The bells of Balangiga: The politics and quiet diplomacy behind their long journey home Part 1

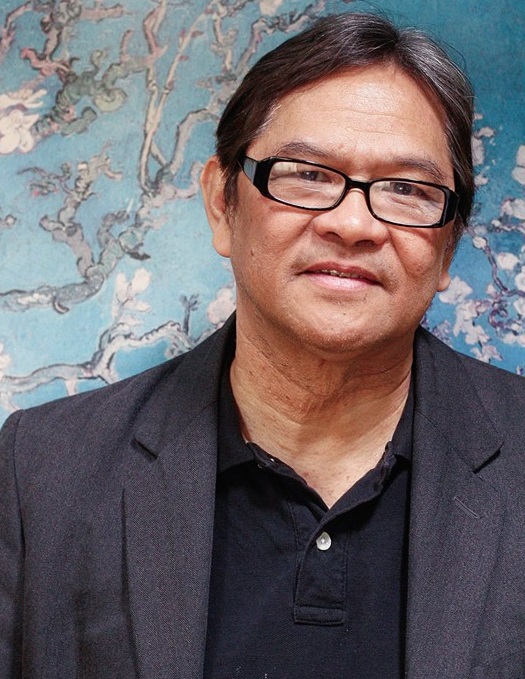

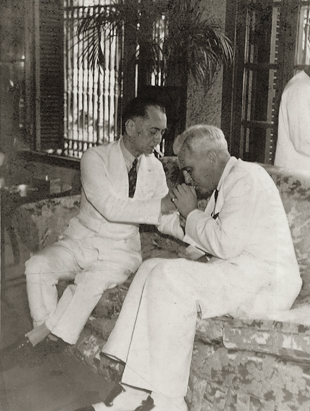

The author, who was U.S. Special Envoy of the Diocese of Borongan, and Joe Sestak, Wyoming Veterans Commissioner met for the first time at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming in 2004. Photos courtesy of R Sonny Sampayan

U.S. Air Force veteran, R Sonny Sampayan-Sampayan spent 21 years working on the return of the bells of Balangiga. The journey of the bells lasted 117 years. A grand-nephew of noted novelist Carlos Bulosan, he was born in Binalonan, Pangasinan and migrated to California at the age of 10 in 1969. Below is his account of the three bells’ long journey home.

By R Sonny Sampayan, as told to The FilAm

It began as a personal pursuit in 1997.

I was still on active duty assigned to Ramstein AB, Germany, when during Commander’s Call, my commander told all of us that we were the unofficial ambassadors of the United States and that we should try to improve relations with our allies. I thought, hmm.

I was travelling to the Philippines to find out who Edith Sampayan — who was to become my wife — was. I was curious because we share the same surname. I’ve seen her name on credits of several ABS-CBN programs. Upon arrival in San Francisco en route back to Germany, I picked up a copy of Philippine News and read about the plight of World war II veterans and the Balangiga bells.

I began to spend long hours in the Ramstein library researching the story of the 1901 Balangiga Incident in Samar. The incident would take on two related narratives: The brutal killings of nearly 50 American soldiers at the hands of Filipino guerrillas — some dressed in women’s clothing — and the killings by U.S. retaliatory forces against thousands of Filipino villagers. Filipino guerrillas fleeing Balangiga burned the village and the U.S. forces also torched Samar when General Jacob Smith ordered his men to “turn Samar into a howling wilderness.” As a result, religious artifacts, including church bells, were found on the ground. U.S. forces brought them back as war trophies and also to prevent Filipino guerillas from melting them for ammunitions. This is a common practice during wars.

Private Adolph Gamlin and other survivors went back to Balangiga after the massacre to bury their comrades. He drew a map of the village and identified landmarks and locations where all the Filipino and Americans were buried. His daughter, Jean Wall, who was with us during our research, kept that map and shared it with us.

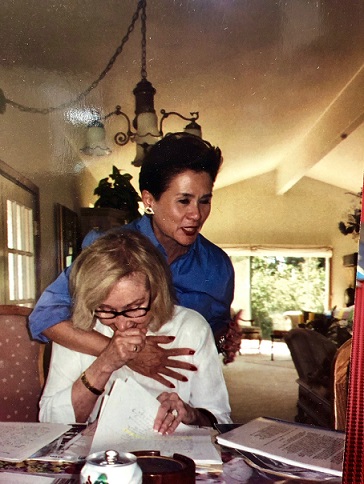

Yolanda Stern and Jean Wall, who was overcome with emotion as she recalled the story of Balangiga her father had shared with her, were part of the team that lobbied for the return of the bells. Wall’s father had survived the attacks.

Return one bell, keep the other

Something curious happened around 1998. Then Philippine Ambassador Raul Rabe visited Wyoming and spoke with Wyoming veterans who were adamant about keeping the two bells at the F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne. (The third bell is in Korea.) He showed the documentary, “Savage Acts: Wars, Fairs and Empire,” produced by the American Social History Project of the City University of New York to the veterans. The film about America’s campaign of expansionism, with a narrative on the Philippine-American war from 1989 to 1902, did not sit well with the veterans. Before the documentary was shown, the veterans had supported returning one bell and keeping the other one. The return of one bell did not happen.

Quiet years

Nothing was heard for several years, although quiet diplomacy continued away from the attention of the public and the media. I met with several individuals who would join the Balangiga Bells crusade.

I came to know Erwin “Swede” Huelsewede, another U.S. Air Force man, who would become a special assistant and senior adviser to Secretary of Veterans Affairs Anthony Principi in 2002. Swede became fascinated by the story of the bells which he often heard from me.

In 2002, Swede and I reached out to California philanthropist Dr. Tom Stern, his Filipina wife Yolanda Ortega Stern, and Maria Lazaro-Elemos, a registered nurse who helped in the lobby effort. Our small group met in the Sterns’ home in Napa. We were joined by Jean Wall, the daughter of Army Private Adolph Gamlin who survived the Balangiga attack. She briefed the group on the history of Balangiga.

The ‘Bible on Balangiga’

I hated her guts in the very beginning then I began to understand her. We became wonderful friends despite long heated debates over the phone and e-mails. She wanted to educate researchers on the true story of Balangiga. She also wanted to clear the name of her father and Company C, 9th Infantry; many of the soldiers died in the attack. I’ve visited Jean and saw original letters in her possession. Jean is the “bible on Balangiga.” Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

In 2003, then-Archbishop Orlando Quevedo of Cotabato and Bishop Leonardo Medroso of Borongan asked the Vatican to intervene. The Apostolic Nunciature endorsed their request – contained in endorsement letter #20.901 — “to have the bells of Balangiga returned to the Church to which they originally belonged.” That request fell on deaf ears. Vice President Cheney is from Wyoming.

In 2004, Swede and I traveled to Wyoming for the very first time. We were shocked and angered when we saw the Balangiga church bells. I thought the bells belong in the church not on a parade ground. We met the 12 Wyoming Veterans Commissioners (WVC) and pleaded that the church bells be returned. The WVC appointed Joe Sestak as the committee chair to look into the Balangiga bells issue.

Sestak became an important figure in the return. He was at the forefront of the campaign to keep the bells in Wyoming in 1998. They have been there since 1904 or two years after the end of the Philippine-American war.

NEXT: Credit goes to the U.S., Philippine secretaries of Defense