Why illegal immigrants don’t seek treatment for COVID-19

By Sunita Sohrabji, India-West

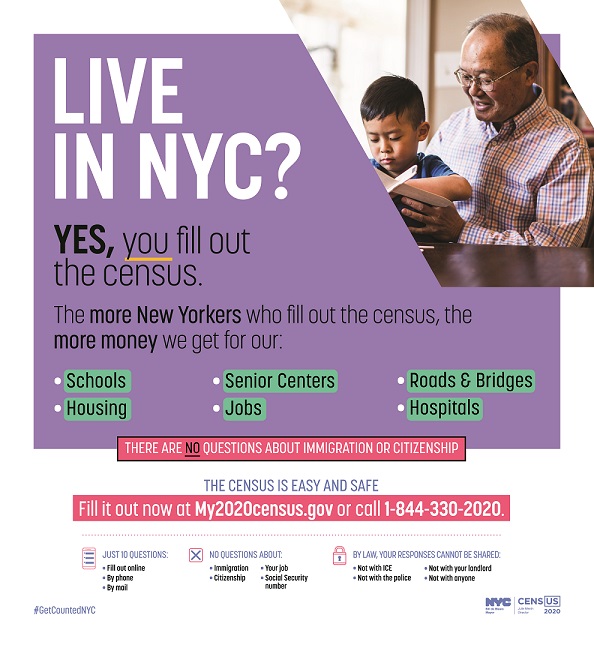

Immigrant communities fear to seek treatment for COVID-19 because of the new public charge rule that says those who seek any form of federal public aid could be denied permanent status in the U.S.

Dr. Daniel Turner-Lloveras of the Harbor UCLA Medical Clinic made this remark at a webinar organized by Ethnic Media Services and sponsored by the Blue Shield of California Foundation.

But in a March 27 alert, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services stated that: “The Public Charge rule does not restrict access to testing, screening, or treatment of communicable diseases, including COVID-19. In addition, the rule does not restrict access to vaccines for children or adults to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases.”

The March 27 advisory also stated that there might be an exception with regard to the receipt of certain cash and non-cash public benefits. “The rule requires USCIS to consider the receipt of certain cash and non-cash public benefits, including those that may be used to obtain testing or treatment for COVID-19 in a public charge inadmissibility determination, and for purposes of a public benefit condition applicable to certain non-immigrants seeking an extension of stay or change of status,” stated the agency.

About 43 percent of undocumented immigrants have no health insurance, said Turner-Lloveras. “We cannot contain a virus outbreak by providing care to only some of the population. We cannot successfully contain an outbreak if there are those among us who are afraid to seek care,” he said.

Public health innovator Rishi Manchanda, founder of HealthBegins, said the pandemic disproportionately affects immigrants and people of color. Psychiatrist Sampat Shivangi, currently serving on the Trump administration’s Council for Mental Health and Substance Abuse, spoke about the psychological effect of self-isolation and the possible surge in substance abuse.

Veteran activist Manju Kulkarni, executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council (A3PCON), briefed reporters on the rise of hate crimes against the Asian American community in the wake of the pandemic.

Dr. Tung Nguyen of the University of California, San Francisco said he has “never seen doctors so scared by an infection. We could be looking at a million infections by next week and four million by next month.”

The virus is deadly: 15 to 45 of every 1,000 infected people will die of a COVID-19 related illness, Nguyen said, noting that the elderly are particularly vulnerable. No vaccine exists for the disease, and the U.S. is still 12-18 months away from developing one. No cure exists, said medical experts on the panel.

“You need to just stay home,” Nguyen stressed. The most effective methods to steer clear of the virus are social isolation and avoiding touching objects and surfaces. For communities of color and immigrants, who tend to live in multigenerational households, it’s imperative that people who must leave the household for work wash up and change clothes afterward, before engaging with their families again. The virus may be in the air for up to three hours. It can live on cardboard for up to 24 hours and on plastic and steel for 72 hours, the UCSF physician said.

New York City is currently experiencing the worst of the pandemic, Turner-Lloveras said, and its overloaded hospitals lack medical supplies to treat all ill patients. California hospitals, which had an extra week to prepare, may be better-equipped to manage the surge. They are trying to triage appropriately, using telemedicine and other resources to avoid a crush of people coming in at once.

Turner-Lloveras has worked in low-income communities in Los Angeles and advocates for hospitals to be “ICE-free zones” that limit immigration agents’ access so they cannot arrest and detain people seeking medical care. He also spoke out against the overcrowding at ICE detention centers that can increase the community spread of the virus.

Manchanda also has worked in South Central Los Angeles’ low-income communities. He told reporters that the pandemic disproportionately affects the economic well-being of people of color and the immigrant community as well as their health.

“It’s hard to not work for many communities of color. Lower wages and insufficient insurance coverage limit their access to treatment and often forces them to work even while ill, increasing the risk of exposure to the community,” he said. Also, many minorities live in large cities, frequently in public housing, placing them at a greater risk for infection. And members of ethnic communities often work in front-facing jobs, such as grocery-store clerks, and take public transportation to get to jobs, resulting in higher rates of exposure. — Ethnic Media Services

© The FilAm 2020