St. Malo, Louisiana Filipinos: Separating fact from fiction

By Lynn Topel

There have been claims that in 1763, in a little-known fishing village on Lake Borgne in Louisiana called St. Malo, Filipino fishermen built houses on stilts, learned to live with the elements, and energized the local shrimp industry. Nearly 9,000 miles away, Filipinos in Louisiana were a long way from home.

However, as historians and researchers dug through the scant records available about that time period, there seems to be little evidence to back up this oft-repeated piece of trivia.

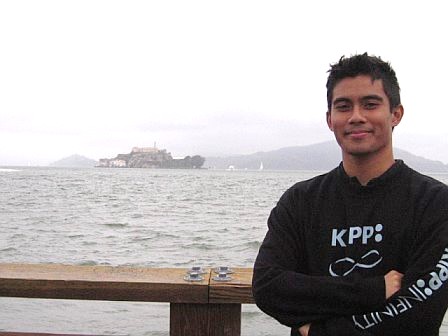

Though it is very likely that Filipinos jumped ship when their vessels docked on the New Orleans port, the earliest account that can be found on this is not till the 1830s—more than 60 years from the alleged 1763 founding of St. Malo as a Filipino fishing community. This is not to say that these communities didn’t exist at that time. Randy Gonzales, associate professor of English and assistant department head at the University of Louisiana of Lafayette, explains: “1763 is wrong. It is based on Louisiana becoming part of New Spain, but in 1763 this was only on paper. Spain didn’t take full control of the territory until 1769 as there was a rebellion by French planters. This misinformation has been repeated and shows a lack of awareness of Louisiana history… The first Filipinos in Louisiana were probably in other locations before they went to St. Malo.”

Filipinos in the West

For 250 years starting in 1565, ships called Manila galleons sailed between Mexico and the Philippines. Spanish merchants and traders brought with them the much-coveted spices (and other exotic goods such as silk and ivory) from the East to sell in the West. Other European merchants, like the British, also stopped at the Philippine ports to stock up on sugar and abaca, or manila hemp.

Many of the ships’ sailors were Filipinos who already had their sea legs from working as fishermen and were already adept at navigating the many islands that make up the Philippine archipelago.

Despite their seafaring skills and service to their European ship captains, Filipino sailors were only paid a fraction of the wages that their European counterparts received. Conditions onboard were unsanitary and harsh, on top of the fact that the journey was already long and dangerous. To avoid desertions and mutinies, the seamen’s full pay was not given till the end of the journey.

Because conditions were so horrible, some Filipino seamen decided to forfeit their pay and jumped ship. Many were able to blend in with the locals in Mexico as they knew how to speak Spanish. Some even ventured further into the Spanish-controlled territories of California.

An Island Refuge

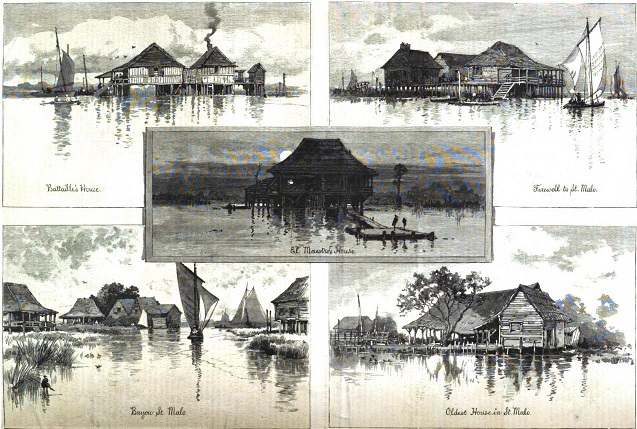

St. Malo was home to the Choctaw Indians and Black slaves with the island being named after Juan San Malo (Jean St. Malo to the French), who was a leader of a group of around 50 maroons, or Africans who escaped slavery. He and his group of cimaroones, as the Spanish called them, ruled the roost in these marshy wetlands until his capture and death by hanging on the French Quarter in 1784.

In an essay by historian Michael Menor Salgarolo, Ph.D. entitled “The First Asians in the United States: Filipino Sailors in the Bayou,” he states that Filipinos who deserted their ships on the New Orleans port occupied “the village at St. Malo at some point in the nineteenth century.”

These mosquito-infested, hurricane-prone islands were not the most habitable place to live. Yet the “Manilamen,” as the Filipino sailors came to be called, never felt more at home. They were already used to the Eastern Hemisphere typhoons, and probably used their skills in making fishing nets to make a version to ward off mosquitos as they slept. The fishermen lived in wooden houses built on stilts, or the bahay kubo. This early account of a settlement was first reported in Harper’s Weekly by Lafcadio Hearn, a journalist who visited St. Malo in 1883 and recorded that the settlement of “Malay fishermen” had been in existence for 50 years from that time, setting the existence of the Filipino community in the 1830s, right about the mid-19th century.

The Dried Shrimp Enterprise

The Filipinos earned their livelihood by fishing, harvesting shellfish, and using their knowledge of drying shrimp in order to make these crustaceans last a little longer, in an age when modern refrigeration had not yet been invented. The Filipinos had established another settlement on Barataria Bay, which was called “Manila Village,” and it became one of the communities with a thriving shrimp-drying business.

In a process that involves boiling the shrimp in brine, these were then dried out on wooden platforms. By the third day, the shrimp’s shells were removed via a process called “shrimp dancing”—the “dancers” walked over the shrimps causing the peels to be separated from the meat. Both of these may be collected separately as the powdered shells may still be used in cooking sauces, fertilizers, and hog feed. Initially, these salty shrimp were mainly used for the Filipinos’ subsistence. Later, with the help of Chinese traders, they found their way into mainstream Louisiana cuisine and are now sometimes used as an ingredient in dishes like Gumbo and Jambalaya.

(Nearly) Wiped Out

In 1906, the village of St. Malo was destroyed by a hurricane. Some accounts have 1893 as the end of St. Malo. However, in 1906, another hurricane battered St. Malo, and news reports indicated that 100 fishermen, who had stayed on from the last hurricane, perished. Although other hurricanes hit the island years later, that was the last of any reports of a village existing on St. Malo, explains Gonzales, who pegs the end of the community in 1906. Those who survived moved on to Manila Village on Barataria Bay and Clark Cheniere, another bayou community.

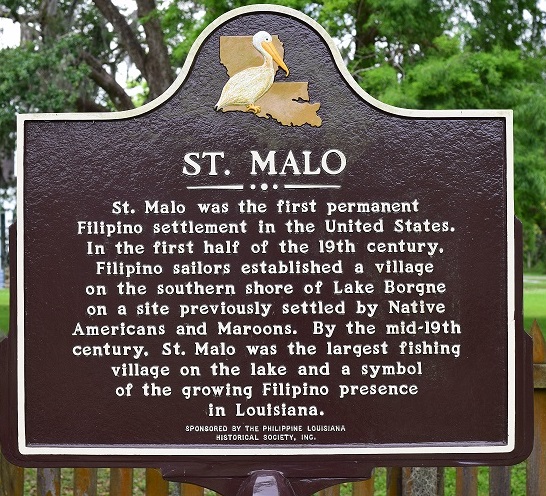

This piece of history would have been nearly wiped out if not for the efforts of the descendants of those early Filipinos and Filipino Americans who reside in Louisiana today. In November 2019, a historical marker, which was requested by the Philippine-Louisiana Historical Society, was finally unveiled to mark the first permanent Asian settlement in America. The marker uses the “first half of the 19th century” as the establishment date, basing it on the first written record of the settlement—still making it the earliest of its kind. It is a proud testimony of the Filipinos’ place in U.S. history as well as their many contributions to Louisiana life and culture.

© The FilAm 2023