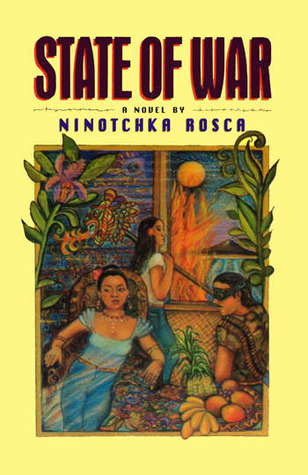

Ninotchka Rosca’s ‘State of War:’ Political corruption of the present echoing the past

By Allen Gaborro

As the 2022 Philippine presidential elections approach this summer, the specter of the return of the Marcoses to the apex of political power is rearing its head. It is for this reason that Ninotchka Rosca’s classically incendiary novel, “State of War,” holds as much social, cultural, and political currency today as it did when it was first published in 1988.

Composed in the wake of the 1986 People Power revolt that overthrew the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, “State of War” is sharp in tone and penetrating in mood and content. It was written as a reminder to Filipinos of the moral darkness engendered by the excesses of Marcos’s martial law regime, the crippling effects of which are still with Filipinos today.

The novel’s redolent aura is interwoven with themes of political subjugation, corruption, and violence in the Philippines. The Marcoses are never directly mentioned in “State of War,” but it is clear who Rosca is alluding to in her narrative when she refers to the “Commander” and his “clan.”

“State of War” can be a dense and deviating text at times, but it retains a steady symmetry by utilizing the concept of a festival as an intensely personal and social allegory. Rosca illustrates the festival—which is based on the annual Ati-Atihan celebration that commemorates pagan and Christian traditions—with a convivial familiarity but more significantly, with an iconoclastic spirit, and a murderous intent.

Three of the festival’s participants form the young trio of dissonant characters whose fortunes ebb and flow as the story moves on. There is Adrian Banyaga, heir to the Banyaga landed elite. Then there is the subversive Anna Villaverde, a trauma victim of military terror. Rosca describes her as “among the powerless of powerless.” Finally, there is the situationally ethical of the three, Eliza Hansen. She devotes herself to romantically pairing Adrian and Anna. At the same time, Eliza serves at the pleasure of the highly-placed Colonel Batoyan and the zealous Colonel Amor as paramour to both.

Rosca fixes the drama of “State of War” in a wider historical lens. Centuries of Spanish and then American imperial rule stunted and distorted the idea of an autonomous Filipino national identity. A tragic consequence of that colonial experience has been a trail of blood and tears. Rosca writes:

“The americanos dealt with the [Philippine] insurrection with great efficiency, torching villages and shoving two hundred fifty thousand corpses into mile-long graves, both men and women.”

Rosca does not spare the Spanish in portraying an instance of their imperial immorality against the indigenous populace, especially against the native women. In a scene suggestive of Padre Dámaso in José Rizal’s “Noli Me Tángere,” Rosca trains the reader’s attention on what might be described as a Spanish friar’s rape-with-consent of a 14-year girl:

“[She] knew enough not to resist the priest…She yielded her virginity on a bed of pebbles and curled arms and legs tightly about the pain of the unholy entrance.”

Rosca’s female characters are a distinctive aspect of “State of War.” From Anna Villaverde to Eliza Hansen to the subsequent grand dame of the story, Maya, the women in the novel have something in common other than complicated matters of the heart. Rosca acknowledges the pivotal role of her female personages as she takes the conception of an independent, coequal, emancipated Filipina woman to another level.

In a passage in which she pays homage to the exploited and oppressed Filipinas of history, Rosca elevates them in a precolonial, babaylanic, animistic image of respect and authority:

“…the voices of other women who spoke of a time when the world was young…when women walked these seven thousand one hundred islands with a power in them…for women then were in communion with the gods, praying to the river, the forest spirits, the ancient stones…They walked with wisdom.”

With a symbiotically omnipresent air of portent and solemnity, to say nothing of an indebtedness to Mikhail Bakhtin’s idea of the carnivalesque, Rosca reinscribes in “State of War” a Philippines that once was. As a result, there is a looming question issuing forth from her work: are Filipinos condemned to repeat their mistakes or are they prepared to restore the foreclosed possibilities of their nation?

© The FilAm 2022

Support independent bookstores! Bookshop is an online bookstore with a mission to financially support local, independent bookstores. Below is a link to TheFilam.net Bookshop page.