New president’s name should be Ferdinand Romualdez Tabuebue Jr.: Book

By Todd Sales Lucero

Published August 2020

By Tricia J. Capistrano

In a parallel universe, last June’s presidential inauguration would have the Philippines welcoming a President Ferdinand Romualdez Tabuebue, Jr. This is because, according to genealogist, Todd Sales Lucero, after the Claveria surname decree of 1849, the Marcos family adopted the name “Tabuebue.”

According to Lucero, President Marcos Jr.’s grandfather, father of President Ferdinand E. Marcos, born on April 21, 1897, was officially registered as “Mariano Tabuebue.” It seems that during the American colonial period, Sales writes in his website, www.Filipinogenealogy.com, “the family reverted to the name “Marcos.”

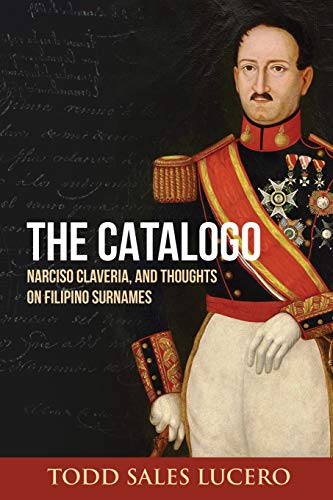

Todd Sales Lucero, is a professional genealogist based in Davao and Cebu City. In 2018, he published the book “The Catalogo Narciso Claveria and Thoughts on Filipino Surnames.” In the book’s notes, Lucero writes that his version is an answer to former Philippine National Archives Director Domingo Abella’s 1973 reprint of “Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos” which is no longer in print. The original Catalogo Alfabetico is a list of surnames distributed by Narciso Claveria, the governor general of the Philippines from July 1844 to 1949.

Choosing a surname

Before the Catalogo, naming practices in the Philippines varied. Pre-colonial writers observed that mothers chose the names of children–often inspired by nature or a trait–and then the child’s name changes once she or becomes a parent. For example, Ana, the mother may choose the name “Malacas,” in the hopes that the child will be strong. Ana then becomes “Ana Ynani Malacas,” to mean Ana, the mother of Malacas.

In some provinces, descendants of ancient Filipino nobility used the names of their clans, like Gatmaitan, Gatbonton. “Gat” meant “prince” or “great lord.” And then some families, because of their Spanish or Chinese lineage, followed their parents’ practices and adopted their parents’ last names.

In the decree, Claveria writes that the Catalogo’s purpose is to aid in “the administration of justice, government, finance and public order.” The composition of the list includes Spanish surnames and indigenous names collected by the Reverend Fathers Provincial of the religious orders. There are 53,517 surnames in the Catalogo. Unfortunately, there is nothing in the decree that mentions what one can do if she or he does not like the last name chosen by their parent or grandparent. Perhaps children truly did not disagree with their elders then?

The role of school teachers

The book is short but contains substantial information. In the chapter, “Claveria and the Myth of Spanish of the Ancestors,” Lucero explains the repercussions of the decree and why even if we may have been told that we are descendants of a Spaniard, that we may not be, or that even if a friend has the same last name–because our forefathers chose their surnames from a common list distributed across the country–that you may not be related.

Also of special interest are the chapters on “Claveria’s Surname Decree,” and “Dissecting the Claveria Decree and Answering Some Questions About It.”

The former chapter reprints instructions on how the list should be distributed. The third decree gives the following instruction: “Each cabeza shall be present with the individuals of each cabeceria, and the father or the oldest person of each family shall choose to be assigned one of the surnames in the list which he shall then adopt, together with his direct descendants.”

School teachers had a special role in the dissemination of the last name. The eleventh decree states that “School teachers shall have a register of all the children attending school with the names and surnames, and shall see to it that they shall not address or know each other except by the surname listed on the register which should be that of the parents. In case of lack of enthusiasm in compliance with this order, the teachers shall be punished in proportion to the offense at the discretion of the head of the province.”

The instructions, reprinted in English, are thorough. And for those who can read Spanish, Lucero includes a photograph of the original.

In the chapter, “Dissecting the Claveria Decree and Answering Some Questions About It,” Lucero delves into the application of the 24-point decree. Although the decree says “the distribution of the surnames must be made by letters in the appropriate proportions,” Lucero includes the results of his research. He found that in certain provinces like Oas, Albay, 72% of surnames begin with “R” and other irregularities.

In an online seminar last March, Lucero shared that perhaps due to lack of resources, it was difficult to distribute across the islands the page and pages of surnames.

In the same chapter, Lucero writes about how although the decree says “natives of Spanish, indigenous, or Chinese origin, may retain it and pass it on to their descendants,” many families, including the Philippines’ national hero’s family, changed their last name. Rizal’s Chinese ancestor was Domingo Lam-co. The family changed their name to Mercado. Lucero writes the family petitioned to change their name numerous times to Rizal but was denied. Jose was the first to use the family name, “Rizal,” when he enrolled at the Ateneo de Municipal in 1872.

In the book, Lucero also includes the genealogy of several prominent Filipino families. He also shares tips on how to research your own family’s lineage.

This request may be out of scope but Lucero has already whetted this reader’s appetite. With our current digitized and globalized world and for the readers of this community magazine, I wish that in a future reprint, Lucero would include recommendations on how to research one’s family history online.

173 years later

According to Lucero, Claveria was a passionate and effective administrator and his travels across the Philippines affected his health. Claveria died in 1849 shortly after the decree. Historians note that because of the slow communications and travel during that time, the decree took effect one year later. Claveria did not even live to see it promulgated across the archipelago. One hundred and seventy-three years later, the Philippines is now a country of 110 million, and Filipino people with Spanish last names have journeyed all over the world. I wonder if this was a possibility that crossed Claveria’s imagination.

Tricia J. Capistrano’s essays have appeared in The Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Philippine Star, TheFilAm.net, and Newsweek. She is the author of “Dingding, Ningning, Singsing and Other Fun Tagalog Words.” Her essays were chosen as the Best Personal Essay by the Philippine American Press Club in 2017 and 2018.

Support independent bookstores! Bookshop financially supports local, independent bookstores. “The Catalogo” and “You’ve Changed” are available on TheFilAm.net’s Bookshop page.