Once, my life intersected with V.C. Igarta

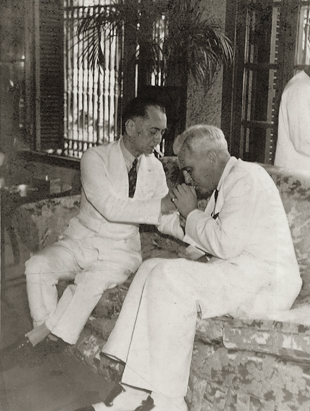

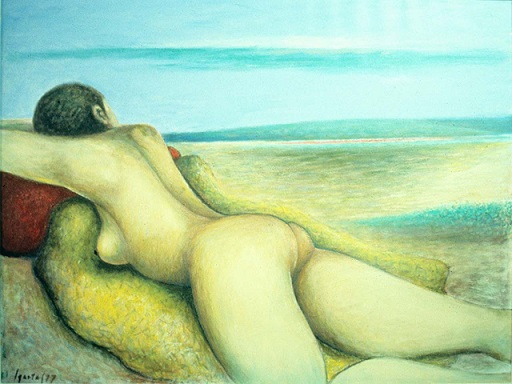

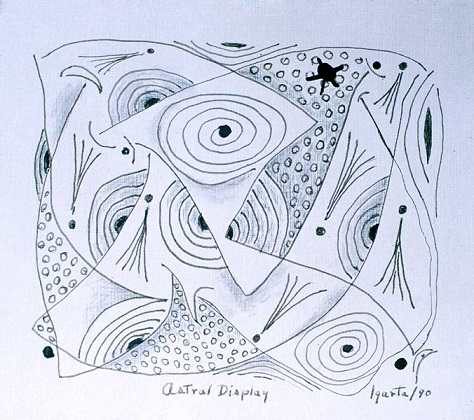

By Eileen R. TabiosIn my last few years living in New York City — before moving to San Francisco about 18 years ago — I spent time with Venancio C. “V.C.” Igarta, the foremost artist of the Manong generation. By the time I met him through an introduction by poet Luis Cabalquinto, he had enjoyed success as an artist as well as received praise as a master colorist.

But attention is fickle in the arts and by the time I met him, accolades had receded from the general art world and came mostly from Filipino and Asian American communities. Such ebbing for attention made Igarta—as it would with most artists in that situation—question the long-term fate of his art works. When we met, he was in his 80s and receiving treatment on a dialysis machine which must have also forced him to confront his mortality. These elements made him a fragile and moving figure to me by the time we met.

But one of the great regrets of my life is that I wasn’t strong enough to weather Igarta’s fragility. Perhaps it was because I was just starting out as a poet and his discernible concern about his art hit too close to the bone. I was/am a self-made poet and it was disconcerting to see a master artist question his fate when I was just starting out in my own art and figuring it out on my own. Nor did it help that, as a younger poet, I was quite fraught. With hindsight, I may not have wanted to think that years of commitment to an art could result in being ignored (though, as a more mature poet, obscurity is actually fine with me as I now understand that the point of art-making and poetry is not fame).

Or perhaps I was initially cool to Igarta because I suspected his appreciation of our shared Ilokano-ness. Unfairly, I considered our shared origin (Ilocos Sur) mostly coincidence—I required time to recognize how much I appreciate and mutually share with Igarta those elements associated with the Ilokano, including a strong work ethic as well as hard-headedness.

Igarta arrived from the Philippines at age 18 in Stockton, California and worked as a farmhand and janitor during the Great Depression years. But he always kept in mind his sister’s charge to him: “Don’t ever beg.” I can’t overstate how much I admire his industriousness, his character.

But while I did not yet fully appreciate him during my New York years, I hovered around him—truthfully, because I hovered around Cabalquinto whose poetry I love and Cabalquinto kept company with Igarta. Igarta, though, seemed more interested in me—he would come to ask to paint my portrait and I agreed. Such enabled more time spent together. We discussed art, art, and art—I always smile when I recall how he loathed that I admire Clyfford Still and gave me a Still monograph that he was happy to kick out of his studio. And we ate a lot of Chinese food together and with other friends. I didn’t appreciate those experiences at the time they occurred, even as they make it impossible now for me to forget that, once, my life intersected with Igarta.

In 1999, I moved from New York to California. During my first year as a San Francisco resident, I returned frequently to New York. I often thought about visiting Igarta but kept thinking “next time.” Unfortunately for me who shall forever be ashamed for my deferred visits, in 2000 Igarta died at age 89. Perhaps someday I’ll cease asking why I could not realize the depth of my admiration and love for Igarta until after he died.

Since Igarta passed, I’ve tried (albeit haphazardly) to spread the word about his art even as each effort is a reminder that it came too late for Igarta—that I failed to show him in time that he and his art mattered/matters to me.

At times, I try to make myself feel better that this is my role—not to be one of those who surrounded him with support, praise, or good humor (I was so young and raw and my humor was incompetent), but to be the one continuing to tell others about him and his art long after his death. In 2001, I wrote about him in a (probably over-the-top) article entitled “Meditations on Ilokano Abstractions” for Our Own Voice, a journal for Filipinos in the diaspora. In 2005, I made sure to include one of his paintings in the landmark exhibition “Poetry and Its Arts: Bay Area Interactions, 1954-2004” presented by the San Francisco Poetry Center at the California Historical Society in San Francisco. In June 2017 I encouraged his inclusion in the Filipino American Artist Directory, an initiative founded by Missouri-based artist Janna Añonuevo Langholz; he will be part of The Directory’s 2018 Edition.

Igarta told me more than once—sometimes with resignation, but mostly with matter-of-fact astuteness — “If I am going to be remembered, it will be by Filipinos.”

The FilAm’s readers can search for Igarta on the internet (including this link of his lovely “FREEDOM!” work in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In fact, Igarta would be a good topic for a documentarian/movie-maker, an idea that surfaced as I recently was interviewed for a documentary on Jose Garcia Villa. A filmmaker would do well to consider Igarta, and perhaps do it soon while those who knew him best are still around (including Cabalquinto, president of the VC Igarta Foundation through which Igarta continues his philanthropic activities posthumously with a legacy that gives grants to artists and art-projects).

Let us not forget. Let us remember Venancio C. Igarta. He was a Manong, which makes him us. He was a great artist, which makes us proud to share with him in being Filipino.

Eileen R. Tabios has released over 50 collections of poetry, fiction, essays, and experimental biographies from publishers in nine countries and cyberspace. Her 2017 books include “The Opposite of Claustrophobia” (Knives, Forks and Spoons Press, U.K.); “Manhattan: An Archaeology” (Paloma Press, U.S.A.); and “Love in a Time of Belligerence” (Editions du Cygne, France). More information is available at http://eileenrtabios.com.

© The FilAm 2017