Who is Raymundo Mata and what is his role in PHL revolutionary history?

By Allen Gaborro

To even begin trying to understand Gina Apostol’s perplexing, historical, and political spectrum of a novel about the Philippines during its pre-turn of the century revolutionary era, “The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata,” a reader has to get out from under the tried and true empirical norms of the classical literary universe and take a leap into the murky zone that lies between fact and fiction, culture and politics, method and disorientation, history and mythmaking, subjective memory and objective past.

Apostol writes in the author’s note that “This book [Raymundo Mata] was planned as a puzzle: traps for the reader, dead-end jokes, textual games, unexplained sleights of tongue.” However, despite taking the notion of poetic license to an entirely different level, Apostol remains loyal to the anchor that is Philippine history: “At the same time, I wished to be true to the past I was plundering.”

There are a plethora of fiction and nonfiction works about the Philippine revolutionary period which saw the end of Spanish rule. But while “Raymundo Mata” is put together from the heterogeneous material of the Philippine revolutionary generation, the novel is no ordinary literary memorial to that time.

As stated in a description of the book, Apostol the novelist is the proprietor of “anarchic modes of narrative” in this fictitious chronicle of an invented Filipino revolutionary.

Who is Raymundo Mata? To answer that question, Apostol constructs a multivocal, multiperspective journal of this character’s life. It follows then that the further one reads into the novel, the more labyrinthian it becomes to pin Mata down. We discover that Raymundo Mata is man of several parts: at once a man of science and verse, of sentimentality and politics, he is a purblind revolutionary and bibliophile who “From birth…was immersed in the world of make-believe.”

Apostol’s contrived translator Mimi C. Magsalin forewarns that “The man you will find in the manuscript has no approximate precursor in the annals of the [Philippine] revolution, perhaps even of humankind.” Magsalin is also one of the memoir’s footnote contributors. There are two others, Estrella Espejo and Diwata Drake. Their collective input paves the way for skepticism, disagreement, and hermeneutical contention. As each contributor takes turns trying to talk over the other, their hodgepodge volleys of assertions are untethered at times to calm deliberation or expression.

While Mata’s life chronicle is tilted towards being a disjointed, centrifugal text that is, as Magsalin notes, “linguistically deranged” and potholed with “spastic code, squiggles and symbols” that were “halting” and “hallucinatory”, the novel does converge around the Philippine Revolution which started in 1896.

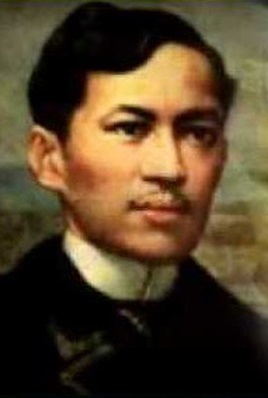

Whenever the topic of the Philippine Revolution is broached, the historical figure of Jose Rizal is inevitably found at the center of any such study or discussion. Romanticized by Filipinos as a national hero, Rizal is paid the proper respect by Mata (“Ah, Rizal. I met him you know.”) by having perused through the latter’s iconic postcolonial novel “Noli Me Tangere.” This in turn inspires Mata to seek out the future national martyr for himself.

Rizal’s presence reverberates throughout much of “Raymundo Mata.” This is a reflection of the man’s lofty stature in Philippine history. Combining witticism and nationalistic prestige, Apostol writes to that effect: “Two things shape the Filipino; puns and Jose Rizal.”

“Raymundo Mata” directs our gaze towards the Filipino struggle for nationhood which was thwarted by America’s expansionist ambitions. Filipinos were able to expel the Spanish only to have their polity subverted by another colonizer, the United States.

In the novel, America’s colonial encounter in the Philippines comes flooding back into the social, cultural, historical, and psychological spaces that are interlaced into the Filipino identity as a people and as the body politic.

Apostol compels both her Filipino and American audiences to reexamine their joined history without past preconceptions or misrepresentations. She tacitly interrogates, through Mata’s remembrances and her trio of commentators, America’s openly-altruistic but opportunistic and violent crusade to “civilize” the Filipinos after the Spanish were expelled.

Manifestly worthy of being called an erudite confluence of writing skill, organization, and compilation, “Raymundo Mata” is deserving of being raised as a dynamic living history of a revolutionary Philippines.

Support independent bookstores! Bookshop is an online bookstore with a mission to financially support local, independent bookstores. Here is a link to TheFilam.net Bookshop page.

(C) The FilAm 2023