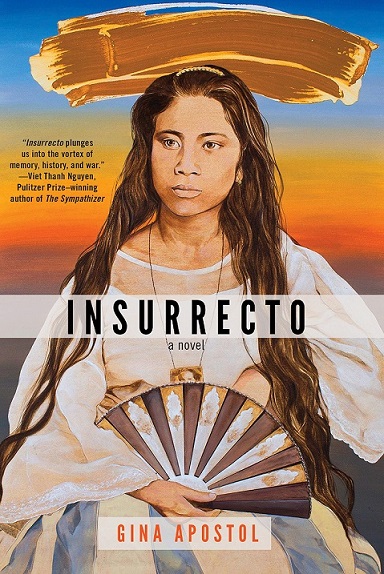

A touch of dry humor in Gina Apostol’s latest novel ‘Insurrecto’

By Eileen R. TabiosGina Apostol’s novel “Insurrecto” started receiving plaudits as soon as it was released, including citation in Publishers’ Weekly’s Best Books of 2018. Praise, the novel does deserve, for its masterful language as it presents a multi-layered and consistently energetic disquisition on a Samar Massacre during the Philippine-American War.

From the 1901 incident in Balangiga, Apostol spirally addresses a multitude of topics and themes through the characters of a U.S.-American filmmaker Chiara Brasi with translator and expatriate (residing in Queens) Filipina writer Magsalin. Both are researching, and competing with each other, as they explore the story of Casiana Nacionales who had strategized the decimation of an occupying American garrison.

Appropriately, critics have noted and will note the novel’s importance—its necessity even—as a rare treatment of a war, The Philippine-American War, that stubbornly has been, to quote Apostol, “unremembered.” But neither do Philippine-American relations—relations, not just that early 20th century war—constrain the novel’s narrative. The novel also ranges over film-making techniques, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, Elvis Presley, colonialism, Pres. Duterte’s rule as well as the natures of art, memory, desire, family, culture-making, and other elements of the human condition.

What has received less critical attention so far—so that I choose to focus on it—is Apostol’s keen sense of humor that is of immense help in harnessing this rambunctious novel into a manageable and then enjoyable read.

Apostol’s humor helps in characterization. For instance, in describing the character Ludo, his wife Virginie at one point observes that Ludo “is still thinking, a terrible condition”—an observation that makes the reader pause to laugh as one considers the implication of a person’s “thinking” as being a “terrible condition.” It’s the type of phrasing that generates readerly affection for its many applications beyond the novel’s narrative (including in a reader’s own life).

Apostol’s humor also sources wonderful metaphors. For instance, this sentence that takes place in a house bearing soaked carpets from a rain: “An obscene dead cockroach, its genitalia splayed out for the world to see, is coming and going in waves, like an upturned boat with frail masts.” Not only is that sentence picturesque but it’s grin-cracking droll.

Similarly, Apostol’s humor enlivens her similes. For instance, the second reference in the phrase “as ordinary as stirring coffee or scratching an armpit.” The latter’s slyness brings in a welcome impishness to a scene describing a white celebrity filmmaker maneuvering through Manila.

Apostol’s humor, perhaps despite itself, even occasionally becomes poetry: “Emotion will lie in the film’s structure, like a silent grenade.”

Apostol can even elicit a laugh over something that may or may not be understood by a reader. For instance, this phrase: “dwarves in space (a physicist’s dream).” I’m no physicist so I don’t necessarily understand that phrase, yet it makes me laugh.

Apostol’s humor bears that element that maximizes the funny: dryness. Here’s an example about one of the protagonist’s ways of conducting research, which should be appreciated by all of us netizens:

“After clicking on all the Balangiga items in her Google search, as far as page 102, Chiara says she cheated and began a new search. She finds fifty-seven articles by an Iranian journalist named Samar, and twenty more by her Jordanian counterpart also named Samar, before she narrows her search to ‘Balangiga Samar 1901.’ It is embarrassing to note Chiara’s unscholarly search habits but I imagine no one is unfamiliar with her process.”

One of the most effective ways to enhance the effect of a joke or a witty remark is to underpin it with deep thoughtfulness; multiple layers of significance elongates resonance—it can make unforgettable a joke or other manifestation of humor. Apostol’s humor is so smart it seamlessly and often transitions to meta. For instance, “he laughs as if he has invented the act that will follow and that, soon enough, swallows him.” That’s a statement that can linger or come up unexpectedly as a recall, given its penetration as an observation.

“Insurrecto’s” story is wide-ranging, thus, contains many dark elements because such is the 20th-21st century history of the Philippines. Apostol’s sense of humor helps us bear the darker aspects even as it highlights the darkness of such aspects, from colonizing wars to contemporary horrors ranging over incompetent bureaucrats wreaking havoc on Manila’s traffic or extrajudicial killings. Apostol clearly conducted her research well; one can discern that her own sense of humor was helpful for processing discoveries that led to this novel. It’s unfortunate that humor, while helping us to bear negative situations, doesn’t necessarily translate to solutions for such situations. Thus, “Insurrecto’s” story ends in song, and (or, but) it is karaoke.

Eileen R. Tabios has released over 50 collections of poetry, fiction, essays, and experimental biographies from publishers in nine countries and cyberspace. More information about her work is at http://eileenrtabios.com.

© The FilAm 2019