The Barrettos and the privilege of behaving badly

By Joel David

Since celebrity scandals observe the same cycle of fostering fatigue among the public after a period of intense engagement, don’t be surprised if the latest Barretto family intrigue has mellowed, if not dissipated, by the time you read this. Hence Gretchen Barretto did not feel the need to use another family name when she was launched as part of the second batch of Regal Babies. Unfortunately, the rival Viva Films studio had just launched its monstrously successful all-male Bagets batch, and Rey de la Cruz had an all-female troupe, the Softdrink Beauties, claiming whatever (frankly prurient) interest could be generated in good-looking women.

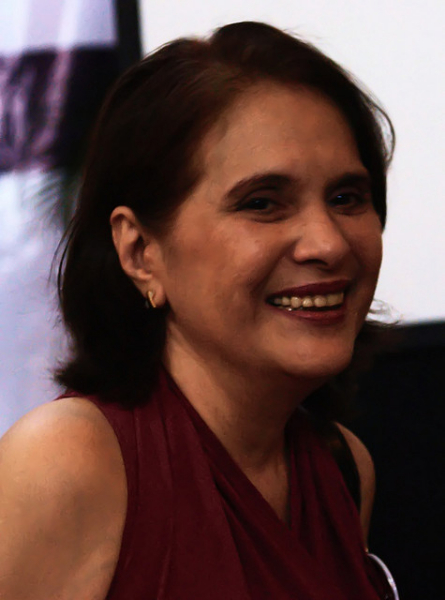

So the Regal Babies II were destined for obscurity, with a bravely determined Gretchen languishing in supporting roles (barely noticeable in Lino Brocka’s Miguelito: Ang Batang Rebelde [1985], for example), banking on her classy features but limited by her narrow range as a performer. By the 1990s, she had shed enough of her premature flab and gained enough height to look alluring enough for male-gaze purposes. Robbie Tan, founder-manager of Seiko Films, correctly deduced that the public had tired of sex sirens who looked and behaved like they came from the wrong side of the tracks. He devised a series of projects that objectified seemingly unattainable porcelain beauties led by Gretchen, turned his outfit into a major player in the process, and made the first Barretto star.

Another Barretto took Gretchen’s place as constant second-stringer: Claudine, her younger sister. Unlike her predecessor, Claudine handled her years of relative obscurity as an opportunity to hone her performative skills. Her walk in the sun had a healthier component to it, by conventional moralist standards: she came of age when romantic comedies succeeded in displacing all the other then-profitable local film genres: horror, action, comedy, even her elder sister’s soft-core melodramas, and managed to prove her mettle alongside the peak capability of Vilma Santos.

An accident of fate propelled Claudine to a stature never attained by Gretchen. It was, unfortunately, a tragedy, the first indication that the Barrettos could only best thrive on the wings of bad news. Just as Gretchen became a star by shedding her clothes, Claudine captured the public imagination when she broke up with her illustrious boyfriend, Rico Yan, grandson of a former army chief and ambassador during the presidency of Ferdinand E. Marcos. The heartbroken beau repaired to a Palawan resort, where he failed to awaken on Easter Sunday of 2002, after a night of heavy drinking.

This made of Claudine an even bigger star than her Ate Gretchen, and acrimonious vibes from the sisters’ perceived rivalry began getting airtime, with then-incipient social media paying due interest. Gretchen became the constant partner of businessman and media mogul-aspirant Antonio “Tonyboy” Cojuangco, while Claudine linked up and eventually married another alumnus of De La Salle University, Raymart Santiago (of the well-known brood fathered by producer-director Pablo Santiago, preceded in showbiz by his brothers Rowell and Randy).

Which brings us to the latest teapot tempest. The situation could not be more high-profile, with the country’s chief executive, a family friend, attending the wake of the Barretto patriarch. Gretchen and Claudine had patched up their differences, and Gretchen attended ostensibly to reconcile with her mother. A third Barretto showbiz aspirant, Marjorie, who never attained the same level of stardom as her younger sisters, refused President Duterte’s admonition to greet Gretchen, alleging that her niece, Nicole, was traumatized by Gretchen spiriting away a lover, businessman Atong Ang.

In a sensational tell-all TV interview, Marjorie acknowledged that after the collapse of her own marriage to Dennis Padilla (actually Dencio Padilla Jr., son of a late comedian), she bore a love-child to a former mayor of Caloocan City; this was by way of pointing out that Ang was also very much married, and that Gretchen was thereby being unfaithful to Cojuangco, who similarly was married to someone else.

Predictably, Gretchen denied any sexual relation between her and Ang. What conclusions can we draw from the situation? One is that the Barretto sisters are expert enough at making the most of media coverage, notwithstanding the occasional phone-cam recordings of slip-ups like Claudine’s fistfight with Mon Tulfo or the screams and hair-pulling (with the Presidential Security Group atypically befuddled) that occurred during the wake. Marjorie’s subsequent TV interview effectively erased an earlier scandal when her daughter, Julia, admitted boinking hunky star Gerald Anderson, who was supposedly committed to Bea Alonzo. Julia claimed that she had broken up with male starlet Joshua Garcia (just as Anderson’s relationship with Alonzo had ended), but also wound up denying that she was the mistress of another rich elderly man, Ramon Ang.

Another conclusion we can make is that males involved in any capacity in this scenario will be better off quiet. Atong Ang appeared in one of those obviously staged “ambush interviews” coddling his legal family while declaring he had never diddled any of the Barrettos. Assuming he was truth-telling, he was also effectively saying – awkwardly, at that – that some of the Barrettos were lying. Miguel Alvir Barretto, the family patriarch, was better off: even with Gretchen recapitulating her accusation that he had molested her, no one wants to speak ill of the dead.

An even more significant conclusion echoed by social experts looking at the current Barretto flameout, is that the scandal’s staying power derives from what it says about us, more than about the family itself. It’s women claiming for themselves what moral authorities used to say only men were entitled to: the privilege of behaving badly. The scope even has the trigenerational impact of classical Greek tragedy, from parents to children to children’s children.

A fast-declining generation might even remember when a similar phenomenon used to command the attention of the media and public, not just in the Philippines but also overseas: the Marcos family saga, from the patriarch’s womanizing and his wife’s philistine overcompensation, through their rebellious daughter’s romance with an oppositionist scion (including a kidnapping and fall-guy killing that foreshadowed the murder of Benigno Aquino Jr.), to their exile and triumphant return to a country that seemingly has not had enough of their excesses. Thankfully, the worst that the Barrettos can visit on themselves and their public will never be as malevolent as their high-profile media predecessors had been.

Joel David is Professor for Cultural Studies at Inha University in Korea and was the recipient of the 2016 Gawad Lingap Sining (Art Nurturer Prize) of the Filipino Arts & Cinema International Festival in San Francisco, California. He had previously taught at the University of the Philippines Film Institute, where he was founding Director. He holds a PhD in Cinema Studies at New York University and maintains an archival blog titled Ámauteurish! (at https://amauteurish.com), which contains all his out-of-print books and articles on Philippine cinema, media, and culture. His latest books are ‘Manila by Night,’ part of the highly acclaimed Queer Film Classics series of Arsenal Press, as well as the forthcoming ‘Millennial Traversals’ and the Sine list of 100+ outstanding Filipino films.

(C) The FilAm 2019