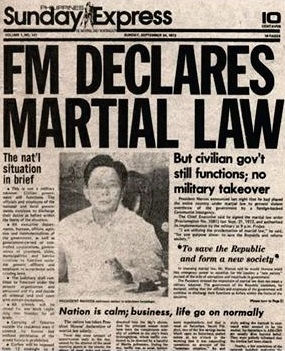

Martial law: The past is prologue

By Allen Gaborro

Filipinos have little patience for the past. They keep up the appearances of speaking to the past, of communing with it.

However, Filipinos under this cover, to source a postmodernist’s response, “devour its absence”. When are Filipinos going to realize that their democracy was not exactly created equal with others, that this precarious state would cast the country forward into the shadow of something as barren of righteousness and freedom as Marcos’s one-man rule?

It was 51 years ago that a gambit butchered Filipinos’ sunlit democracy and splintered it into the cavernous depths of a dictatorship. The Philippines contracted then as its moral and democratic circumference became no longer possible to ascertain. How easy it has been for Filipinos to move on without fully absorbing that well-chronicled history.

A lot has been said and written about martial law and how it dehumanized everyday life in the Philippines. This is telling because it allows one to plead the case that the memory of martial law has not been prima facie left by Filipinos to twist in the wind, that the remembrance of it by Filipinos of all stripes has not entirely abated thanks to the flowing pens and fearless voices of writers, artists, thinkers, and dissident activists who defied the regime.

Cradled however in a broad, mesmerizing ideal– a modern ideal that estranges them from yesterday and raises expectations of something better over the horizon– Filipinos to a large extent rarely pause to make out the contempt that the illustrious cast of the martial law initiative continue to have for their rights and liberties.

After freedom reigned again in the Philippines, the anti-Marcos economic and political elites descended back into the familiar complacency and profitability of the status quo and instead of leading them to repent and reform, allowed the villains of martial law to receive the political and economic rewards of evading punishment for their crimes. Now as a result, many of the martial law perpetrators are in positions of power today, putting their political successors up to the same machinations that filled their own careers with ulterior intent.

That the memory of martial law hasn’t inextricably lodged itself into the minds of Filipinos has less to do perhaps with shutting down an unguarded, sobering view of a traumatic myth of balance and order than it does with Filipinos afraid of having to, as Nietzsche held, stare into the abyss because it would stare back.

Maybe Filipinos should stare into the historical abyss of martial law more often so that they won’t have any reason to be caught unawares when it rears its head once again.

This piece originally appeared in Allen Gaborro’s website “Narratives of Resistance.”