone who was “salvaged” does not mean he was rescued.

Another ironic and regretful example is the word “laban.” Evangelista skillfully demonstrates how the word laban, evolved in the last 40 years.

“The electoral deck is stacked against the opposition,” Aquino wrote from his cell in Fort Bonifacio. “But fight we will!” The word for “fight,” in Filipino, is “laban.”

“Lumaban siya.” He fought.

“Lumalaban siya.” He is fighting.

“Nanlaban siya.” He fought back.

Aquino’s new party was named People’s Power–Lakas ng Bayan. Its shorthand was Laban…

“Nanlaban sila“. They fought back.

Thirty-seven years later the word “nanlaban” belonged to the police. “Nanlaban siya,” the cops told us, night after night, bodies at their feet. “He fought back.” “Nanlaban,” under Rodrigo Duterte, did not mean only that a man had fought back. It meant he had fought and died. “Nanlaban” is a judgment and justification, verb and noun, a shorthand for the dead bastards who deserved what they got.

Vivid reminder of old news

For those of us who follow Philippine news, we read the same stories again in Evangelista’s book, but this time with the grit. We read in detail about Efren Morillo, a fruit vendor who went to visit a friend but was there at the wrong time. He was the one shot by policemen, then escaped, and then later arrested, and charged with assault.

Through Evangelista, we get to know Normy, the mother of Djastin Lopez of Tondo Manila, the epileptic who showed up at the train tracks with his hands raised. Three police men took turns shooting, slapping, and then kicking Djastin. Evangelista also tells us the backstory of the secret jail cell found behind a bookcase in a Manila police station.

The stories are appalling, and yet for this reader, it is pitiful that with the constant dump of bad news from back home, they have almost been forgotten.

Preferential option for the poor

She didn’t have to, but what is also admirable is that Evangelista mentions by name and describes the heroic actions of other brave Filipino writers and photographers who document the drug war.

Because of the barbarity of the stories, I found myself taking breaks from reading the book and at the same time, because it’s so beautifully written I wanted to finish and read it again.

What is mentioned in passing however– and perhaps it may need its own book– is how Filipinos, including Duterte, are classist. In Evangelista’s stories, the victims live in shanties. Mayor Duterte’s drug war in Davao and as president of the Philippines targeted the poor. Evangelista is a masterful writer. And what is also remarkable is that for Duterte, who sells himself as the common man, the “some” who need killing are the poor.

Support independent bookstores! Bookshop is an online bookstore with a mission to financially support local, independent bookstores. Click here to go to TheFilam.net Bookshop page. We get a small commission every time a book is sold through the page.

© The FilAm 2023