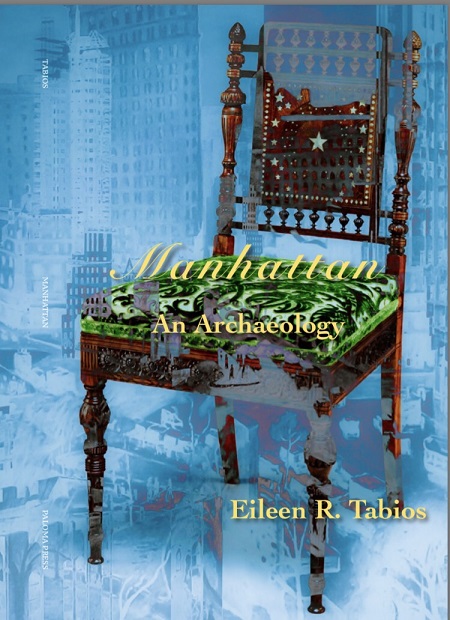

Digging, finding the gems in Eileen Tabios’ collection of poetry

By T. C. Marshall

Eileen R. Tabios’ prolific flow of books has presented all kinds of gems and demonstrated an ability to write from many angles, often within one collection. This book purports to be “An Archaeology” of or about “Manhattan.” That’s a new angle for her, and in her typical way she does archaeology newly. Here, we “dig” the multiplicity of persons and perceptions within “Eileen R. Tabios” and how they unfold into thoughts and feelings among the multiplicities of the city.

The first two-thirds of the book elaborate multiple readings from a one-page prefacing poem called “The Artifacts.” Its core images provide the impetus for long poems and a “novella-in-verse” made of 11 “chapter” poems. They are followed by “vacation” poems on “Skiing away from Manhattan.” This serious framework of proliferations provides a strong sense of constructedness—a structure actually evoking Legos. The poems are solid, and yet their parts are moveable. We dig into feelings and their origins here in an archaeology that constructs or re-constructs a past and, as in Charles Olson’s “archaeology of morning,” a possible future of a city of possibilities.

In “Post-Nostalgia,” the concept of interactions through language helps define this city with “Will you articulate back / to me to teach me / the vocabulary I lose as I speak it?” That loss and recovery are the aesthetic core, as is San Juan de la Cruz’s epigraph: “Vivo sin vivir en mi / I live without inhabiting myself.” Lest that be another old Rimbaud bit re-hashed, Tabios works it fully as she links with many autres. No poem is cut short; thought carries them on beyond succinctness. Worlds are elaborated from the boundary where irrealities meet the real: “while the air, too, begins / to become physical // by taking on the tinge / of fire, rose, ruby, / sunset, dawn, sunset …”. The images for all the senses are strong, but they also cross back and forth over that line between thought and image. That is the thrust of this book.

The “Clyfford Still Studies” exemplify this poetics. They are linked to the whole book by the mention in “The Artifacts” of a “monograph on Still’s paintings,” but these poems take the book to its full pitch of intensity. Beyond Joan Mitchell’s excitingly abstract dogs or trees, Still’s paintings provide a dance or frieze of abstracted shapes without thing-ly referents. They have a “feel” to them, and that’s where the essayistic poems start and often end. Tabios’ poems both rivet and ramble in a purposeful manner, moving into thinking as it arises from and with feelings. Still’s greatly abstract work are imagistic without being referential. Tabios followed in that direction—Still’s great strength—with their play beyond imagery. The poems “correspond with” the paintings, much in the manner of a Jack Spicer translation. The poems are not deictic, and yet they read the paintings in a way that respects their abstractions. They are anti-deictic by ranging widely from their impetus and freely including multiplicities of thought, image and feeling.

The titles for each of the 18 “Clyfford Still Studies” begin with “On.” “On the Inescapability of Fragility” concludes with the word “Fragile.” Many other words might have arisen from this large painting (105 X 92 1/2 inches)—a field of black with a few jagged rips of color. Tabios’ choice to let the poem move from “If you would only consider the effects of humiliation from the existence of teeth” to “as if we are not all Fragile” is brilliant. The poetic logic may linger around the fragility of teeth, but along its way this poem meditates on gender and family and identity in ways that are hardly abstract. These poems engage the paintings in a chat.

“On The Delusion Called ‘Relief’” begins with a spider who’s still alive after a squishing attempt. The interpretation may come from the non-figurative figures of black with light highlights floating in a field of deep red. These “figures” are almost disembodied; the only “things” they truly resemble might be something like galaxies, but they become “beings” in Tabios’ poem. The poem concludes “for certain creatures that wander throughout this vast universe / illusions are limited—there is no Relief.” That’s the “essay” quality: these poems think. They push beyond the accepted aesthetic of image and feeling into questioning how our thoughts arise.

“On Obviating the Mundane” works its way from images of a bare back to the philosophical conclusion that “nothing is Mundane.” In these poems, nothing is merely mundane because everything can be read through the complex of thoughts and feelings delivered. Tabios’ readings make Still’s great paintings richer, even without our looking at them. That’s an accomplishment—and a new and large accomplishment, even in the vast bibliography of Eileen R. Tabios.

T.C. Marshall lives and works in the coastal mountains of California, darting out like a dragonfly into poetry scenes here and there. Recently, he delivered a paper on “Post-Crisis Poetics” at Buffalo’s big conference on what’s coming up in “the next 25 years” and had another published in Brian Ang’s online anthology exploring that topic. Dr. Marshall teaches college composition to keep his feet on the ground and communes with nature to keep his head in the air. Cities feed his energies, too, as he studies the works of advancing artists of all kinds who help inform what poetry can do.

(C) 2017 The FilAm