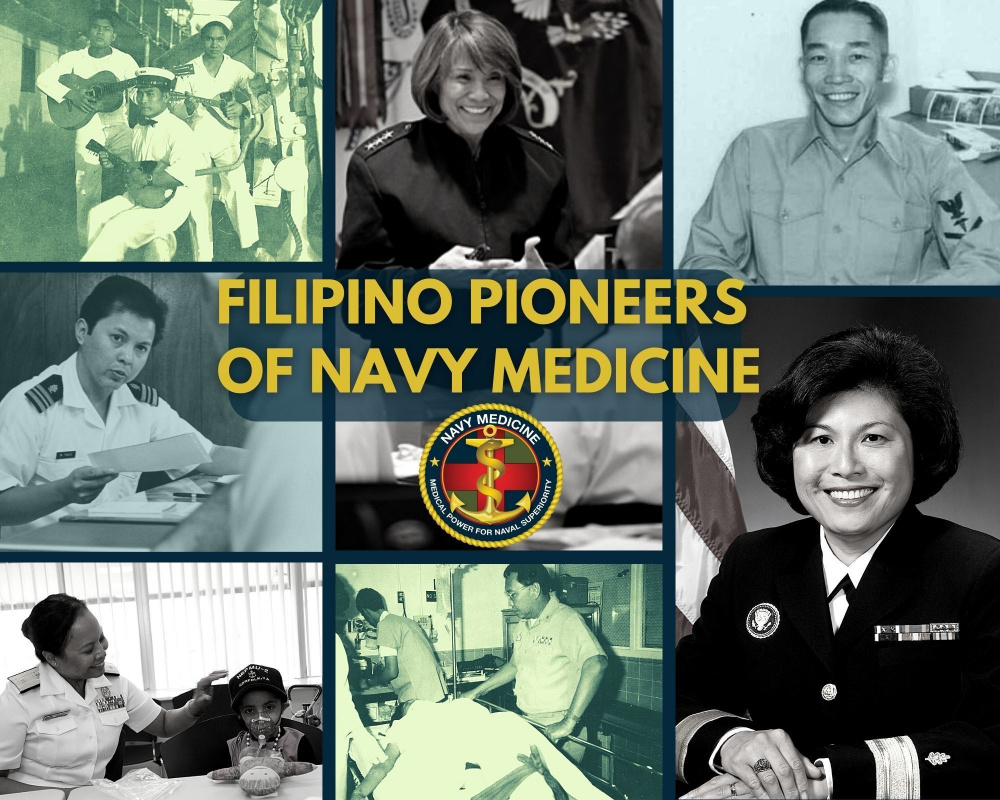

The Filipino pioneers of Navy medicine (Part 1)

By Andre Sobocinski

Filipino Americans have long played vital roles in the U.S. Navy and have helped to shape Navy Medicine through their numerous contributions as leaders, healthcare providers, medical administrators, and scientists.

The story of Filipinos in the Navy began in wake of the Spanish-American War after Spain ceded the Philippine Islands (P.I.) to the United States. In 1901, President William McKinley issued an Executive Order permitting Filipinos to enlist in the Navy. Among those early Filipino pioneers were Teleforo Trinidad, the Navy’s first Filipino Medal of Honor recipient (1915) and David Nepomuceno, the first Filipino Olympian (1924).

After the Philippines gained its independence from the United States in 1946, the U.S. Navy—still entrenched in the country—established an agreement allowing Filipino nationals to enlist. With few exceptions most Filipinos were limited to the Navy’s steward branch through the 1960s.

This is a history that is personal for Rear Adm. Eleanor Concepcion “Connie” Mariano. The trailblazing naval officer and White House physician was the daughter and niece of Navy stewards. She was born at Naval Station Sangley Point while her father was detailed as a steward to a flag officer.

“Joining the U.S. Navy as a young man was certainly a step up for my father even if the Filipino stewards, especially on shipboard deployment, were like glorified house boys,” said Mariano. Whether shipboard or ashore, stewards were typically engaged in the tedious and menial tasks of cleaning, cooking, preparing meals, and making beds. Those stewards and mess attendants assigned to senior medical officers, hospitals and hospital ships in the first decades of the twentieth century represent the first Filipinos in Navy Medicine.

The Northcott Brothers — Corpsmen and POWs

The Northcott brothers—John (b. 1918), Robert (b.1920) and Thomas (b.1921)—were three seamen apprentices-turned hospital corpsmen who miraculously survived a gauntlet of disease, torture and deprivation over their first years of naval service. They were born in what was still the U.S. Territory of the Philippines to a British-American father and a Filipino mother.

The brothers enlisted in the U.S. Navy in January 1941 and were assigned to USS Vaga (YT-116), a tug used for patrolling the Filipino coastline from the Cavite Navy Yard to the island of Corregidor. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines in December 1941, the Northcotts helped scuttle the Vaga off Corregidor and joined a naval unit attached to the 4th Marine Regiment in defense of Corregidor until their own capture on May 6, 1942.

Along with fellow defenders of Corregidor, the Northcotts were transferred to the Bilibid detention facility in the heart of Manila. Throughout the Japanese occupation, Bilibid was used to process thousands of American, Filipino, Dutch, British, Australian and Kiwi prisoners to labor camps throughout the Philippines and Japan. Among Bilibid’s internees were physicians, dentists and hospital corpsmen who had once staffed the U.S. Naval Hospital Canacao. Despite suffering from tropical disease, malnutrition and lacking sufficient medical supplies and equipment, the personnel of this “hospital unit” continued to treat the sick and wounded, operating what was termed the “Bilibid Hospital for Military Prison Camps of the Philippine Islands.”

The Northcotts were employed as “sick-bay strikers” working Bilibid’s makeshift hospital wards and receiving special instruction from doctors and pharmacy warrant officer in nursing, first aid, and administration. Bilibid’s hospital unit even had regular examinations for rate advancement. John, Robert and Thomas would each be examined and promoted to pharmacist’s mate third class in November 1942.

In spite of many setbacks—including bouts of dengue fever and amebic dysentery—the Northcotts remained on near-continuous duty. As it was later reported in their Bronze Star citations, each continued their duties as corpsmen despite limited rations, constant harassment by guards; and each willingly shared their meager supplies of food, clothing and other necessary articles to less fortunate and ill prisoners.

On October 21, 1943, John, Robert, and Thomas were among 228 Bilibid prisoners “drafted” for work detail on an old rice farm in Cabanatuan, 90 miles north of Manila. There the brothers remained working in malaria-rife conditions until they were finally broken up. John and Thomas were sent to mainland Japan aboard the “hell ship” Oryoko Maru. Robert remained at Cabanatuan until his liberation.

In December 1944, John and Thomas were loaded into the ship’s cargo hold with 1,617 others. Each were required to subsist on one-fifth of a canteen cup of steamed rice, two ounces of water, limited air, and no sanitary facilities. On that first night at sea 70 POWs would suffocate or die of dehydration. Two days later, while off Olongapo, the ship was strafed and bombed by aircraft from USS Hornet (CVA-8) killing another 270 prisoners. Those lucky enough to survive the sinking were herded onto a cattle boat which would be sunk off the island of Formosa killing an additional 268 prisoners. The remaining POWs were then loaded onto a third ship. Over the course of its 17-day voyage an additional 656 prisoners would die of exposure, starvation and disease before arriving in Japan on January 30, 1945—the very same day Robert Northcott was rescued from Cabanatuan. John and Thomas Northcott would spend the remainder of the war at prison camps in Japan before finally being liberated in September 1945.

After the war, the Northcotts remained in the Navy. John and Robert served through 1961, rising to the rank of Chief Hospital Corpsman (HMC). Thomas was promoted to HMC in 1950 and served with the First Marine Division in Korea until wounded in action in September 1950. He was later awarded the Silver Star for his actions in theater.

On January 6, 1942, 12 nurses were taken prisoner by the Imperial Japanese forces in the Philippines. Eleven of these nurses were U.S. Navy; the twelfth was a Filipino civilian nurse named Basilia Torres-Steward.

Mrs. Torres-Steward was married to a U.S. naval civil engineer corps officer, who was also interned during the war. During a 37-month imprisonment these 12 nurses (sometimes referred to as the “12 Anchors” for their strength and resilience) were held captive at Santo Tomas and later Los Baños prison camps. Despite suffering from the same deprivations and nutritional diseases as their fellow prisoners, Basilia Torres-Steward and the Navy nurses continued to care for the sick and injured. For many of the prisoners these nurses were the embodiment of selfless devotion and helped keep morale afloat during the lowest points of captivity. After repatriation, Mrs. Torres-Steward moved to the United States where she became a naturalized citizen.

André B. Sobocinski is a historian at the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. This article was originally published by the Department of Defense DVIDS Media.

NEXT: Expanding roles for Filipinos in Navy medicine